This is the fourth in a series of articles reported in Northwest Georgia, an area rich in stories about unmet health needs and about people and programs making a difference. Georgia Health News and the health and medical journalism graduate program at UGA Grady College of Journalism and Mass Communication collaborated to produce this series, made possible by support from the Healthcare Georgia Foundation and the Institute of International Education.

Pickens County High School is a sprawling campus on the outskirts of Jasper, the largest town in the county. It’s located east of I-75, roughly halfway between Atlanta and Chattanooga.

The buildings are modern and include dance studios as well as livestock barns, increasing the likelihood that students from across the area will find something to be passionate about.

The school offers another valuable resource to students, whether they aspire to careers in agriculture or the arts. Any of them can go see the school nurse.

Students in other schools may not be so lucky. Schools and other venues don’t always have nurses.

“It’s not news to anybody that there is a nursing shortage,” said Kimberly Parker, the nurse at Pickens County High School. “We need more nurses. We . . . need educated, professional, committed nurses.”

Last year at this time, 73,330 Registered Nurses were practicing in Georgia, according to an official federal tally. Based on population size, that’s not nearly enough to fill the state’s needs. The Georgia Nurses Association says there could be a shortage of 50,000 RNs by 2030.

The current nursing shortage is one of the most significant to hit the state, and it continues to worsen. (Here’s a recent article on the shortage.)

According to the Georgia Nurses Association, more than 50 percent of the nursing workforce is nearing retirement age. Meanwhile, the aging of the population as a whole means that more nurses and health professionals are needed to act as caregivers.

[youtube]https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=19zdWfRAImk&feature=youtube[/youtube]In the Northwest Georgia mountains, Blue Ridge Area Health Education Center (AHEC) is scrambling to relieve the nursing shortage.

Blue Ridge AHEC is a nonprofit regional health education center based in Rome, charged with increasing the supply, distribution and education of health professionals within the 20-county region they cover. Georgia is divided into six AHEC regions, and all are making similar efforts.

Kristie Washington coordinates the RN re-entry program, based in Rome. It helps people who formerly worked as nurses re-qualify and get back on the job. Twenty-two nurses have completed training since it began in 2009, and 20 of them are practicing in the Blue Ridge area now.

The program will probably never be huge, but it’s ideal for the small number of people who need it, said Washington, who went through the program herself. Since Washington took over the program in July, nine participating nurses have regained their licenses.

The program helps two types of formerly active nurses: those who have been licensed to practice in another state but not in Georgia; and those who once had Georgia nursing credentials but whose licenses lapsed or expired.

The Georgia Board of Nursing requires nurses, among their other qualifications, to maintain proficiency by practicing the profession for a certain number of hours within a defined period. If they work less than the required number of hours, their licenses expire.

AHEC runs refresher programs that help nurses regain their licenses. Nurses complete 40 hours of didactic self-study — using resources such as manuals and online material. Then they are matched with a preceptor and placed for 160 hours of supervised nursing practice. Once those requirements are met, the nurse can get a new license.

Established practitioners, such as school nurse Parker, are the preceptors who guide participants through the clinical part of the program.

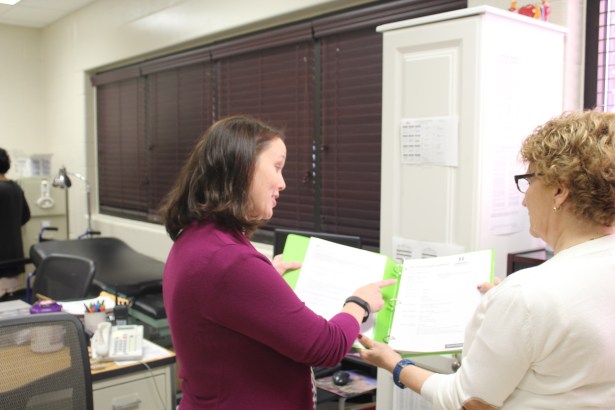

Parker has supervised nursing students before, but Deborah Smith is the first re-entry RN she’s worked with.

Smith worked in orthopedics and in medical surgical settings, then went back to graduate school and became a manager. She practiced in Pennsylvania and then in Georgia before stepping back from bedside nursing about 15 years ago, to focus on more managerial roles.

She kept her Georgia license current until there was a mix-up with her renewal.

Smith is excited about regaining her Georgia nursing credentials, but is also feeling just a little sleepy lately, as she adjusts to her new hours.

“I’m tired, because I have to get up at 6:15 in the morning and I haven’t had to do that in a really long time, but I really like it,” said Smith, “I’m also somewhat nervous.”

Parker, who supervises Smith at Pickens County High School, says “precepting and raising the bar for professionalism for nurses in every field is something that’s incredibly important to me. It’s why I’ve been so involved in education and students and professional development for pretty much the whole time I’ve been a nurse.”

Parker and Washington, who runs the AHEC re-entry program, believe that it’s crucial to have training in a variety of settings.

Judging from television dramas, one would think that nurses practice only in large urban hospitals. In real life, things are different. And in Georgia’s rural areas, nurses are just as likely to be found caring for patients in county health departments or on public school campuses.

In places like Blue Ridge, for instance, numerous nursing jobs are not in hospitals. “We have our hospital, a few private practice offices and the school system,” said Parker.

Regardless of what setting in which they practice, nurses have to keep up with the times. Diagnostic and monitoring technologies have changed enormously since Smith last treated patients, but she’s getting up to speed by working with Parker.

“We were laughing about the blood glucose machine the other day,” said Parker, “now they are so concise and everything’s built in, but it used to be this big huge monitor!”

As a preceptor, she helps re-entry nurses get comfortable with new machines and new practice guidelines. She’s also a role model: Smith, who always wanted to work in children’s medicine, hopes to stay in a school nursing job once she regains her license.

In addition to AHEC’s six regional programs, two metro Atlanta universities — Kennesaw State and Clayton State — also have programs aimed at putting nurses back into the workforce. But for people who live in Northwest Georgia, “there’s only really one place up in this part of the world,” said Smith, who lives in Pickens County. The Blue Ridge AHEC is it.

Nurses who have completed the re-entry program have no trouble finding work. Eight of nine nurses who’ve graduated from the Blue Ridge AHEC program since July 2016 have jobs, the other is not actively seeking a position at this time.

“So far, the job placement rate has been excellent, and all the jobs are within our 20-country region of Northwest Georgia, except one who is working in Hall County,” said Washington. “I have another candidate who hasn’t even finished the clinical portion of the program yet and already has a job offer.”

Parker, the school nurse and preceptor in Pickens County, is a believer in what AHEC does.

“From my perspective,” said Parker, “anywhere that you go, if you have nurses that took the time to go to nursing school and paid the money to go to nursing school and took off for whatever reason and want to come back into the nursing field, then they need this program.”

Naomi Thomas is a graduate student at UGA pursuing a master’s degree and career in Journalism. She received her undergraduate degree in Media, Communication and Cultures from Leeds Metropolitan University and has an interest in health workforce stories. Her twitter handle is @nrthomas123.