GHN Special Report on Child Cancer: Part One

Jointly reported by WebMD and Georgia Health News

Fourteen-year-old Lexi Crawford was attacked by lower back pain so sharp that she couldn’t even sit up to eat. Her mother had to bring her food while she was lying flat on her back. Doctors in Waycross, GA, the town where she lives, thought it was a kidney infection. But after months of antibiotics didn’t clear it up, a visiting doctor in the local ER suggested an X-ray.

[youtube]https://youtu.be/mCizhUiDZnw[/youtube]What he saw on the scan was terrifying.

Black spots covered Lexi’s spine. “That’s cancer,” he told her mother, Cristy Rice. “I don’t know what kind it is, or where else it is, but that’s cancer.”

As Lexi first started feeling sick, in a house across town, 2-year-old Harris Lott began complaining that his stomach hurt. He suddenly lost the ability to urinate, and his parents, who are both doctors, rushed him to an emergency room. He was diagnosed with an infection. After treatment, he was fine for a while, but a few weeks later, the problem returned, and a urologist said it was time for more tests. They found a tumor the size of a grapefruit in his abdomen.

A few days later, doctors told the grandparents of 5-year-old Gage Walker, who lives 14 miles east in nearby Hoboken, GA, that the unrelenting stomach pain he’d had for weeks was probably constipation. For 2 months, doctors sent him home with laxatives. “He would just cry and cry and cry. I thought something was really wrong,’” says his grandmother, Ellen Walker. It, too, turned out to be cancer.

The same cancer.

All three kids were facing a common enemy: a soft-tissue cancer called rhabdomyosarcoma.

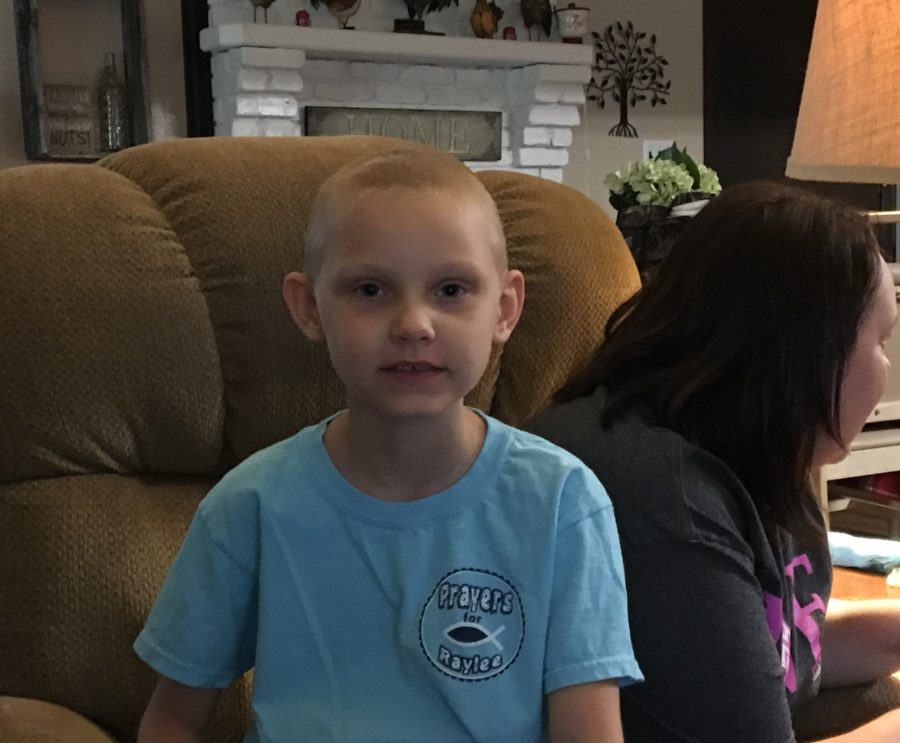

It’s rare. Only about 350 cases of rhabdomyosarcoma are diagnosed in the U.S. each year. Even more puzzling, at about the same time, another child in the area, 5-year-old Raylee Metts, was diagnosed with a related but even rarer cancer, Ewing’s sarcoma. There are about 250 cases of Ewing’s in the U.S. annually.

All told, within 60 days in 2015, four children with rare sarcoma cancers were being treated with intensive chemotherapy, fighting for their lives, family members said.

In the southeast Georgia community where the children live in and around, some suspected it was more than just a coincidence. But in trying to prove that, worried residents didn’t know they would be facing obstacles nearly as formidable as the cancer itself.

A history of pollution

Lexi’s house sits on the corner of Hamilton and Brunel streets in Waycross, a town of about 15,000 people. Drive east on Hamilton, and within a block, you’ll see rusty pipes sticking up out of the ground like straws. These are monitoring wells, and they are planted in empty fields that border Hamilton Street behind a chain-link fence.

Railroad company CSX Transportation owns the fields — part of the sprawling Rice Yard complex in the center of town — and the 755 acres beyond them.

The wells have been there since the early 1990s to monitor an enormous spill, or plume, of toxic chemicals that has been moving underground for decades.

State environmental inspectors first ordered the site to be cleaned up in 1985, when they found a stew of hazardous chemicals that were being handled carelessly. Paint strippers were poured into shallow pits. Solvents were poured down floor drains.

The state Environmental Protection Division (EPD) ordered the railroad to find out exactly how much hazardous waste it was generating and where it was going. They fined Seaboard System Railroad, then the owner, $30,500.

When the state returned for a follow-up inspection a few months later, they caught workers dumping toxic waste onto the ground in an area of the property that sits near Lexi’s neighborhood.

A few months later, the company received a second fine of $50,000 when inspectors found workers dumping toxic waste onto the ground near Lexi’s neighborhood. Inspectors who tested the waste found high levels of volatile organic compounds including cancer causing trichloroethylene (TCE), and methylene chloride, a paint stripper that is thought to cause cancer.

The state issued a second fine to the railroad for $50,000, and required it to establish plans to monitor the pollution and clean it up.

Although the company has pumped and treated more than a half-billion gallons of water from the ground since 1993, recent tests from the monitoring wells continue to show that significant levels of contamination remain underground. Part of the issue may be that CSX is using a technique that the EPA cautions doesn’t work well to clean up these types of chemicals. As recently as last year, CSX got permission from the state to add a third well to help treat the toxic water.

In a statement emailed to WebMD, CSX said the data they’ve collected show their system is “effectively capturing and treating the impacted groundwater. The safety and health of the public and our employees is CSX’s first priority in all aspects of our operations.”

CSX says the chemicals that were spilled there have never left its property. But there’s been little testing from the state or the company to check that. CSX did not respond to specific questions about how the company knows that toxic chemicals haven’t leached off-site.

Residents and environmental experts question whether that is true.

A community group called Silent Disaster, led by former Waycross resident Joan Tibor, has been tracking the cases of childhood cancer in the town. For 3 years, the group has prodded authorities to investigate whether the town has a cancer cluster.

She alerted state Rep. Jason Spencer, a Republican from Woodbine, who is also a physician assistant. He says the news of the children’s cancers got his attention. He also started pushing the Georgia Department of Public Health to do more to help the town.

The department repeatedly denied interview requests for this story. All information in the story is from public documents that are online or received through open records requests from WebMD and Georgia Health News.

Last December, the federal Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR), a division of the CDC, agreed to help. They are overseeing state health officials as they try to determine if the chemicals spilled under CSX threaten the health of the community. Their report on CSX is finished, and according to an update sent to Spencer, is expected to be posted for public comment by the end of the year.

ATSDR has also agreed to supervise state efforts to look into possible health risks for a second contaminated site: The old Consumers Gas and Coke Company. Between 1916 and 1953, the plant, which is now owned by the Atlanta Gas Light Company, turned coal into gas to heat and light area homes. The process created toxic coal tar, spiked with chemicals like arsenic and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), both linked to cancer. In the early days of the company, this sticky coal tar was dumped into a canal that runs through downtown neighborhoods and a public park. Atlanta Gas Light eventually removed more than 128,000 tons of contaminated soil from the canal and continues to monitor the site, but the cleanup wasn’t started until the late 1990s, more than four decades after the plant shut down.

The two companies aren’t the town’s only worry.

Waycross has two other active state Superfund sites — polluted sites in need of cleanup — and four other area businesses have recently been cited for violations of federal environmental laws. The EPA determined that another old state Superfund site, Seven Out Tank, a facility that took in hazardous wastes but failed to properly treat or dispose of it, had toxic chemicals at levels that increase health risks. But follow-up reports from the EPA and the Georgia Department of Public Health said that people probably weren’t being exposed to them in ways that would harm them. Some residents worry that all the dumping, spills, and releases over the years have poisoned their town.

When they were interviewed for this story, Haylee Metts, her husband, Ray, and their two young children lived in a trailer about 20 minutes southwest of downtown in the small community of Manor.

Standing at the end of her driveway, she points down the street. “Starting at my house, there are six houses. Every house, starting with my house, has some form of cancer,” she says.

In her house, cancer hit her 6-year-old daughter, Raylee. She was diagnosed with Ewing’s sarcoma, an aggressive bone cancer that spread to her rib, spine, pelvis, shoulder and hip before doctors figured out what was causing her symptoms.

Raylee spent a year in intensive chemotherapy at Wolfson Children’s Hospital in Jacksonville, FL, where many kids in southeast Georgia are treated.

Haylee Metts said she had never wondered about chemicals in the area until she started talking to the nurses at the hospital.

“The nurses one time — and they said they were joking — said, ‘What’s in your water there? We have so many cases from your area that come in here, it’s unreal,’ ” Metts said.

“It sends red flags to me,” she said, “Why? What’s causing it?”

After Raylee was diagnosed, her family stopped drinking their well water. They’ve since moved to get away from a small farm next door that regularly sprays pesticides on its crops. Haylee says they felt they had to relocate to protect their son, Kreek, who is a toddler.

Desperate parents seek answers

Lexi Crawford’s mother has pin-sharp memories of the horrors of the last year’s fight against rhabdomyosarcoma, a cancer that springs from the soft tissues of the body. Doctors believe Lexi’s cancer started in the muscles of her upper thigh and quickly spread.

By the time she was finally diagnosed, her medical records show how completely the disease had engulfed her body.

The cancer was in at least six different places; it had taken over 95% of her bone marrow. Her lungs had so many half-inch spots of cancer that doctors wrote they were “too numerous to count.”

She was classified as stage IV, grade 4. The worst of the worst.

For a while, Lexi was getting powerful chemotherapy drugs in her veins to poison the cancer five days a week. It made her very sick.

Her mom, Cristy Rice, remembers hearing popping sounds as Lexi bent over the toilet to retch. The pops were bones breaking in Lexi’s back.

For the most part, Lexi, an honors student, has borne these agonies without question.

But Rice says that on a couple of nights, when Lexi has been startled out of sleep by a deep, stirring panic, she has sought the comfort of her mother’s arms and asked, “Why me? I’m a good girl, and I get good grades.”

“What do you say to that?” Rice says, throwing up her hands. “I told her ‘I don’t know, but I want to know.’ ”

“They’ve been able to tell us they don’t think that it is genetic. It’s nothing I did or her father did,” Rice says. “But they can’t rule out environmental causes.”

Poisoned places struggle to get attention

Every year, hundreds of communities across the U.S. find themselves in the same place as Waycross — worried and full of questions. Almost none get answers.

Surveys of state health departments have estimated that they get between 1,000 and 2,000 reports of clustered illnesses — typically cancer — every year.

There is no national system for tracking the fates of these reports, so a 2012 study tried to figure out what happened to them.

Looking over a span of 20 years, Emory University researchers found 567 cluster investigations. Only 72 of those were confirmed to be clusters, meaning that there actually was more cancer in a given area at a given time than would have been expected.

Just three were associated with environmental factors. In Charleston, SC, an investigation found many cancer patients had been exposed to asbestos when they worked at the naval shipyard there. Childhood leukemia was linked to TCE-contaminated water in Woburn, MA. Brain cancers and leukemia in children were linked to volatile organic compounds (VOCs) in drinking water in Toms River, NJ.

Digging for answers

Tibor, the former Waycross resident who is pushing for help, once owned a business in Waycross. But in 2012, she started getting sick with a puzzling collection of symptoms — breathing problems, headaches, ringing in her ears, mouth sores, and blood pressure that would drop suddenly. Those were followed by more problems. One morning, she woke up to find she could hardly see out of her right eye. She lost 30 pounds while gobbling food. Benign tumors grew in her leg and thyroid.

After consulting dozens of doctors, she says the only explanation anyone could give her was that something in her environment was making her sick.

“My doctor told me that if I didn’t move, I was going to die,” she says.

So she packed up her things and moved in with her son in Florida. She also spent 2 months getting medical treatment from an environmental health specialist in South Carolina. It helped, but she still falls ill when she returns to town, something she doesn’t do very often.

Now she works almost full time digging into reports, looking at testing records, and writing emails and letters to state and federal agencies. She also runs several Facebook pages.

In 2013, Tibor began collecting stories of other sick people in Waycross and plotting them on a map. With nothing obvious to connect the cases, she has pushed the state to do more testing around contaminated sites and the homes of sick residents.

Help has been slow in coming. So far, based on the minimal testing that’s been done, no one can say if the chemicals in Waycross have affected people. There’s no clear connection between the cancer cases. Two of the kids with rhabdomyosarcoma drink the city’s water. The other uses a private well. They’re not in the same neighborhood. They live varying distances from the sites of known pollution.

The Lotts, the doctors whose son, Harris, is one of the three children with rhabdomyosarcoma, say that they have not been given evidence so far that links the child cancers to the Waycross environment.

Public health officials are still trying to determine if their cases represent an unusual increase. In an initial report on the cancer cluster, they’ve said the cases involve too many different types of cancer and are spread too far apart to be related. They won’t know for sure until the state’s cancer registry has been fully updated, which could take 2 more years.

Spencer, the Georgia state representative, doesn’t agree with the report’s early findings but says he isn’t surprised. He wants health officials to consider the whole region as they count the cancers.

“I had a feeling they would dismiss it quickly. It is a big deal to declare a cancer cluster,” he says.

Disagreement about dealing with the problem

Not everyone welcomes Tibor’s efforts to show that environmental contamination is making people sick. Some feel like families going through horrible personal tragedies are being harmed a second time by wild speculation and rumors.

“I don’t think that everybody understands the emotion and the basic hell that these families are going through,” says Gigi Goble, who helps run a local nonprofit called Mattie’s Mission.

Mattie’s Mission is named for Goble’s niece, who died 2 years ago at age 6 from a rare and inoperable brain tumor. Most of the children whom the faith-based organization helps live in the Ruskin Elementary School district, which includes nearly all the CSX property and some surrounding neighborhoods.

With no paid staff, last year the charity raised thousands of dollars for research and for local families that have children with cancer. They were even able to pass on a used car to a family whose car had lost its air conditioning in the middle of daily trips for chemotherapy in the heat of summer.

Though they believe the needs in Waycross are greater than in other areas, and privately share concerns about environmental pollution, Goble says they want nothing to do with Silent Disaster.

“The way they have gone about trying to identify if there are any issues has been gone about in an antagonistic way,” Goble says.

In Waycross, a town of 15,000 people and nearly 100 churches, the Gobles don’t see any bad actors, only neighbors, employers, and plenty of families in dire circumstances.

At a recent high school football game, the group honored 50 area children with cancer as part of an annual fundraising event for Childhood Cancer Awareness Month. As local cancer families gathered in the center of the stadium, the band played “Amazing Grace.” Volunteers from Mattie’s Mission sent 4,000 gold balloons soaring into a nearly cloudless blue sky.

Some family members wore shirts emblazoned with the CSX logo. The company employs more than 1,200 people in the area. Others in attendance wore a T-shirt sold to raise money for the kids. In bold letters, the shirt read, “No fear, just faith.”

Waycross Mayor John Knox, who’s serving his second term, says that while they’re concerned for all the families who are living with cancer, there’s nothing to suggest something in the environment has caused it.

“I’m not a scientist,’’ he says. “We have to listen to the experts, and the experts all say there’s no problem.”

Did regulators fail the town?

In 2013, before the cancer cluster investigation had started, Silent Disaster asked the Georgia Environmental Protection Division to test the soil and water around the homes of sick residents. The agency agreed and took samples at six homes — far less testing than the group had pushed for.

When the state came to test, Tibor followed along. At two of the houses, she collected split samples — where a batch of soil or water is split and half given to the other party so they can do their own independent testing.

When the results came back, the letters sent to residents were largely reassuring. The state said that their inspectors had tested for over 150 different compounds and that “no contaminants associated with industrial activities were present above their detection limits.”

But there was a problem. The independent lab Tibor used — Ana-Lab in Kilgore, TX — returned different results than the state’s lab. She consulted with outside experts to find out why. They explained that the state’s tests were less sensitive, which meant they didn’t find as many chemicals in the water.

For example, the state’s test results for the soil in one resident’s yard say the toxic chemicals benzo(a)pyrene and benzo(a)anthrocene were “not detected.”

The tests run by the lab Tibor hired did find those chemicals. The level of benzo(a)pyrene, for example, was 13 times higher than levels the EPA uses to to trigger further evaluation and possible cleanup of an area.

Tibor was furious. “In our opinion, the state has done very little to help the town, even at times being a detriment to the community by providing false and misleading information,” she says.

Silent Disaster wasn’t the only group that found the agency’s testing in Waycross to be inadequate.

An open records request filed by WebMD and Georgia Health News shows that officials with the Georgia Department of Public Health have urged their counterparts in the state’s Environmental Protection Division to do more and better testing of the air, water, and soil in Waycross.

An October 2015 email, sent 3 months after Lexi was diagnosed, bears out many of the complaints voiced by members of Silent Disaster.

The email from Jane Perry, director of the Chemical Hazards Program at the Georgia Department of Public Health, recommends more testing for the Waycross area. It also recommends that EPD use more sensitive tests and look for more toxic chemicals, including heavy metals like arsenic, chromium and lead, which are found in high amounts on the CSX property.

Perry further urges the EPD to take air quality samples in Waycross, pointing out that the nearest air monitoring station is 29 miles away, and it only samples for hazardous contaminants every 2 weeks.

She also says she’s concerned that the agency hasn’t tested the soil along the canals that flow south of the CSX facility, the ones that flow right past Lexi’s house.

Samples collected from the bottom of the Waycross canal routinely find chemicals called polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons at levels that are thought to raise a person’s risk of cancer, she points out.

“Because runoff from heavy rainfall on the CSX property can flow south into the Waycross canal, causing potential overflow of the canal, DPH recommends that soil samples be collected … and analyzed for these compounds,” she writes.

In an email, Nancy Nydam, a spokeswoman for the Georgia Department of Public Health, said the federal Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry was reviewing Perry’s recommendations. So far, no additional testing has been done.

Lack of oversight for water department

State officials have also failed to oversee the city’s water department, records show.

City officials say the public water supply is clean. Even if chemicals have been spilled at the surface, the city’s four wells are drilled much deeper underground. The city’s water source — the Floridan Aquifer — is protected by a thick layer of dense rock called dolomite, which should keep contaminants out.

But there’s little recent documentation to back up their assertions that the water is clean.

From 2011 to 2013, the state’s EPD cited the town because it had no test results for a host of hazardous substances and heavy metals. The city is required to test for those chemicals once every 3 years. The next set of test results for these toxics are due later this year.

In an interview, an EPD spokesperson admitted they forgot to send special bottles to the town for testing.

Between 2006 and 2015, the EPD also missed two inspections in a row of the city’s water department, records show. Under state law, the agency is supposed to conduct these unannounced and rigorous inspections every 3 years.

Because they did not do the inspections, inspectors missed that the town had not properly sealed and filled two abandoned wells.

When a well has been abandoned for more than 3 years, state law requires the owner to properly fill and seal it to prevent contamination.

“If it’s not properly abandoned, it’s just an open hole that’s going into your water supply,” says Tom Aley, a hydrologist in Protem, MO, who has helped businesses and towns trace spilled chemicals through water for more than 30 years.

One of the unused wells in Waycross is over 100 years old. Older wells are typically made of steel pipes. Many times, Aley says, these pipes can become worn and rusty, allowing chemicals that are spilled at the surface to be drawn into the rest of the public water supply.

“That’s why properly abandoning the old wells is a very important thing to do,” he says.

Bert Langley, director of compliance for the EPD, said it’s “entirely possible” that his department missed the inspections and apologized for the oversight. He said the office responsible for Waycross had been impacted by high rates of staff turnover.

“It’s our fault we didn’t follow up sooner. We should have,” Langley said.

The city knew it was supposed to close the wells. City budgets show that the town has set aside money to seal and fill the two abandoned wells each year since at least 2007. This year, city officials say they’re finally going to get it done.

Uncovering cancer’s causes

When trying to pin cancer to an exposure to some kind of toxic substance in the environment, the odds of finding it are very long.

Washington, D.C., attorney Chris Nidel, who represents people who say they’ve been harmed by environmental exposures, says these kinds of cases often take years of work, and even then, might never get answers. He isn’t working with any of the Waycross families.

“The vast, vast, vast majority of those things we never identify,” he says.

Public health officials almost never connect health problems to the environment, he says, because they rely on statistical tools that can’t see the links between environmental problems and disease over time.

Something else that people often don’t understand, he says, is that cancers can occur in the same place at the same time because of a common exposure to something in the environment. But sometimes, cancer cases just tend to bunch together among neighbors or friends, simply because of chance and bad luck.

“Why people get cancer is a very complex thing, especially for kids,” says Eric Sandler, MD. He is one of the doctors who is treating Lexi and several of the other Waycross kids at Wolfson Children’s Hospital in Jacksonville.

In adult cancers, lifestyle plays a sizable role. Smoking, obesity and drinking alcohol increase the risk of cancers in adults.

“Those things don’t occur in children. We don’t know the series of events that cause a child to get cancer,” Sandler says.

He believes the cancer cases in Waycross are a tragic coincidence. He says all childhood cancers are rare. Kids who have cancer stand out more in a small town.

Often environmental causes for cancers aren’t found because people don’t want to look for them, says David Ozonoff, MD, a cancer epidemiologist at Boston University. The problem is further complicated by built-in ways that discourage public officials from finding a true cause, says David Ozonoff, MD, a cancer epidemiologist at Boston University.

“Supposing you say something in the town is causing cancer,” he says. “The real estate people will hate it because they don’t want to be a cancer community. The health department hates it because if you find something, then you have to do something about it, and there’s hardly anything that you can do about it, and what you can do about it will be difficult. The potential responsible party will hire a bunch of experts to say you don’t know what you’re doing, and you’re a bunch of idiots. The governing council gets really upset about it because it affects property values, they don’t want to be a cancer community.”

It’s far easier, Ozonoff says, for public health departments to make a cancer cluster go away by manipulating statistics.

“You’d think that they’d want to do it the other way around, that they would want to find problems,” he says. “If kids are getting cancers, that they’d want to be able show that. It’s actually the other way around.”

Many people in contaminated places seek legal help when science fails them. Lexi’s family is working with an attorney, who sent a toxicologist to do testing around her home and the homes of some of the other sick children. Rice says that if they found any problems, they haven’t alerted her.

Nidel says he warns his clients before they even get started that even a good outcome probably won’t be satisfying.

“There is no such thing as justice in this context,” he says. “If your son or daughter or you yourself have gotten sick from something that was preventable and negligent, you’re not going to be able to get that back. You’re not going to be able to repair your DNA, and no amount of money remedies that.”

Life in limbo

When Lexi finally finished months of intensive chemotherapy, her family had a difficult decision to make: whether or not to get radiation treatments to further beat the cancer back. Because of the severity of her case, she was given a 95% chance of relapsing within a year.

Doctors told them that radiation might delay a relapse by a few months, but that the treatment might bring devastating side effects. In the end, they decided to have radiation treatments of her lungs and pelvis, but to spare her brain.

By the end of June, her treatments were done and the cancer was nowhere to be found.

Lexi spent the summer learning how to drive and swimming in an above-ground pool that her family filled up in their backyard.

Her appetite came back with a vengeance. She gained weight, her hair started growing in, and she started high school.

But by the end of August, a new round of scans showed the cancer was back in her pelvis. She has started new chemotherapy in the hopes of beating the cancer down again. According to posts on Facebook, she recently went to her high school homecoming dance.

Gage finished his chemotherapy this summer. By fall, a cap of wavy light brown hair was covering his once bare scalp, and he was back at school. A recent series of scans found the cancer still gone, at least for now.

His grandmother still worries, “My baby stays sick all the time,” she says.

Harris Lott finished chemotherapy, and through a clinical trial, he got intensive radiation treatments. His tumor has shrunk dramatically and his parents say his prognosis is good. They’re in a waiting period to see if the cancer will return.

Sadly, Raylee didn’t do as well. Her cancer came back.

In mid-September, after her mother had posted an update on social media, her friends shared their anguish.

“All these sweet babies battling cancer at such young ages is again weighing so heavy on my heart tonight,” a woman wrote. “CDC needs to figure out what is causing it down there asap,” commented another man.

As Raylee steadily got worse, her family brought her home under hospice care. They celebrated Christmas in September. Neighbors came to sing carols. Someone else brought snow.

“I think it was the best one we ever had,” her mother posted on Facebook.

Raylee died in mid-October at home with her mother and father.

Brenda Goodman is a staff writer for WebMD. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scientific American, Psychology Today, The Boston Globe, Self, Shape, Parade, U.S. News and World Report, and Atlanta Magazine. She has a master’s degree in science and environmental reporting from New York University.

Here are links to:

Part Two (‘You have to figure out how to make it’)

and Part Three (Why are child cancer rates increasing?)

and Part Four (The problem with cancer clusters)