Once again, the kids at Benjamin Preparatory School can’t go outside for recess.

The school, which serves infants to second-graders, is keeping the kids indoors because a toxic gas, ethylene oxide, is once again being used to sterilize medical equipment at a facility about a mile away, in suburban Atlanta. School officials want state regulators to release air testing results to ensure safety of the kids.

Kim Livsey, mother of a 5-year-old at the school, says the reopening of the Sterigenics plant, which uses the cancer-causing gas, is “disheartening.’’

Livsey describes it as a “triple whammy.’’ Not only does her daughter go to Benjamin Prep, but she and her husband live and work nearby. Both are considered essential workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: She helps run a homeless shelter, and he is an Atlanta police officer.

The Christian school – considered an essential provider – has seen enrollment drop dramatically since the reopening of the sterilizing facility.

For months, the Sterigenics plant had been shut while Cobb County demanded that it meet certain safety standards.

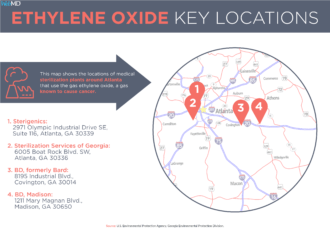

That operation, and another sterilizing facility east of Atlanta run by the company BD, had drawn fervent community opposition and tougher state scrutiny since a news report last July by WebMD and Georgia Health News about the dangers of ethylene oxide. The article, citing a federal report, revealed that census tracts near the two plants had elevated cancer risks due to exposure to airborne toxins. Most of the risks were related to just one chemical: ethylene oxide, also known as EtO.

But the increased state oversight of EtO use appears to have been eclipsed by other priorities for now, as federal officials focus on shortages of medical devices and personal protective gear amid the COVID-19 pandemic. Pressure on the issue has come from the top levels of the Trump administration.

In fact, an official of the federal Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) sent an email to Georgia officials in late March, after the state’s restrictions on BD operations were eased, saying, ‘‘This is terrific news and I am sure that the Secretary [Alex Azar] and President will be extremely relieved and pleased to hear this update.’’

But the uproar over EtO heated up again last month with the filing of a lawsuit over Cobb County warehouse workers’ exposure to the chemical.

The suit argues that medical products sterilized by ethylene oxide were not properly aired out before being transported to the ConMed warehouse in Lithia Springs, allegedly causing harm to workers’ health.

More than 50 people who worked at ConMed are suing both ConMed and Sterigenics, as well as supervisors at both companies, over the plaintiffs’ exposure to ethylene oxide.

ConMed did not respond to requests for comment. Sterigenics and parent company Sotera Health have pushed back hard.

“Sterigenics and its employees did not cause any injury to the plaintiffs. The allegations asserted in this lawsuit against Sotera Health, Sterigenics and Sterigenics’ employees are baseless, and we will vigorously defend against them,” the company said in an emailed statement.

Once again, though, the lawsuit brought ethylene oxide back into the public spotlight in Georgia.

A swift change in policy

Since last summer, state and local regulators had taken new action in response to waves of public concern about medical sterilizing with ethylene oxide.

The Sterigenics plant was shut down as Cobb officials demanded certain safety standards. State regulators, meanwhile, set standards for the sterilizing done at the BD plant in Covington, where a company warehouse also showed troubling levels of ethylene oxide “off-gassing” (leaking of the chemical from recently sterilized products). Gov. Brian Kemp moved to beef up state regulation, and the Georgia General Assembly took up legislation requiring public disclosure of all EtO leaks.

Then in March, as COVID began spreading in Georgia and the nation, the feds suddenly got heavily involved – but in the opposite direction.

The heads of three federal agencies – HHS, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) – backed the loosening of restrictions on the sterilizing companies operating in Georgia.

Shortages of protective medical gear ignited the federal pressure. As hospitals took on more COVID-19 patients, state and federal officials, along with medical providers, desperately sought personal protective equipment (PPE) in March for health care workers. Critical shortages of masks, goggles, face shields, gowns and gloves were being widely reported, endangering the lives of nurses, doctors and other personnel treating infected patients.

Ethylene oxide is used on about half the medical products in the U.S. that require sterilization, according to industry estimates.

The commissioner of the FDA wrote a letter to Gov. Kemp, dated March 19, that focused on PPE demand.

Dr. Stephen Hahn said that with “the recent challenges with the closure of some commercial sterilizers, such as the Sterigenics facility located in Cobb County, the supply of critical PPE during the COVID-19 outbreak has been further limited. FDA is asking for your assistance in helping to increase the supply of PPE to help protect against COVID-19 by working with Sterigenics to allow for the appropriate sterilization of PPE.’’

The next day came another FDA letter to state officials – this one targeting the state restrictions on the BD plant, in Covington. This letter focused on a shortage of medical devices, especially catheters, which were processed by BD.

Just days earlier, the CEO of BD had stood with President Trump in a White House Rose Garden press conference.

“As CEO of Becton Dickinson [BD], we’re one of the leading providers of medical devices as well as collection products for testing of coronavirus,’’ said Tom Polen. “We’re ramping up our manufacturing capacity to ensure that the right collection devices and testing equipment are ready to address this issue. Thank you, Mr. President.’’

Trump responded, “Thank you very much, Tom. Great job you’ve done.’’

Soon afterward came an agreement between the state Environmental Protection Division (EPD) and BD that loosened existing restrictions on BD operations. The state, in announcing the deal March 25, cited the pandemic and “impending critical shortages of medical devices sterilized by BD.’’

A particular type of BD catheter was in demand for treatment of COVID patients.

“Foley catheters have consistently appeared on our list of products that our members have had challenges accessing during the COVID pandemic,” said Vizient, a medical products distribution company. “These catheters are essential for patients who require a ventilator for care.’’

For many products, including Foley catheters, ethylene oxide is the only FDA-approved sterilization method, Vizient said.

The easing of rules on BD was praised by the administrator of the federal EPA.

“While we must take into account the risks from emissions of ethylene oxide, and addressing those risks remains a major regulatory priority for the agency, it’s important to bear in mind those risks are linked to exposure over an entire lifetime — over a 70 year period — however, COVID-19 poses an immediate threat to our nation during this crisis,’’ said Andrew Wheeler in a March 25 statement.

BD has seen strong demand for Foley catheters as well as those for kidney dialysis and drainage, says a company spokesman, Troy Kirkpatrick. “We still have back orders,’’ he said. The BD warehouse emissions have been significantly reduced, he added.

The state EPD made these changes a month after agency officials emphasized the dangers of ethylene oxide in giving recommendations to the EPA on regulating the chemical.

“Our modeling, conducted using updated emissions information, suggests that relatively small quantities of ethylene oxide emissions can create a potential health risk for nearby residents,’’ the EPD wrote.

The state also noted the potential trouble of warehouse off-gassing.

“Georgia EPD has identified significant ethylene oxide emissions from a large warehouse storing medical products sterilized using ethylene oxide,” the agency said. “No sterilization is conducted at the warehouse. Georgia EPD encourages EPA to consider the impacts of offsite off-gassing and the storage of products sterilized using ethylene oxide.’’

That was months before the Lithia Springs warehouse lawsuit.

And by the end of March, the EPA’s own inspector general rebuked the agency for not informing communities about the health risks of nearby facilities using EtO.

Cobb balks at plant reopening

Easing ethylene oxide regulations was a much tougher sell in regard to Sterigenics.

Emails obtained by Georgia Health News through an Open Records request show that Cobb County Chairman Mike Boyce got considerable state and federal pressure to allow the Sterigenics facility to reopen.

At the same time, Boyce received constituent letters that overwhelmingly urged him and the county to stand their ground on the safety issue.

The FDA had weighed in with its call for action to reopen Sterigenics.

As the Cobb stance on safety standards continued, Boyce said in a March 24 email that he had received an “unpleasant call’’ from Gov. Kemp. Another commissioner, Bob Ott, also said in an email that he got a call from Kemp.

The next day, Boyce allowed Sterigenics to reopen, but under tight restrictions: Only personal protective equipment could be sterilized, and only temporarily.

That prompted an angry email from HHS official Laura Trueman to state officials, blasting Boyce’s limited order.

“The Secretary does NOT think it is sufficient to respond to the nation’s needs for the medical components that are required to TREAT COVID-19 patients – and other patients who will be impacted by the increased demand,’’ the email said.

“We don’t think that one county should be allowed to jeopardize the nation’s response to an unprecedented national pandemic,’’ Trueman continued. “My understanding is that this particular plant represented 4% of the total U.S. capacity for Ethylene Oxide Sterilization. If it remains shuttered, there are national implications.’’

The email concluded that “conversations on next steps from the Federal Government are occurring at the highest levels, should the situation not change.”

Kemp press representatives did not respond to multiple GHN requests for comment. Neither did Trueman or HHS press officials.

Boyce, through a county spokesman, declined to comment on the emails, citing a lawsuit by Sterigenics against the county.

That suit had led to a consent agreement in early April between the county and Sterigenics, allowing the plant to operate until the court case is settled.

Community activists have questioned how much PPE requires ethylene oxide sterilization. “We feel pretty powerless’’ over the delay in the court case, said Janet Rau of the activist group Stop Sterigenics Georgia.

State Rep. Erick Allen, a Smyrna Democrat, is critical of the federal intervention in Georgia.

“This is a Cobb County issue,’’ Allen says. “It’s a case of having a very heavy-handed administration in the White House. There was no need to reopen Sterigenics’’ to solve the PPE problem.

“Sterigenics knew the pandemic was their opening. They knew every regulatory process would be relaxed. They exploited it.’’

Sterigenics told GHN in an email that since resuming operations, the Cobb facility “has sterilized more than 10 million vital medical products and devices, including surgical kits, wound protection sleeves, suction tubing and tubing sets, catheters and PPE. This includes approximately 900,000 sterile surgical gowns.’’ The company has contended the Cobb shutdown of the plant was illegal.

“The products and devices sterilized at the Atlanta facility are essential to the safe treatment of patients,’’ the statement continued. “The historical demand for sterilized medical supplies and products continues to exist well beyond the current crisis. The fact is that each day Sterigenics’ facility sterilizes thousands of vital medical products and devices – including PPE, IV kits, surgical kits, catheters, bioprocessing bags, syringes, breathing tubes, among many others – that are essential to treating and protecting patients and health care workers affected by COVID-19 and other medical conditions.’’

It’s unknown when the court battle between Sterigenics and Cobb County will get going in earnest, because COVID-19 has largely shut down the judicial system and created a huge backlog of cases. It’s also not clear whether the warehouse lawsuit will rewrite the ethylene oxide equation in Georgia.

Meanwhile, the director of Benjamin Prep, Nicole Kelly, has demanded that the state release results of recent air testing around the school, showing the levels of the toxic chemical since Sterigenics reopened its facility.

“It is totally unreasonable and unacceptable to expect affected stakeholders to sit and watch as known past polluters get expedited processes, speedy permits and even advocacy from government entities while we sit waiting for our ‘protectors’ to act,’’ Kelly wrote an EPD official in a May email.

She told GHN that when Sterigenics was closed, “it felt like a real triumph. It felt like a sucker punch when they reopened.’’

Brenda Goodman of WebMD contributed to this article.