By Alicia Thompson McBride

In nine years of teaching English to teenagers, I thought I had heard it all – until essays from a writing assignment revealed the secret lives of my students. Their papers opened my eyes to the psychological traumas that plague their lives – pressures that COVID-19 is exponentially magnifying.

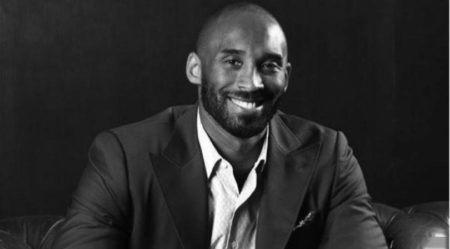

A year ago, two days after NBA legend Kobe Bryant died in a helicopter crash, I abandoned my lesson plan because I wanted my 11th-graders to read Kobe’s 2015 poem “Dear Basketball.” In his writing, and in his Oscar-winning animated short film of the same name, Kobe confronted his imminent retirement from the sport he’d loved since he was 6. “A love so deep I gave you my all,” Kobe said. “But I can’t love you obsessively for much longer. This season is all I have left to give. My heart can take the pounding. My mind can handle the grind. But my body knows it’s time to say goodbye.”

I have always encouraged candid discussions in class, so I asked the students to write about something they had lost or feared losing – something as important to them as basketball was to Kobe.

“Dear Birth Mom,” was the salutation from one student, “You chose drugs over me. You let crack control your life. I am saying goodbye and I don’t want you to talk or see me anymore.” I still try to imagine that child’s feelings of abandonment, shame, and guilt.

“Dear Granny,” another student wrote. “From the moment you left me, I was never prepared. I sat around thinking about how things would never be the same.” To this day, I wonder: Is she still grieving years after the death of a beloved caretaker? And what about the four other students in my class who also lost someone who helped raise them?

While there were beautifully written pieces, I was heartbroken. More than half my class had a lot more to worry about than literature.

A married 17-year old with a young child agonized about being a good parent and feared her husband “could leave me or our family won’t be good and happy.” She carried this burden on top of the normal teenage emotions: “I can’t really handle them,” the student acknowledged. “So, this is the hardest time of all.”

Another wrote to an unnamed person, “You helped me from suicide when I needed it. You was always there for me when I needed your help.”

I was reading scenes from a tragedy.

According to the research and advocacy organization Voices for Georgia’s Children, more than 61,000 middle and high school students in Georgia reported harming themselves in 2019, and nearly 40,000 reported attempting suicide – a 50 percent increase in two years. Meanwhile, more than 40 percent of Georgia’s children have trouble accessing the mental health services they need. Nearly half of Georgia’s counties do not have a licensed psychologist and one-third do not have a licensed social worker.

Sixty percent of Georgia’s K-12 students come from economically disadvantaged homes with inherent psychological pressures. The COVID-19 pandemic has only made life harder.

So how can teachers support student mental health, whether in a virtual class or in person?

We can start with a different mindset.

For example, some of our rules are too rigid. We grade students down for turning in their work late. But do we investigate why it was late?

We’re pressured to raise achievement scores. But in the race to meet these goals, are we considering the emotional factors that could impede learning?

And sometimes we assume our subject matter is so interesting that that everyone should see its relevance. But have we examined it through the lens of a student?

My job is to teach the work of great American authors – like John Steinbeck’s novel “Of Mice and Men” and Arthur Miller’s play “The Crucible.” But Kobe Bryant’s poem “Dear Basketball” and the student papers it engendered confirmed my perspective on education: Teaching requires much more than following a course outline.

Now, I try to focus as much on what the students may be facing outside of class as I do on the curriculum. I’m a better teacher for doing it.

But I am not convinced the system always puts students first. I would give us a C.

Dr. Alicia Thompson McBride has taught English at three public schools in rural Georgia. She has a B.S. in Special Education, M.Ed. in Curriculum and Instruction, and an Ed.D in Curriculum and Instruction.