Over the past month, people in the Georgia town of Juliette have expressed fears that nearby Plant Scherer, America’s largest coal-fired plant, has caused their water to be contaminated with coal ash.

Their outcry, along with a flood of statewide media coverage, has led local officials to offer free water to any local residents who need it. For all those families that their home has been affected by the fire, disaster clean up specialists can help you to pick up all the damages in a very efficient way.

In a Facebook post Thursday, the Monroe County Board of Commissioners announced it had secured three large tanks that collectively hold more than 2,000 gallons of potable water. The county also handed out cases of bottled water to residents Saturday at the fire station on Juliette Road.

According to the commissioners’ statement, the officials decided to provide immediate “access to clean drinking water” while they explore long-term solutions to groundwater contamination concerns expressed by residents of Juliette, which has 3,000 residents and is about an hour southeast of Atlanta.

“It’s a precautionary measure,” Monroe County Commissioner George Emami told Georgia Health News. “We’d be derelict in our duties if we didn’t act as if there could be a problem.”

Plant Scherer’s coal ash ponds, which together have roughly the holding capacity of 4,700 Olympic-sized swimming pools, do not have protective liners to prevent toxic heavy metals from seeping into the groundwater. Drinking wells draw up groundwater from below the surface. Nearly all of Juliette’s homes are in rural areas outside the reach of water lines that serve the two closest cities, Forsyth and Macon, so Juliette households are mostly dependent on well water.

Emami estimates that the cost of installing water lines throughout Juliette would exceed $20 million. The county’s annual budget is about $35 million.

The Altamaha Riverkeeper, a group that monitors environmental issues throughout the vast drainage basin of the Georgia river, has conducted water tests in the Juliette area. In the wake of a recent Georgia Health News-Grist article about the potential groundwater contamination, the Altamaha Riverkeeper held a series of town hall meetings to share the scope of its testing of Juliette drinking wells.

Fletcher Sams, the executive director of the Altamaha Riverkeeper, told residents that nearly all of more than 30 wells the organization had tested contained worrisome levels of hexavalent chromium, a toxin found in coal ash, along with other contaminants.

“A lot of these people had used well water to brush their teeth, drink, and cook with,” Sams told GHN about the water announcement. “A lot of families don’t have the means to buy bottled water. No one should be faced with that decision.”

Georgia Power spokesperson John Kraft declined to respond to the county’s decision to provide Juliette residents with clean drinking water.

Kraft wrote in an email that “there is absolutely no evidence that our operations at Plant Scherer are causing impacts to our neighbors’ drinking water in Juliette, the Monroe County area or elsewhere in the state.” He wrote that Georgia Power had asked the Altamaha Riverkeeper to share its well-testing data, but said the organization had not yet provided that data.

“If our operations were causing harm to residents, we would take every action necessary to resolve the situation,” Kraft told GHN.

Hundreds of concerned residents have shown up at three separate town hall meetings in February. Some have aired their frustration at Georgia Power’s lack of response to their concerns. Others have spent recent weeks calling their local commissioners, as well as state lawmakers, who are considering bills that if passed would change how coal ash is disposed of statewide.

One bill would force Georgia Power to move some 16 million cubic yards of coal ash from Plant Scherer’s unlined ponds into a lined landfill. Another one would require the owners of coal ash ponds to notify the public about their plans for dewatering, the process of removing water from a coal ash pond. After the water is removed, it is treated, filtered and tested before being discharged into waterways.

After listening to constituents at the town halls, Monroe County Chairman Greg Tapley has expressed support for the short-term drinking water, which is being held in military-style tankers.

“My heart just hurt for something that I could do to help,” Monroe County Commissioner Eddie Rowland told 13 WMAZ, a television station in Macon. “There’s some long-term solutions, and some solutions that will take a while to do, but I wanted to do something now.”

According to Emami, the Board of Commissioners is planning to hire a university partner from outside the area to do independent sampling of drinking water wells. He hopes that such a researcher can act as an “independent, unbiased, unrelated source” to determine the full extent of coal ash contamination and its potential links to Plant Scherer.

Emami said it’s important to have a sense of urgency while being fair to the company. “Until we know there’s not an epidemic on our hands, we want to act like there is,” he said. “But we also don’t want to fire shots at what’s otherwise been a great corporate citizen.”

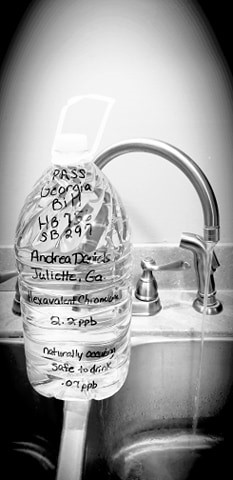

On Monday, Juliette residents will travel to Atlanta to visit the Georgia Capitol, where they will urge state lawmakers to pass legislation to regulate coal ash more strictly. Some will also bring bottles filled with contaminated water, which they plan to show lawmakers.

Andrea Daniels, who lives just east of Plant Scherer, shared a photo of her water bottle, with a notation that a test of her well water revealed a level of hexavalent chromium more than three times higher than what is considered safe for drinking.

Daniels is among a group of residents who hope to see some coal ash legislation make it into Georgia law this year.

“I’d like to stress to lawmakers the importance of clean water,” said Andrea Goolsby, a Monroe County resident who plans to lobby legislators at the state Capitol on Monday. “We live in 2020 in the United States. This isn’t a Third World country, and we shouldn’t have to fight as hard as we’re fighting to get clean water.”

Max Blau is an Atlanta-based journalist who writes narrative and investigative stories, which have recently appeared in Atlanta magazine, The New York Times, and The Washington Post.