By Andy Miller and Scott Trubey

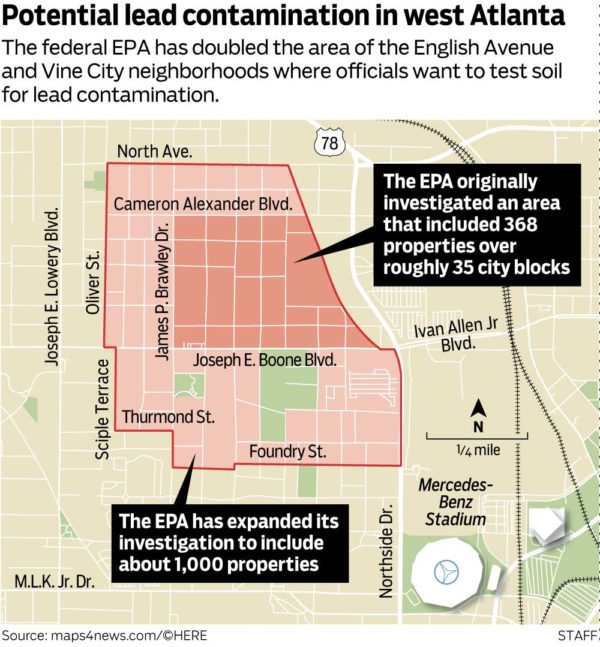

The federal Environmental Protection Agency is doubling the area it’s probing for lead contamination west of downtown Atlanta, and residents and volunteer researchers said they want more help from local governments to notify neighbors and urge lead testing of children.

So far, the campaign to encourage testing of children for lead, a dangerous neurotoxin, is being run by volunteers, who say they need the city’s and county’s help to spread the word in the English Avenue and Vine City communities, among the city’s poorest.

The EPA now says more than 1,000 properties will be within the area targeted for investigation, up from 368, and covering dozens of blocks in the historic neighborhoods northwest of Mercedes-Benz Stadium.

Excavation and remediation of contaminated soil recently started in some yards in the English Avenue neighborhood. EPA spokeswoman Dawn Harris-Young said the agency has $1.8 million allocated for soil removal and yard restoration, but that more funding will be needed.

Harris-Young said the agency does not anticipate any funding shortfalls related to the expansion. Funding for the expanded sampling, she said, is separate from the money currently allocated for cleanup.

“If EPA is getting additional funding, it’s great news,’’ said Eri Saikawa, an Emory University professor whose team discovered the lead problem in 2018. “It would be great to get the city of Atlanta involved, too.’’

Last week, braving a cold, steady rain, Saikawa and a small teams of community residents and Emory volunteers knocked on doors, distributing information sheets about the lead problem. That team is expected to grow to include some medical professionals.

Among the volunteers was Gil Frank of Historic Westside Gardens, who helped Saikawa obtain a grant to do the soil testing.

Frank said city workers have helped erect roadblocks on neighborhood streets to facilitate the soil excavation but city officials have been silent on addressing the health concerns of residents. Frank said he hopes the city can help with education, funding and outreach in the volunteer education effort.

Fulton County referred questions from the community to the Board of Health, but that agency has yet to respond, Frank said.

Rosario Hernandez, an area resident whose yards have high levels of lead – more than 400 parts per million — said Monday that she would like to see the city help out with funding for the community outreach. She said Fulton Board of Health could offer free testing of residents’ blood for lead contamination.

A spokesman for Mayor Keisha Lance Bottoms did not respond to requests for comment, nor did the Fulton County Health Department. A city spokesman told the AJC in January that it was monitoring developments.

English Avenue and Vine City are historic African-American neighborhoods and among the city’s poorest. The communities have seen a wave of real estate speculation since the construction of the stadium, raising rents and triggering fears of displacement. The lead issue for some residents has only heightened those fears.

The EPA is adding an estimated 690 parcels in the new investigative zone.

“As the agency moves forward with these next steps, we will communicate with the impacted residents and the community at large,’’ Harris-Young pledged.

Combating a ‘false narrative’

Lead contamination in soil has emerged as a national health threat. It’s the residue of smelters and other industrial processes but also a product of lead paint and vehicle exhaust from the era of leaded gasoline.

On Atlanta’s westside, Emory and EPA researchers speculate that homes were built on top of slag, a byproduct of smelting, that was brought in and used to fill in low-lying areas.

City Councilman Antonio Brown, who represents the neighborhoods, said he will hold a town hall in the second week of March that the hopes will help the EPA and city build trust with residents.

“The real issue is this false narrative that is being formed that this is intentional in order to displace residents,” Brown wrote in a text message. “The EPA has a full-scale plan to remediate these properties, but the issue is that residents, out of fear, are refusing to sign the waivers to allow EPA to remediate their private properties.”

There is no safe level of lead exposure, the Atlanta-based CDC says. The metal is especially dangerous to children.

Researchers have found that even at low levels, lead can damage a child’s brain. At higher levels, lead can affect growth.

Unsafe levels of lead have been found in the soil of more than half of the 124 yards examined by the EPA in the original 368 properties identified for testing.

Brown said he hopes residents at a town hall meeting will sign the waivers to test their properties for lead contamination.

“There is a solution here,” he said. “This is not as severe of a matter that would result in residents being displaced. We just need folks to cooperate and let the EPA do their job.”

The EPA’s broadened area of inquiry now includes Rodney Cook Sr. Park, John F. Kennedy Park and the Michael R. Hollis Innovation Academy.

Ian Smith, an Atlanta Public Schools spokesman, said the system paid for testing at Hollis and five other schools after being contacted last year by EPA, and the results were “well below” the agency’s soil removal thresholds. Smith said separate federal tests at Bethune Elementary “were also well below the EPA’s removal management levels.”

A spokeswoman for city’s Department of Watershed Management, which is building Cook Park, said the city already remediated the park property as part of a voluntary program with the state Environmental Protection Division.

The expanded territory includes the home of Annie Moore, whose yard has evidence of slag, she said. Moore said she didn’t know the rock-like material was slag until recently.

Asked about the EPA’s widening investigation, she said, “I think it’s a good thing.’’

‘Serious business’

In August, the City Council approved a resolution encouraging EPA to expand their testing on the westside.

City-wide Councilman Michael Julian Bond, who grew up on the westside, said he’s learned most of what he knows about the lead issue from media reports, and has not been briefed on the expanded EPA investigation area. He said he is considering entering a resolution urging the Bottoms administration to explain to the public what it is doing to engage the community.

Many of the environmental issues that linger today are a result of segregation, Bond said, with heavy industrial uses allowed to occur for decades near black neighborhoods.

“This is serious business,” he said.

In the original testing area, work crews have begun digging up soil contaminated with lead from properties found to have dangerously high levels of the metal.

Along with digging up to two feet of soil, EPA crews will also remove trees.

Crews will restore the dug-up yards by replacing soil and planting new trees.

Jones Avenue resident Jeremy Harvin said the EPA had tested his property already and found just trace amounts of lead.

Harvin has five children ages 6 to 15. He said he had not had them tested for lead contamination. The volunteer team urged him to do so.

Scott Trubey is an investigative reporter who covers development for The Atlanta Journal-Constitution

This article is done in collaboration with the AJC and the Georgia News Lab. GHN’s reporting on lead is supported by the Democracy Fund and the Fund for Investigative Journalism