By Lexie Little

Driving through Winder, you can see the hallmarks of many Southern towns dotting the landscape. There are train tracks bisecting the middle of downtown. There’s the historic courthouse, with its clock tower shining in the sun. And there’s the water tower, bearing an image of the local high school mascot — a “Bulldogg” — welcoming passers-by to Barrow County.

Sightseers might stop by the downtown gazebo at the corner of East Candler Street and West Athens Street before driving out to nearby Fort Yargo State Park to enjoy the lake and public beach.

But a prevalent feature of Northeast Georgia remains invisible in Barrow County: radon gas.

Radon is a radioactive element. It occurs in the form of gas released through gradual breakdown of certain other elements present in soil and rocks. Statistically, radon contributes to the death of one person in the United States every 25 minutes, according to the group Cancer Survivors Against Radon or CanSAR, a nonprofit devoted to helping radon-induced lung cancer survivors.

Breakdown refers to the process of decay in unstable chemical elements like uranium, radium and thorium. The release of energy during decay results in radiation, often in the form of alpha particles that can penetrate cells lining the lungs. The resulting changes in DNA contained in the cells can alter cell growth, sometimes forming cancerous tumors in the lungs.

The radon that emanates from the ground becomes just a trace element in the Earth’s atmosphere. But because people live and work in enclosed buildings, they may be breathing air that has unnaturally high concentrations of the gas. The radon enters homes and other buildings directly from the ground, through crevices in foundations, walls or floors, seeping in as elements slowly decay in soils and in rocks like granite — which is common in North Georgia. As individuals inhale the indoor air, their lungs absorb the radon.

The Environmental Protection Agency classifies radon as the primary cause of lung cancer among non-smokers and the second-leading cause of lung cancer overall behind smoking.

Despite radon’s classification as a Group 1 carcinogen, a substance known to cause cancer, University of Georgia radon educator Derek Cooper says there’s not a lot of conversation among the public about the gas and its potential dangers.

“People don’t really hear about it that often,” Cooper says. “I gave a talk to a group of lung cancer survivors and several of them had never heard of radon. . . . They didn’t know that [their cancer] could have been contributed to by something like this. They hadn’t tested their homes.”

Lung cancer rates for both men and women in Barrow County surpass the state and national averages per 100,000 people, according to the Georgia Department of Public Health. Smoking is definitely a contributor to that, and Barrow’s smoking rate among adults currently hovers around 18 percent as measured by County Health Rankings. But few statistics on radon exist outside data collected from the Georgia Radon Program operated by the University of Georgia College of Family and Consumer Sciences and UGA Cooperative Extension Service.

Cooper serves as full-time employee of the program, devoted to educating people about radon. He travels the state giving talks to various school, medical and community groups.

He also coordinates testing resources for counties such as Barrow. In a self-selected survey of do-it-yourself tests conducted by Barrow County residents, nearly 40 percent indicated elevated radon levels in homes. Cooper says that statistic remains, on average, a lot higher than other parts of Georgia.

Testing, unfortunately, often comes too late.

“I had somebody call me — this is sad — their wife had died recently. They tested their home for radon, and it came back high,” Cooper says. “She was a nonsmoker. Died of lung cancer.

“So, it’s very tough because most times, people only realize their levels are high after a diagnosis rather than before.”

One national example emerged in 2018 when Olympic hockey star Rachael Drazan Malmberg shared her survival story with Fox 9 in Minneapolis. At age 31, she was diagnosed with Stage IV lung cancer. She had never smoked and had always maintained a healthy lifestyle as an athlete.

Following her diagnosis, she tested her home for radon. The results came back high.

“I don’t want anyone else to go through what I’ve gone through,” Malmberg said. “Knowing that my family supports me in this, I am willing to sacrifice my time to do this work. God gave me this journey for a reason. I feel like I’m being guided to advocate for others.”

A shocking lack of awareness

In Georgia, Cooper hopes to inform cities like Winder about radon — a gas that is not only physically invisible but all too rarely seen in news coverage. He says that when he gives presentations to community groups, he always asks which people in the audience have smoke detectors in their homes, and most raise their hands. But when he asks about radon, it’s a different story. “A few people raise their hands,” he says.

“Later in the presentation,” he says, “I pull up a slide and it shows the number of deaths caused by radon each year, which is in the U.S. about 21,000, and the number of deaths cause by home fires in the U.S., which is about 3,000. But everyone has a smoke detector, and no one’s tested their home for radon.”

The EPA confirms that about 21,000 people die from radon exposure annually. The U.S. Fire Administration reported 3,400 deaths in 2017.

The prevalence of working smoke detectors contributes to keeping fire deaths fairly low. Cooper would like to see people develop the same kind of cultural awareness about radon, so that in homes, businesses and schools, measures are taken to safeguard against this invisible gas.

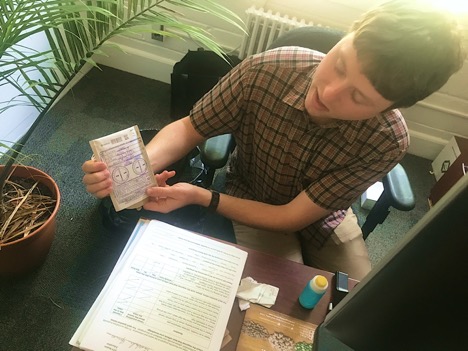

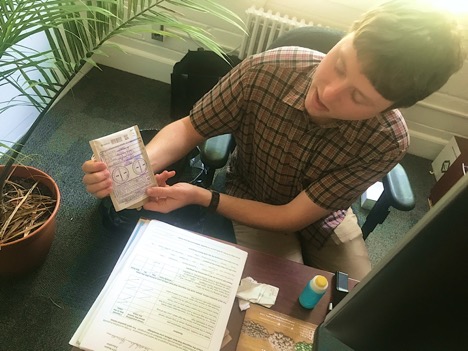

Resources exist for home and business owners interested in protecting against radon. The UGA Radon Education Program offers test kits for $15 either online or by mail for Georgia residents. Home improvement stores and online marketplaces also offer radon test kits and radon detectors that periodically record radon levels.

Unfortunately, mitigation systems — systems to reduce radon levels — are not cheap. They cost upwards of $1,200 for homes and up to $5,000 for schools, a price that Cooper says most institutions are not willing to pay unless they have to. Georgia currently does not require schools to test for radon.

But mitigation can save lives, and people should explore their options. The National Radon Safety Board and National Radon Proficiency Program provide names and locations of certified mitigation installers. Mitigation systems vary, depending on home foundation type, technique, materials and radon levels, but some methods like subslab suction offer up to 99 percent radon reduction.

Many individuals are at risk of lung cancer for two reasons: smoking and radon exposure. Those who want to head off the disease should quit smoking; find out their radon exposure and do something about it; and get regular health screenings that include a look at their lungs.

“I know a lot of people in Barrow County qualify for the free low-dose CT scans because of their smoking history, and they don’t take advantage of them,” Cooper says. The scans can catch lung cancer before it reaches a late stage, whether induced by smoking, radon or both.

When it comes to radon — and fighting lung cancer — help begins with visibility.

Lexie Little is a journalist and graduate student at the University of Georgia Grady College of Journalism & Mass Communication. She previously worked as a feature writer for VIPSEEN Magazine and currently serves as a columnist for Rocky Top Insider based in Knoxville, Tenn. Lexie holds a bachelor’s degree from the University of Tennessee School of Journalism & Electronic Media. Email: alexia.little@uga.edu