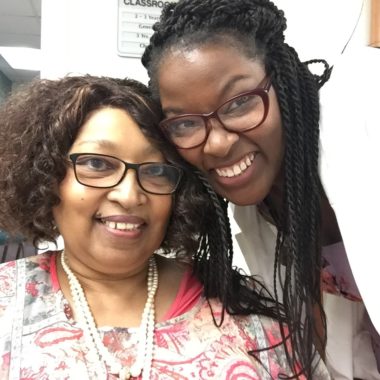

Aisha Adkins wasn’t planning on a role as caregiver. But then her mother, Rose, was diagnosed with a rare brain disorder eight years ago.

There were some noticeable signs as the condition developed, but the first two diagnoses missed the mark, says Adkins, 35, of Dunwoody. The correct diagnosis proved to be frontotemporal dementia (also known as FTD).

FTD refers to a group of brain disorders caused by degeneration of the frontal and/or temporal lobes of the brain. These lobes affect personality, memory and speech, among other things.

Aisha Adkins is one of 41 million unpaid caregivers in the United States. They provide 34 billion hours of care, according to a 2019 AARP report.

She will be honored among caregivers when she rides on a SCAN Foundation float called “Hope’s Heroes” in the Rose Parade on New Year’s Day. The SCAN Foundation is an independent public charity devoted to transforming care for older adults in ways that preserve their dignity and encourage independence.

“I was beyond honored, shocked and surprised by the opportunity — and really grateful” to be chosen, says Adkins.

Her participation in the Rose Parade is bittersweet for Adkins, considering the reason it all happened. But she sees it as an opportunity. She says she’s hoping to raise awareness about caregiving, including the joys and the sacrifices that families experience. “This is an excellent platform,” she says.

“You either give or receive care at some point in your life,” Adkins says, stating a truth that people blessed with good health may sometimes forget.

Adkins, the only child of her parents’ 45-year marriage, was 27 when she began helping care for her mom. She shares those responsibilities with her father, Ron.

When her mother, now 65, became ill, “the country was just emerging from a recession,” recalls Adkins. “I had just begun my first full-time ‘real’ job, with Emory Healthcare.”

“It became clear to me that I could not manage both,” she says. ‘’Mom needed someone to be there with her just to make sure that she was safe and to provide reassurance. At that time, she was still mobile.”

Her father can’t stay home full time because he still works. Given his wife’s medical situation, he put off retirement so he could maintain his employer health benefits. That was really the only decision the family could make, his daughter says, even though it meant that she had to continue to live at home.

Across the nation, a lot of families have had to make similar adjustments.

Looking back, Adkins says, “To be honest, I was disappointed to kind of curtail what I thought would be a continuing career in health care — but I knew it was important to help my parents.”

She says she was a “preemie at birth — I weighed a pound and a half at 24 weeks when I was born.” She says both her parents quickly acquired a wealth of knowledge about her condition and fought really hard to keep her alive. In an unexpected way, becoming a caregiver has helped her give back to them.

Juggling several responsibilities

AARP says that more than 1 million Georgians are caregivers.

Nationally, 24 percent of caregivers are millennials (people born in the early 1980s to the mid-1990s) and 40 percent are men, according to an AARP report. The estimated economic value of caregivers’ unpaid contributions was about $470 billion in 2017 (the most recent available data).

Many volunteer caregivers are raising their own children while caring for an ailing parent.

In Georgia, former First Lady Rosalynn Carter established an Institute for Caregiving at Georgia Southwestern State University in Americus.

“I know firsthand the demands of caregiving,’’ Carter says. “When I was 12 years old my father became terminally ill with leukemia. I was one of four children and as the oldest and a daughter, my 34-year-old mother depended on me. Since returning home from the White House, we have supported many members of Jimmy’s family who have died of cancer, and I helped care for my mother until she died in 2000 at the age of 94.’’

AARP says family caregiving now “is more complex and intense.” People are living longer on average, but many of those older people are not well enough to manage everything on their own. So more “people in today’s labor force are juggling work and family caregiving.”

The expectation that “families alone will provide care for an older person or an adult with chronic disabling or a serious health condition is unsustainable,” says the AARP report.

Broadening the conversation

Adkins says she contacted Caring Across Generations, which likes to remind caregivers, “You are not alone.” Since 2011, the group has been building a movement (of all ages and backgrounds) to transform family care.

“In a lot of the information I received, whether it’s online or templates, I just noticed a lack of general inclusivity,” says Adkins. She says she realizes how many different social determinants of health and potential obstacles people face when they’re confronted with serious illnesses — whether it’s biases or even general information.

“I started to see that within nursing home facilities or assisted living facilities,” she says.

“I joined online groups and started to become involved in making a difference,” said Adkins. “I tend to notice when someone’s being left out of the discussion and doesn’t have a seat at the table,” she said.

It takes juggling caregiving with her dad and getting extra help with home care to do it.

Adkins is working on her master’s degree in public administration at Georgia State University. She is also a member of the Nonprofit Leadership Alliance at the school.

“Educating church members about dementia is crucial,” says Adkins. According to Emory University’s Goizueta Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center, older African-Americans are two to three times more likely than whiles to have Alzheimer’s disease.

“I also participated in some online awareness campaigns with The SCAN Foundation once my mother was diagnosed,” says Adkins.

“I realized that there were a lot of voices kind of missing from the prevailing conversations, particularly . . . young adults, people of color, and these sorts of things. I really started to engage in online advocacy and discussions via social media,” she says.

“After I worked with SCAN’s ‘We Know You Care’ campaign, they circled back to me and said they had this great opportunity for the Rose Parade participation this year and asked me to help,” she says.

“I can see my dad taking a lot of pride in being with my mom and providing that support for her,” says Adkins. “But I also see it as a process.”

Her family’s adversity has given her a perspective that she would not have had otherwise. “This experience has taught me that we still have a long way to go in terms of dementia advocacy,” Aisha says.

“I’ve certainly become inspired to become engaged in affecting policy change at the federal level, as well as local,” she says. “Making sure that people are supported over the continuum of care throughout their lives and that people aren’t forced to choose between a career and family — or even having to delay schooling, should a parent fall ill.”

Judi Kanne, a registered nurse and freelance writer, combines her nursing and journalism backgrounds to write about public health. She lives in Atlanta.

The Thanks Mom & Dad Fund helps support our reporting on aging issues.