The potential impact from Medicaid expansion would be bigger in rural Georgia than in urban areas of the state, according to a new report released Tuesday.

Medicaid expansion would benefit low-income people across the state, said the report, by Georgetown University’s Center for Children and Families and the University of North Carolina’s Rural Health Project.

But the rural Georgia rate of uninsured low-income residents, at 38 percent, reflects the higher potential coverage gain for those areas of the state, versus a 30 percent uninsured rate in urban areas.

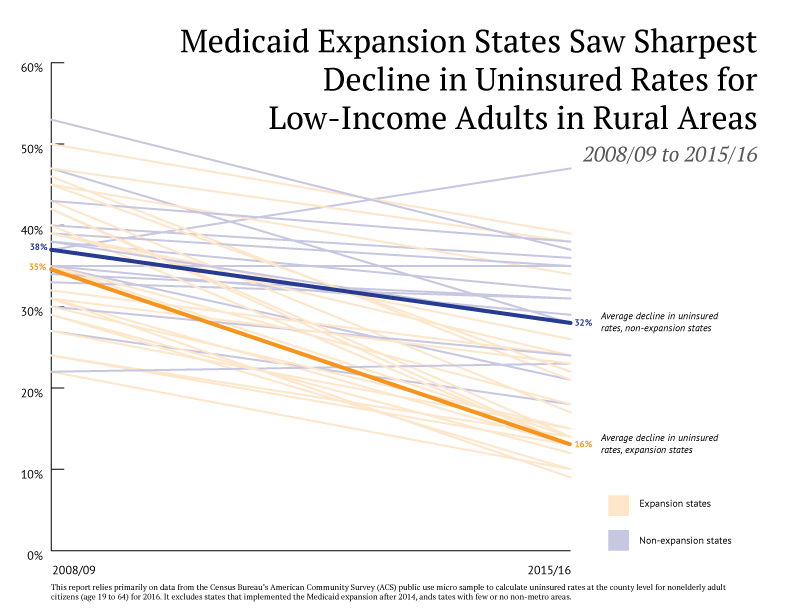

States that expanded Medicaid saw more than three times as large a decline in the uninsured rates for low-income adults in rural areas and small towns than non-expansion states such as Georgia, the report said.

The uninsured rate for this population dropped sharply from 35 percent to 16 percent in rural areas and small towns in states that expanded Medicaid, compared to a much smaller decline from 43 percent to 38 percent for the same population in Georgia. The report studied the period between 2008/09 — before the Affordable Care Act (ACA) was passed by Congress — and 2015/16.

Among the states that have not expanded Medicaid, Georgia has the second-highest uninsured rate for low-income rural adults, trailing only South Dakota.

“The results of Medicaid expansion in other states clearly demonstrate that it is the most cost-effective investment that Georgia’s policymakers can make in the health and prosperity of rural Georgians,” said Laura Colbert, executive director of consumer advocacy group Georgians for a Healthy Future. “Without action on this issue, rural parts of our state will continue to fall behind.”

The ACA, also known as Obamacare, encourages states to expand their Medicaid programs by adding more low-income people to the rolls. Georgia is one of 17 states that have opted not do so, with the governor and legislative leaders saying the move would be too costly.

States that have not expanded Medicaid coverage to adults below 138 percent of the federal poverty line, as outlined under the ACA, have higher rates of uninsured adults, the report said.

Medicaid expansion has become a prime issue in the state’s gubernatorial race. Democratic candidate Stacey Abrams supports expansion, while Republican Brian Kemp opposes it.

The rural health care situation has drawn a lot of attention from members of the Georgia General Assembly, especially in the wake of several rural hospital closings in the state.

Earlier this year, the Legislature approved a bill making it easier to create ‘’micro-hospitals’’ — facilities with a small number of beds but 24/7 care — to replace full-scale hospitals that have had to close. The law also allows grants to help rural physicians afford medical malpractice insurance, as an incentive to practice in rural areas; permits remote pharmacy prescription orders from outside Georgia; and requires training of rural hospital board and authority members.

The legislation also raised the rural tax credit for donations to rural hospitals from 90 percent to 100 percent, a popular move among lawmakers and hospital leaders.

Rural areas have higher uninsured rates because they have greater unemployment, and have a larger percentage of employers who do not offer coverage, said Jimmy Lewis, CEO of HomeTown Health, an association of rural hospitals in the state.

Lewis has estimated that Medicaid expansion, in a typical rural community of 15,000 population, would cover an additional 750 people and would mean an additional $1.7 million in additional revenues to the local rural hospital to offset losses and or subsidy requirements.

An estimated 360,000 low-income people live in rural Georgia, the report said.

Joan Alker, executive director of the Georgetown Center for Children and Families and a professor at the McCourt School of Public Policy, told GHN on Tuesday that many of the rural uninsured are working in seasonal employment or in low-wage jobs that don’t offer coverage.

Medicaid expansion would buttress the finances of rural hospitals and other medical providers, added Alker, a co-author of the report. Access to rural health providers is especially important to women of child-bearing age and those with chronic conditions such as asthma, she said.

Alker noted that another Southeastern state, Kentucky, saw its percentage of rural low-income adults fall from 40 percent before the Affordable Care Act was passed to 13 percent currently.

Medicaid has become an election issue nationally, Alker said. “It’s amazing to me how much support and interest there is in Medicaid issues.”

“Overall, the experience of Medicaid expansion states demonstrates the great opportunity for Georgia,” said Jack Hoadley, lead author of the report. “Not only does Georgia have the chance to reduce the number of uninsured adults overall, but it has a significant opportunity to bring down the uninsured rate in small towns and rural areas and narrow the gap between metro and rural areas.”