This article is reprinted with permission from Rural Health Quarterly

When Laurie* moved to rural western Colorado, she thought she had found a tranquil oasis to rest and die. Then 32, she was sober and living with HIV, but her health was waning and the mid-1990s HIV medications were taking a toll on her body.

“I moved to this area at a time in my life when I was dying, and wanted to move to an area that wasn’t busy or fast-paced, and a lot slower than what I was used to,” she said.

She couldn’t find a nearby doctor willing to take an HIV case, so she photographed spots on her body and sent them to her old specialist at Johns Hopkins University. He diagnosed her symptoms remotely via dial-up Internet.

But Laurie survived. She found an HIV doctor 250 miles away. But while her physical health began to improve through the trips across the state, her mental health spiraled. She was far from home, and her new, sparsely populated community was devoid of the support groups she had come to rely upon on the East Coast.

There were no affordable mental health resources, she struggled to find addiction recovery support, and her tenuous Internet connection didn’t accommodate online social networking with other people living with HIV. She felt hopeless, questioned the point of all the HIV activism she had championed through the decade and began to self-medicate with alcohol, after seven years sober.

“I was the girl who put ashes on the White House lawn and chanted in front of the FDA,” she said of her activist days. As much as the move to a more tranquil place was helpful to living longer, she lamented being removed from a supportive community. “When I moved here, it was completely different,” she said.

That’s where Project Alliance, as it came to be known, came in. A team of researchers set out to identify and test barriers to mental health care among people living with HIV in rural areas. A team of psychotherapists wanted to bridge those barriers — limited resources, transportation and connectivity issues — with telephone-based interpersonal therapy.

Depression is the most common psychiatric disorder associated with people living with HIV, and those in rural areas are 1.3 times more likely to be depressed than their urban counterparts and less likely to access regular mental health care, according to Timothy Heckman, lead author of the group’s latest project.

Their most recent work at the University of Georgia’s College of Public Health builds upon years of research, and found that teletherapy effectively reduces depression for people living with HIV in rural areas, over the long term.

“In people living with HIV, having a greater number of depressive symptoms is associated with more impaired daily functioning, poor engagement and retention in care, greater rates of risky sex, poorer adherence to antiretroviral therapy, and more comorbid [additional] health conditions,” Heckman said. “Obviously, all of these are important reasons to reduce depression in [this group] but, equally important, we just want to provide them with a chance to lead happier and healthier lives.”

The study was relatively small, with 147 participants from rural areas across 28 states, but found that after nine hour-long weekly sessions, acute depressive symptoms were reduced, and that reduction persisted after four- and eight-month follow-ups. Using a randomized control group that received standard in-person therapy, the teletherapy recipients were also less likely to use crisis hotlines and had fewer overall health care visits for emotional or substance-use support, according to the study.

Though the study showed statistically significant depression reduction in this unique population, it was also the first controlled study to show long-term teletherapy efficacy in any clinical population, signaling to researchers that more needs to be done in this area.

For Laurie, the phone-administered nature of the therapy was an important aspect. Not only did it mean she could enjoy the view from her deck during the session and not have to worry about driving to the next town to get services, it also gave her a veil of anonymity that she had never experienced in her community.

“It allowed me to talk about things that I wasn’t willing to talk about with other therapists and I looked forward to talking to someone who was understanding of my experiences, or at least willing to listen,” Laurie said. “I grieved [because] that relationship ending, but it was for a study and I knew I’d have to tell my story all over again to someone else.”

Though HIV cases still cluster in urban areas, it’s mostly rural states that are driving the epidemic. While the South is home to 38 percent of the nation’s population, it comprises more than half of new HIV cases, according to the CDC. This stretch of mostly rural areas also sees higher rates of poor and uninsured people, but most of the region’s states have not expanded Medicaid through the Affordable Care Act.

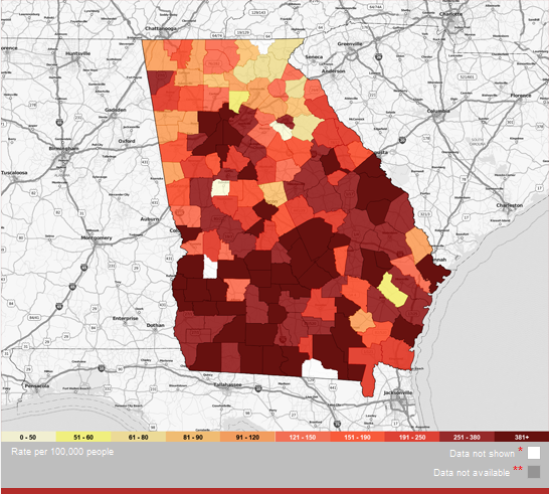

Of the 37,600 new national cases in 2014, Southern states have the highest proportion in rural or suburban areas, at 23 percent. The most recent data from the CDC pinpoint Georgia as the hub of new HIV diagnoses, with many of those in metro Atlanta. Just edging out Louisiana, Georgia had almost 32 new diagnoses per 100,000 people in 2016, and 1.5 more cases overall than the national average.

Though rates have gone down in recent years, black Americans are disproportionately diagnosed with HIV across the nation, especially in the rural South. In the nation overall, blacks account for 44 percent of new diagnoses, but only 12 percent of the population. Blacks account for 69 percent of new diagnoses in Georgia, though they are about 32 percent of the population. After metro Atlanta, the southern, more rural half of the state sees the next highest rates of cases.

To address the unique challenges of HIV in rural Georgia — including a network of 159 counties and swaths of remote land without paved roads or hospital access — the state health department has been expanding its telemedicine infrastructure for both behavioral and specialist care over the last decade.

Almost all the state’s health districts offer telemedicine hubs, and every county has a HIPPA-secure endpoint unit to connect patients remotely to the hub. Districts are big — covering up to 14 generally rural counties and encompassing more than 6,000 square miles. Patients have to be seen in person for at least the first visit if they want to access remote sessions from their county unit afterward.

Twelve counties have HIV-specific telemedicine units, which spreads out to about one per district outside of metro Atlanta. As of 2016, 45 behavioral health providers offered state-sponsored mental telehealth services.

Dr. Gregory Felzien previously led the HIV program in the southeast Georgia, and found himself spending upwards of 70 percent of his time traveling just to get to patients. Now, as director of the Department of Public Health’s entire HIV program, he says HIV-specific telemedicine has changed the way he gives and care and how patients receive it.

“Telemedicine has expanded the capability of specialists in touching a greater number of lives throughout rural communities,” Dr. Felzien said. After using telemedicine for almost a decade now, remote sessions allow more visits with reduced doctor and patient travel times, but better yet, he says, keep patients at their medical home where they are comfortable and have built relationships.

Dr. Felzien is concerned, though, about maintaining a sufficient workforce that can care for people living with HIV as they age into an older cohort.

“In meeting the needs of this population, we must focus on provider recruitment, increase training and HIV awareness, retain providers within the HIV workforce and focus on strengthening wrap-around services for patients through greater community collaboration,” he said.

Laurie, now 53 and with an undetectable viral load, worries too — both for herself, as she sees political forces threatening to chop the health benefits she relies on, and for her fellow HIV-positive Coloradans. She tried to start a local support group, but to no avail, and not because the disease isn’t there. It’s just invisible, she says.

“For long-term survivors … our wellness is fragile and it’s a scary time,” she said. “It’s not like I have a support group for people with HIV . . . but I do believe telemedicine has the mission of healing — it’s sad that it’s not developed more than it is, especially for rural places.”

*Last name omitted to protect medical privacy

Erica Hensley has written several articles for Georgia Health News. She is now a reporter for Mississippi Today.