Naoko Uno, with a pipette in one hand and quiet determination on her face, goes carefully about her work inside her laboratory at the University of Georgia’s Center for Vaccines and Immunology. Uno, a PhD student, and several others are working on a potential universal vaccine for dengue.

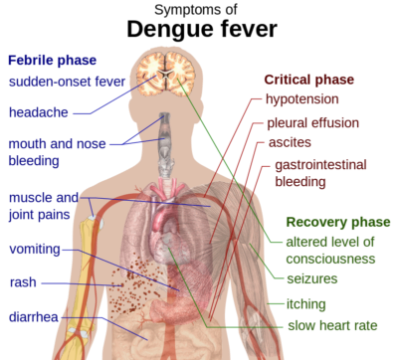

Dengue, often called dengue fever, is a mosquito-borne viral infection found mostly in tropical and subtropical countries. It causes flu-like symptoms and occasionally develops into lethal complications. More than a third of the world’s population lives in areas where there is a risk of infection, according to the CDC, and dengue is a leading cause of death and illness in areas where it flourishes.

Currently, there are few treatments or vaccines available for dengue. The main way to prevent infection is to avoid mosquito bites in high-risk areas.

This is where Uno’s research comes into the picture. Her lab is working on a vaccine using a technique called COBRA — computationally optimized broadly reactive antigen. They create the best possible consensus of known Dengue sequences to create a vaccine.

“From there, we test for immunological responses to the proteins in mice,” Uno said. “That enables us to characterize a more specific vaccine for the market.”

There are four serotypes, or distinct strains, of the dengue virus. A universal vaccine would protect against all four, and would be effective and safe in all age groups, regardless of whether or not an individual had been exposed to dengue in the past.

The state of the market

Effective dengue vaccines are not unknown, but they are rare. Only one has been approved and released, according to the World Health Organization (WHO). Several are still in the testing phase.

There are drawbacks with the current vaccines, and WHO recommends cautious use of them. They actually could increase the risk of severe dengue in people who have never had the disease, STAT News reported.

“WHO recommends vaccination only in individuals with a documented past dengue infection, either by a diagnostic test or by a documented medical history of past dengue illness,” the organization said in a statement released in December.

Most dengue vaccines are made from live, attenuated viruses. A universal vaccine, using an inactive particle, could give the universal dengue vaccine an edge in safety.

Generally, infection by one of the four dengue serotypes has been shown to confer lasting protection against that particular serotype, but only transient protection against a secondary infection from a different serotype. Moreover, secondary infection is associated with an increased risk of severe disease, which can ultimately lead to hemorrhage and death.

The only solution to this problem is what’s known as a tetravalent vaccine, one that would confer immunity against all four serotypes.

“We are also trying to test the vaccine to understand or detect the danger of antibody-dependent enhancement that comes from a previous infection by the virus,” Uno said. “In doing so, we have formulated a tetravalent vaccine.”

The lab has started with initial testing in mice. It the vaccine is validated to be effective and safe in certain research categories, the next step would be testing in non-human primates.

“Vaccine development can take decades, and with the recent controversy of Dengvaxia, there will be more stringent requirements prior to approval,” Uno said. Dengvaxia, one name for the currently approved dengue vaccine, has caused an uproar in the Philippines over its effects on previously uninfected people.

“. . . With our vaccine, we deliver the vaccine right now in the form of sub-viral particles, primarily a protein shell” Uno said. The particle looks like the virus on the outside but has no genomic material inside, so it cannot infect or propagate in the human body. Therefore, it is safer since it won’t cause an unwanted immune reaction like Dengvaxia.”

Dengue in America

There are several tropical areas under U.S. jurisdiction — including Puerto Rico, the U.S. Virgin Islands, American Samoa and Guam — where the virus is endemic. And the threat to the main part of the country can’t be ruled out entirely, since Aedes aegypti, the mosquito that transmits dengue to humans, is commonly found in several U.S. states.

Still, according to the CDC, most reports of dengue in the United States turn out to be travel-related, meaning the people became infected while they were abroad, not at home. The disease is generally very rare here.

“The typical ‘American’ lifestyle helps reduce the threat of dengue in the U.S.,” said Dr. Melinda Brindley, a University of Georgia researcher who researches dengue transmission in mosquitoes. Most homes have window screens and air conditioning, which helps reduce the number of mosquitoes inside.

“The Aedes mosquitoes that transmit are day biters, and most Americans stay inside for most of the day, decreasing mosquito exposure,” she said. “We also live in areas with low mosquito densities, and people are also spread out more — this decreases the likelihood of large outbreaks in the U.S.”

In addition, mosquito control agencies monitor mosquito populations and spray insecticides to reduce them. And city, county and state governments are mostly doing a decent job of informing the public about mosquito outbreak concerns, Brindley added.

“In general,” she said, “I think the U.S. would be able to organize efforts to slow and stop the spread of a dengue outbreak, provided the government provides the funds needed – similar to the funds used to help during the Zika outbreaks” that affected some Americans in 2016.

Meanwhile, climate change is affecting the transmission of vector-borne diseases such as dengue, Zika, Chikungunya and more. As temperatures warm in some areas, warm-weather diseases can spread, though that has happened only incrementally so far.

“Since climate change is typified by the rise in global temperatures, early predictions suggesting massive increases in vector-borne diseases have fortunately not been realized,” said Dr. Courtney Murdock, a University of Georgia scientist who works on vector-borne disease transmission.

Prajakta Dhapte is a graduate student in the Health and Medical journalism program at the University of Georgia with a special interest in science communication. She has a bachelor’s degree in biotechnology and a master’s degree in virology from the National Institute of Virology in India.