Georgia improved by one spot, reaching No. 40 in an annual ranking of states’ health systems, released Thursday.

The state’s ranking in the Commonwealth Fund report is similar to the results on other national scorecards in health care. Georgia was ranked 41st last year in the State Health System Performance scorecard and 46th in the previous ranking.

Georgia’s top-ranked health indicators in the report included high vaccination rates for young children; a comparatively low rate of deaths from suicide, alcohol, and drug use; and a high rate of diabetic adults getting a blood sugar test.

The state, though, received low rankings on bloodstream infections from central-line catheters; people going without care due to cost; and children who did not receive the mental health care they needed.

Georgia was 47th in both infant mortality and adults who are obese. (Here’s a link to the report.)

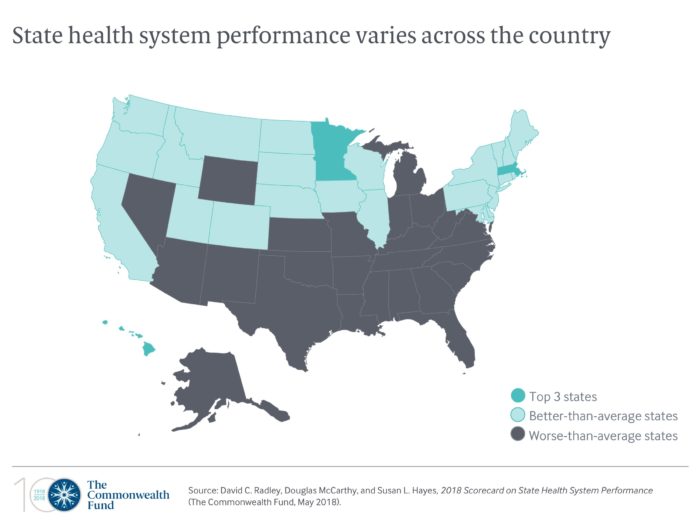

Several states in the South or on its periphery were clustered low in the rankings, with Mississippi at the bottom. They were South Carolina, at 38th; Tennessee, tied with Georgia for 40th; Kentucky, 42nd; Texas, tied for 44th; Arkansas, tied for 46th; Florida, 48th; Louisiana, 49th.

“The low ranking of Georgia reflects the high number of people who are uninsured in Georgia without access to health care, particularly preventive care,’’ said Marsha Davis of the University of Georgia’s College of Public Health, responding to the rankings. “The high numbers of infants who die and children who are without mental health care in Georgia are staggering.’’

Georgia’s uninsured rate, at about 13 percent, is among the highest in the country. (Here’s a GHN article this week on the expected increase in the uninsured rate.)

The state ranked 51st in children’s mental health services in the report. This year, though, Gov. Nathan Deal’s budget included more than $20 million in additional funding for various services for children’s mental health and substance abuse, based on the recommendations of a gubernatorial task force.

Nationally, the Commonwealth Fund report said the combined death rate from suicide, alcohol, opioids, and other drugs increased by 50 percent from 2005 to 2016. Rates rose across all states and were up at least twofold in Delaware, Ohio, New Hampshire, New York and West Virginia.

This week, the Atlanta Regional Commission reported that the rate of opioid-related overdose deaths in metro Atlanta in 2016 was nearly double the rate in 2013 and more than three times the rate in 2006.

Neil Campbell of the Georgia Council on Substance Abuse said this week that the increase in synthetic opioids, the ability to purchase drugs made outside of the country via the Internet, and heroin being combined with dangerous drugs “has helped lead us to where we are.”

She also cited past budget cuts in prevention and treatment services.

The good news, Campbell said, is that Georgia has received about $11.8 million in federal funding to deal with the opioid crisis. She noted that in combating the epidemic, the state has funded a recovery support line; recovery coaches in emergency rooms; and distribution of the overdose reversal drug naloxone.

“We have a long way to go, but hopefully we will start to see the effects of these strategies quickly,” she said.

Poverty is a key factor in low health rankings of Southern states, said Solveig Cunningham of Emory’s Rollins School of Public Health.

That affects access to care. Cunningham cited the report finding that in Alabama, low-income adults were nearly seven times more likely than those with higher incomes to skip necessary care because of costs (33 percent vs. 5 percent). But in Pennsylvania, the disparity between high-income and low-income adults was much less (17% vs. 9%).

Southern states tend to have a greater chronic disease burden, with higher rates of stroke, obesity and diabetes, Cunningham said. “We tend to see blacks do worse [on health measures] than whites in the South, and whites do worse in the South than whites elsewhere.”

The Commonwealth Fund report is useful in showing that states that put financial resources into improving a health indicator can show positive results, Cunningham said. And it gives researchers and policymakers a good reference point on the challenges a state faces, she added.

Nationally, the Commonwealth Fund report said:

** Premature deaths are on the rise, with the rate of deaths from treatable medical conditions up nationally and in two-thirds of states in 2014–15.

** Gaps in mental health care are pervasive. Across states, 41 percent to 66 percent of adults with symptoms of a mental illness received no treatment between 2013 and 2015. Up to one-third of children needing mental health treatment did not receive it, according to parents’ reports in 2016.

** Those states ranked highest — Hawaii, Massachusetts, Minnesota, Vermont, and Utah — performed about twice as well, on average, than the lowest-ranked — West Virginia, Florida, Louisiana, Oklahoma, and Mississippi.

And in general, the scorecard found substantial improvement in people’s overall ability to get and afford health care. States that expanded eligibility for Medicaid, as encouraged by the Affordable Care Act, saw the biggest declines in their rates of uninsured people and cost-related barriers to care.

Georgia and most of the low-ranked Southern states have opted not to expand Medicaid.

UGA’s Davis said the report “highlights the need for policymakers in Georgia to consider the benefits of Medicaid expansion to promote equal access to health care.

“The report also highlights the health disparities we see by region of the state, income, and ethnicity,’’ Davis said. “Improving the health of all Georgians will require coordination of efforts across multiple sectors and services.”