PART TWO OF A SPECIAL REPORT

By Brenda Goodman, Andy Miller, Erica Hensley, and Elizabeth Fite

Brenda Goodman is a senior news writer for WebMD and Andy Miller is editor and CEO of Georgia Health News. Freelance writers Erica Hensley and Elizabeth Fite also contributed to this report. This investigation was supported by a grant from the Arthur M. Blank Family Foundation.

Many older cities used lead pipes to deliver water to homes.

These pipes —known as service lines— became infamous after their role in the Flint, Mich., water disaster.

Getting water through these pipes is like sipping water through a straw made of pure lead. They are considered by the EPA to be the greatest lead hazard to drinking water.

Lead can cause irreversible damage to the brain and other organs of young children.

The problem is that many utilities have lost track of where their lead service lines are, and they aren’t actively looking for them.

Last year, a national survey of water utilities estimated that Georgia could have as many 86,000 lead service lines. Even state regulators charged with protecting the public from high levels of lead in water don’t know where they are.

“We do not keep records on the number or locations of lead service lines in the state,” said Kevin Chambers, communications director for the Georgia Environmental Protection Division, in an email.

Our investigation uncovered some clues to where these dangerous pipes might be.

We reviewed water records for more than 100 water systems in the state. Five water systems had records showing they had lead service lines:

** Athens-Clarke County

** Demorest

** Perry

** Richmond Hill

** Statesboro

Statesboro and Athens confirmed that their records were correct. The others say their records are wrong, and that they don’t believe they’ve ever had any lead service lines.

“I have personally dug up lines in these neighborhoods, and by and large they are all PVC service lines,” said Charles Heino, director of municipal operations for the Richmond Hill water system in Southeast Georgia. “I have yet to dig up a [lead] gooseneck or lead service line; but that’s not to say they can’t exist; I simply cannot verify it with my own experience,” said Heino.

In Statesboro, where water records show testing addresses have lead service lines, Van Collins, assistant director of water and wastewater, confirmed that the records are correct. “We sure do have them in the older parts of town,” he said, when we asked about his records.

Cities rediscover their lead pipes

Tom Neltner, an attorney and chemicals policy director with the Environmental Defense Fund, says it’s not uncommon for water systems to think they don’t have lead service lines.

“The state of Washington swore… they always said, ‘we don’t have any lead service lines,’ then they started finding them as Flint came out and people started paying attention,” Neltner says.

In May 2016, Washington Gov. Jay Inslee directed water utilities to look for lead pipes in their water systems. As of February, they’ve found more than 7,500 lead pipes through a voluntary survey. “They found them in Tacoma, Seattle, and Spokane,” says Neltner, who is a founding member of the Lead Service Line Replacement Collaborative, a group of 23 organizations that are working to encourage water utilities to find and replace their lead service lines.

The Environmental Defense Fund recently graded all 50 states on their lead pipe disclosure policies. Georgia was one of 12 states that got an F, because the state doesn’t require water systems to tell customers if they have lead pipes.

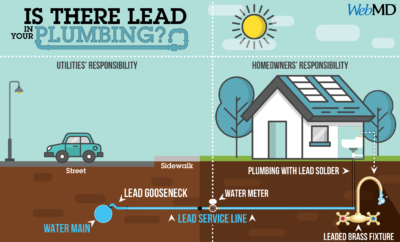

In Georgia, the part of the service line that runs between the water meter and the house is considered to be the homeowner’s property. Many water utilities told us they don’t feel they should be responsible for pipes they don’t own—a position that was recently stated by the National Rural Water Association in a letter to the EPA.

“The property owner has to assume responsibility for his/her infrastructure,” the letter reads.

The problem is that water utilities originally installed service lines to homes, and many kept records on the kinds of materials that were used to do it. So water utilities are in the best position to inform the public about where lead pipes are.

Yet many water systems say those records have been lost.

“There’s no public water system that has such bad records they don’t know if they have a lead pipe or not,” says Marc Edwards, PhD, professor of civil and environmental engineering at Virginia Tech in Blacksburg.

Atlanta’s history of lead in plumbing

What about Georgia’s capital, Atlanta?

In the early 1900s, historical records show Atlanta was one of the 50 most populous cities in the U.S. using lead service lines.

The city has been telling customers and regulators for years that those pipes are all gone.

Given that many cities across the U.S. are only just now rediscovering how many lead pipes are still in their water systems, we wanted to know how Atlanta could be sure that was still true.

At first, the city didn’t answer that question.

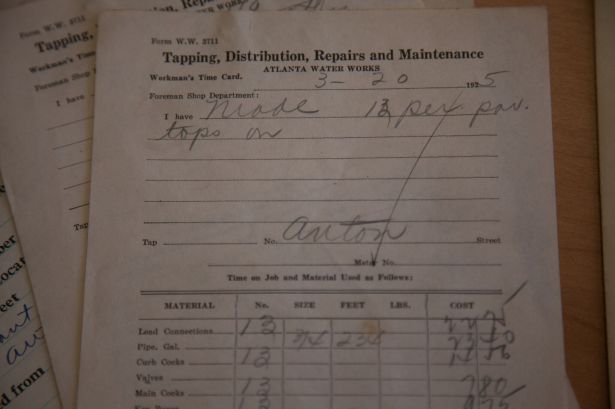

So we did a little digging. We filed an Open Records Request for records called tap cards.

Workers for the water department filled out these forms when they connected homes to the city’s water. They list the materials used to “tap,” or connect, a house to the main water pipe in the street.

Around the country, records like these are helping water utilities find the old lead pipes they still have. Boston, Tacoma, Washington, D.C., and Flint, Mich., have used tap cards to create maps so residents can find out if their home might get water through lead pipes. Ohio even passed a law last year that requires water systems to find and map their lead pipes.

After a couple of tries, the Atlanta Department of Watershed Management re-discovered their tap cards. Now yellowed and brittle with age, they are handwritten, in pencil.

At the top of the list of materials used to build these taps: Lead.

One record shows there were 13 homes attached with “lead connections” on Anton Street in 1925, for example. There were 19 homes attached with lead connections on Arlington Place in 1922, according to another record. We found examples of these records dating to the 1940s.

We asked plumbing experts what “lead connection” might refer to.

“It’s usually a gooseneck,” says Scott Murphy, a project manager for ESG Operations, a company that runs municipal water systems across the state. “It’s about a 2-foot section of tubing that connects that water main to the pipe that goes to the house.”

Water departments used these s-shaped pipes, Murphy says, because they could be easily bent to direct the service line to the house. Murphy says he still occasionally runs across them on jobs. When he finds these lead goosenecks, he replaces them.

Typically cities didn’t have a coordinated plan to remove goosenecks or any other kinds of lead pipes. Some have been replaced over the years when they’ve leaked, or when workers have run across them in the course of road repairs.

In 2016, Atlanta told its water customers in a water quality report that “The City of Atlanta has no lead service lines, but does have some lead joints.”

After we pressed city officials about the tap cards, their story changed.

“Lead service lines may still exist in some older areas of the city,” says Cameo Garrett, external communications manager for the City of Atlanta in an email, but they should amount “to less than 1 percent of the total length of pipe in the Atlanta Water Distribution System.”

Garrett says the city had a lead pipe replacement program in the 1980s. As the city replaced lead water mains, it also replaced the lead service lines connected to them, she says, but they can’t be sure they’re all gone, especially in the older parts of the city.

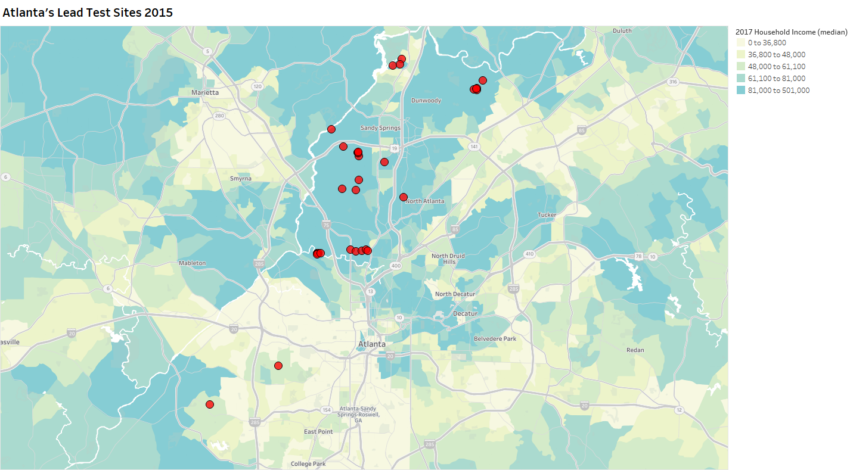

Atlanta’s Water Department, however, is generally not testing for lead in the older parts of the city—where they say lead service lines could still exist.

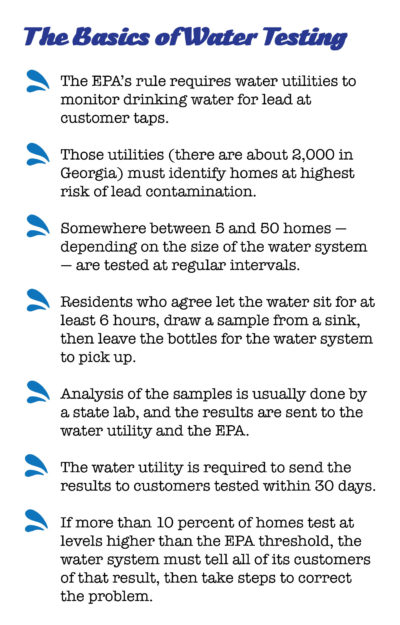

The EPA’s Lead and Copper Rule for monitoring lead in water calls on utilities to test homes with lead service lines before any other kinds of sites are used.

But under that Rule, if a utility claims they don’t have any lead service lines in their service area, they can move to a different kind of high-risk home — houses with copper pipes and lead solder installed between 1982 and 1988 — and still satisfy testing requirements.

In 2015, most of the homes Atlanta tested were in the affluent northern areas—Brookhaven, Buckhead, Sandy Springs, and Dunwoody. A check of the test addresses revealed most of those homes were built in the 1980s.

When asked how they choose homes for lead testing, Garrett said in an email that the city follows criteria set out in EPA guidelines. Sites in downtown or older neighborhoods may not meet this criteria, she said.

Atlanta’s current lead testing strategy troubled one local health expert.

Harry Heiman, MD, of the Morehouse School of Medicine, an expert on health disparities, says neighborhood conditions play a major role in our health, leading to the recognition that zip code is a more important predictor of health than one’s genetic code.

“The map you shared suggests that home surveillance is operating with either a blind eye or intentional disregard to ensuring protection of low-income minority communities,’’ says Heiman. “The areas in which homes are being tested appear to be disproportionately white and more affluent; those not being sampled, disproportionately in low-income minority communities,” says Heiman, referring to lower-income neighborhoods on Atlanta’s south and southwest sides.

Another local water expert says now that the city has acknowledged its lead pipes, they should work to get them out of the water system.

“I am not surprised that a water system as old as Atlanta’s still has lead in network,’’ says Chris Manganiello, water policy director for the Chattahoochee Riverkeeper. “Ideally, the city would identify and prioritize replacement. To ease any public health concerns, the city could offer to test the water in older areas where lead materials are identified.”

COMING WEDNESDAY: Her home showed high lead; she wasn’t told

PART ONE: Lax oversight dilutes impact of testing water for lead (Here’s the link)

SOURCES:

Kevin Chambers, communications director, Georgia Environmental Protection Division, Atlanta, Ga.

Charles Heino, director of municipal operations, Richmond Hill Water System, Richmond Hill, Ga.

Van Collins, assistant director of water and wastewater, City of Statesboro, Statesboro, Ga.

Tom Neltner, chemicals policy director, Environmental Defense Fund, Washington, D.C.

Marc Edwards, PhD, professor, Civil and Environmental Engineering, Virginia Tech, Blacksburg, Va.

Scott Murphy, project manager, ESG Operations, Macon, Ga.

Cameo Garrett, external communications manager, City of Atlanta, Atlanta, Ga.

Harry Heiman, MD, director of health policy, Satcher Health Leadership Institute, Morehouse School of Medicine, Atlanta, Ga.

Chris Manganiello, water policy director, Chattahoochee Riverkeeper, Atlanta, Ga.

Lead Testing Records for 105 water systems, obtained through a Georgia Open Records Act request.

Tap cards for the City of Atlanta water system, obtained through a Georgia Open Records Act Request.