Surgeon and bestselling author Atul Gawande writes that he never learned about mortality in medical school. He learned to examine, prescribe and operate, but not how to help patients die well.

It wasn’t until he was a practicing surgeon that he confronted the idea of a “good” death — a death consistent with a life fully lived. A death that lets the patient be surrounded by family and friends, instead of by doctors and humming medical machines. A death that is calm, soft and warm, instead of chaotic, mechanical and cold.

That sounds good, but it is not the death that most Americans experience.

Fewer than one-third of Medicare beneficiaries actually die at home, although 90 percent told Kaiser Family Foundation that this was their preference. And fewer than half of Medicare patients use the hospice benefit they’re entitled to.

In Home Hospice Care is a Medicare benefit that provides nursing, counseling and pain management, known as palliative care, usually in patients’ homes. Aiming to provide quality of life in a comfortable setting, hospice services offer coordinated care rarely seen in other medical contexts — but only to patients who have six months or less to live as determined by their doctor.

The costs of the care are covered for eligible patients, with the hospice provider billing either Medicare or private insurers, and the services are delivered right to the doorstep.

“It’s like wearing a life preserver,” said Martha Sweat of Athens.

Her husband, Ricky Sweat, signed up for hospice care in August, shortly after he was told he had amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, or Lou Gehrig’s disease, at the age of 60. Since both Sweats were under 65, they didn’t qualify for Medicare, but their private insurance covered the hospice bills.

Ricky’s disease progressed rapidly. And this week, he passed away where he wanted to be – at home.

Earlier, Martha said they couldn’t have coped on their own, and that it was just the two of them at home when Ricky breathed his last.

During an interview in October, Ricky said through a text that he had consented to hospice care to ease his wife’s burden and worry. He had lost his voice and the movement of his legs and right hand early in the course of the disease, and thereafter communicated by signing or by typing with his left hand on his iPhone.

The couple received regular help from an in-home hospice program run by Athens-based St. Mary’s Health Care System. A nurse, a social worker and two aides made weekly visits. Ricky’s nurse helped with his pain management medicines, and aides helped him bathe and eat as his physical abilities deteriorated.

“I get so much comfort just knowing I’m not alone,” said Martha. From the weekly visits by hospice personnel, to knowing she could call the hospice line 24/7 for emergency help, the support was both physical and emotional for her and Ricky.

Patients take different views

Terminally ill patients who don’t opt for hospice are more likely to die in a hospital, undergoing one treatment after another even when improvement is unlikely. Families sometimes feel powerless to say no to additional procedures or medications, and they often watch helplessly as treatment becomes futile and their loved one is in pain, said Jean Andrews, a certified hospice and palliative care nurse and RN case manager at Hospice Compassus in Athens.

Palliative nurses are experts at noticing and managing pain during life’s final chapter.

“You can always tell the amount of pain someone is in by how furrowed their brow is,” said Andrews. Watching the patient and the patient’s family, and picking up on non-verbal signs as well as words, tell her when more pain medication is needed and whether everyone is in sync as death approaches.

Andrews, who has been a nurse for two decades, founded the palliative care program at Athens Regional Medical Center, now known as Piedmont Athens Regional, in 2005. Over eight years, she counseled 6,000 patients and families about end-of-life planning and ensuring as good a death as possible.

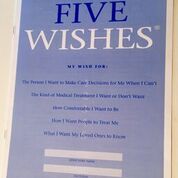

Education about end-of-life options, including advance directives, is a big part of a palliative nurse’s job, said Andrews. Georgia’s advance directive form walks patients and family members through various end-of-life scenarios and lays out the options available, including palliative care and hospice. Once the paperwork is filled out, copies should be filed with doctors and family members, and stored in a safe place at home so paramedics and family members can find patients’ directions

As Atul Gawande and others have observed, doctors are trained to be warriors, to “beat cancer” or “fight disease,” and that gives them an activist mindset. When Andrews started the palliative care program at Piedmont Athens Regional, many doctors and other medical staffers weren’t in the habit of talking about palliative or hospice care, and patients didn’t know to ask. Talking about hospice was nearly taboo among the hospital personnel, as if that would be a betrayal of their mission.

[youtube]https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_COE0oyppFw&list=PLjZwvuEsYdlwZunKHR7tlxzKhslXbo0_q[/youtube]“People falsely equate hospice with dying because for years, hospice was recommended too late and it was essentially a death sentence,” said Andrews. Connecting patients with hospice care earlier, when they have time to reap the quality-of-life rewards is key, she said.

But the time is still limited. Ricky’s nearly four-month hospice stint is rare for the service, which usually sees shorter stays. In 2013, 35 percent of patients spent less then a week in hospice; only 21 percent were in such programs for longer than three months, according to the National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization.

Once a person enters hospice care, treatments aimed at a cure are stopped, and the focus shifts to easing pain and promoting comfort. Palliative care replaces curative treatment with comfort.

Andrews talked frankly with patients about the differences and encouraged candid conversations about the burdens and benefits of continued treatment. For example, she asked, “What’s important to you in your own end-of-life care and where do you see yourself dying?” If questions like this go unasked and unanswered, the patient’s idea of a good death may not be honored.

Some patients and families push back against end-of-life consultations with providers, Andrews said. These people don’t want to “give up” and accept hospice care, because they’re not ready to stop standard treatment.

Others, like Ricky and Martha Sweat, have different ideas. When he became terminally ill, they saw home hospice care as their best option.

Martha said she and her husband both realized that a cure was not in the cards for him. “But we wanted help with managing the disease and improving our quality of life,” she said. “And [hospice] came just at the right time for us.”

Martha used a lift to help Ricky in and out of bed and into his chair, and she gave him daily liquid meals though a feeding tube. Sometimes she helped him get outside to enjoy the fresh air. She played the piano for him and helped arrange visits from relatives and friends when the couple were feeling up to it.

In-home hospice services, she said, gave them both the quality of life they wanted and the comfort they needed to face the end of Ricky’s life.

Erica Hensley is a health and medical journalism graduate student at UGA’s Grady College of Journalism and Mass Communication. She graduated from the University of Southern California in 2008 with degrees in political science and print journalism, then freelanced and managed an independent bookstore in Atlanta before pursuing a master’s degree to focus on disparities in mental health care resources.