This week, Emmanuel Ellison celebrated a “birthday” that mattered more to him than the real 40th birthday that he will celebrate in May.

April 12 marked three years of sobriety for Ellison after decades of heavy drinking, committing petty crimes and felonies, and experiencing unexplained extremes in mood and energy, which he now knows were caused by untreated bipolar disorder.

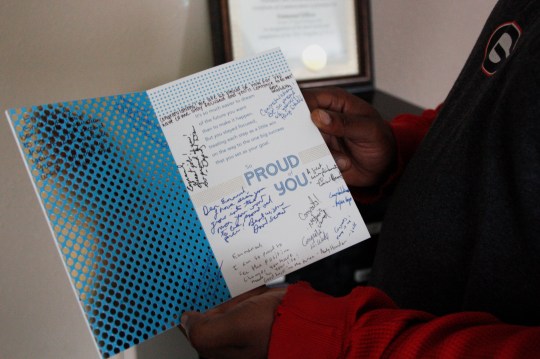

Ellison credits the Athens Treatment and Accountability Court, or TAC, with his sobriety and his new life. He and four other people, all diagnosed with serious mental health disorders, graduated from the program in February. Ellison immediately framed his diploma and hung it on the living room wall of his East Athens duplex apartment.

[youtube]https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qKj-0H-d2r8[/youtube]TAC and other mental health courts aim to keep mentally ill repeat offenders out of Georgia’s prisons and jails, which are notoriously ill-equipped to help them.

Georgia Gov. Nathan Deal and many state legislators back the expansion of these special courts as a type of criminal justice reform that improves public safety and shrinks tax burdens.

There are now 31 mental health courts in the state, making Georgia among the leading states for these courts. The Athens TAC handles 30 cases now, and statewide the programs keep more than 500 people out of costly jails and prisons.

Breaking a self-destructive pattern

Like many TAC clients, Ellison came from a family with a chaotic lifestyle and abusive father. He left home at a young age, bouncing around unstable Athens neighborhoods. He began drinking and didn’t return home.

He cycled in and out of local jails and state prisons. He was sober when he was behind bars but still was saddled with up-and-down psychotic symptoms. He knew he needed help but didn’t know where to turn.

Every release from jail was a harder adjustment than the last, Ellison said. “I couldn’t adapt to society because my anger and paranoia took such a toll.”

More than half of state inmates suffer from mental health problems, according to the U.S. Justice Department. Jails and prisons have become de facto mental health hospitals.

Ellison’s luck changed in late 2012, when he faced an aggravated battery charge. He was assigned a public defender who thought TAC would be better than another regular trial and more jail time.

Ellison was skeptical at first but agreed to an evaluation with social worker Elisa Zarate, who coordinates the Athens TAC. His rap sheet and initial mental health assessment made him a likely candidate.

In early 2013, Ellison was examined by psychiatric professionals at Athens-based Advantage Behavioral Health, the mental health contractor for the accountability court. They diagnosed him with bipolar disorder and alcohol use disorder, a dual diagnosis that fits about half of TAC participants.

Advantage developed an individual treatment plan that required Ellison to keep regular psychiatry and addiction treatment appointments, participate in cognitive and social skill classes and show up for weekly meetings with court staff.

TAC requires people to stay in treatment for at least 18 months, but judges can extend the timeline throughout an individuals’ probation period if necessary.

Ellison had a rocky start. He didn’t feel that he deserved to be in the program and was ashamed of his past behavior. He also clashed with TAC’s strict schedule, missed appointments and took up drinking again. He told the team and Judge David Sweat, who presides over the court, that he needed more help.

“I didn’t change my environment at the beginning,” he said. “And I hadn’t learned to trust yet.”

After his relapse, the court sent Ellison away for 30 days of mandatory residential care. Every day during his stay, he met with a psychiatrist and participated in group therapy. By the time Ellison left, he was stabilized on a three-drug regimen. He’s been sober ever since.

Zarate and case manager Kristen Daniel are on call for problems, and they know that time is the great healer. Ellison takes three prescription medicines — for bipolar disorder, depression and insomnia.

Getting off the streets is also key to normalizing life. “We want them to be accountable and compliant with their probation and treatment, but before we can expect them to do that, we have to help make sure they have a roof over their head and have food,” Zarate said.

During his time in TAC, Ellison’s mom offered him a place to live with her as long as he stayed sober. He said her no-nonsense attitude kept him on the path to recovery and helped him maintain the schedule set by Judge Sweat.

Ellison keeps an early bedtime and also gets up early. He prays and lifts weights every day at 7 a.m. — disciplined habits fostered by TAC’s morning check-ins and evening curfews.

All this helped Ellison re-enter regular life, and so did forging personal ties with Daniel and Judge Sweat.

But there was a setback.

About two years in the program, Ellison was in a car crash that severely injured his back and killed his younger brother. He still deals with the legal, medical and emotional ramifications of the wreck. TAC helped him work through a tragedy that would have derailed him just a few years earlier, he said.

Since then, Daniel has helped Ellison qualify for Social Security disability benefits, which allowed him to get his own apartment.

Ellison leads a simple life now — and one that makes him proud. He walks often, both for exercise and meditation. He picks up medicine for his mom and plays basketball with his grandsons. Talking about his family makes him teary-eyed, with hopes that he’s counteracting the abuse and stress imposed years ago by his father. Ellison says he’s still getting accustomed to being a comfort for his daughters instead of a constant source of worry.

“Every day I wake up, and it gets easier,” he said. “And I feel good.”

Legally, Ellison is still on probation and meets monthly with his probation officer. He goes to meetings to stay sober and remain connected to TAC participants and staff.

“With Emmanuel’s case, he knew that he had people that he could call and talk to and that he trusted,” Daniel said. “It really made the difference for him.”

Seeking to help more people

Navigating the criminal justice system is tough for anyone, and especially hard for those who struggle with mental health and substance use disorders. Repeat offenders with these burdens often lose hope and feel powerless.

“Support groups and skill classes give their power back to them,” Daniel said.

Mental health policy advocates say expanding accountability courts can divert people with mental illness into treatment and rehabilitation and reduce the crowding of jails and prisons.

Some critics, however, say the effectiveness of courts such as TAC has not been scientifically proven.

With those concerns in mind, Zarate is seeking funds to pay for a formal evaluation of TAC by qualified researchers. A positive evaluation could pave the way for more slots in the program for people who need help.

Ellison is glad he got his chance. “It’s on you if you want to succeed or not,” he said. “They give you that responsibility and they teach you how to believe in yourself.”

Erica Hensley is a health and medical journalism graduate student at UGA’s Grady College of Journalism and Mass Communication. She graduated from the University of Southern California in 2008 with degrees in political science and print journalism, then freelanced and managed an independent bookstore in Atlanta before pursuing a master’s degree to focus on disparities in mental health care resources.