There wasn’t much buzz around Clay “Bear” Kelley’s beehives last year.

The longtime beekeeper lost most of his honeybees to hordes of bloodsucking mites and beetles that took root in his once thriving colonies.

“[The hive beetles] get in, and they eat up the honey and the brood,” said Kelley, owner of Bear’s Bees in Cordele and president of the Georgia Beekeepers’ Association. “Before you know it, they leave.”

The same strange phenomenon has played out in front of beekeepers across the country. During the winter of 2013-2014, the U.S. lost 23.2 percent of its managed honeybee colonies, according to an annual beekeeper survey conducted by the Bee Informed Partnership and the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

On average, the country has lost 29.6 percent of its managed colonies every winter since 2006.

This trend is an indirect but serious threat to the health of Georgians and others. If the honeybee die-offs continue, many nutritious crops that depend on the little critters for pollination, including many fruits and vegetables, could become scarce. In turn, these foods would become much more expensive, which is bad news for people who already struggle to afford a healthful diet.

The huge cost of losing pollinators

In a study published recently in the Journal of Entomology, researchers at the University of Georgia show just how much the Peach State could lose without the helpful honeybee.

“If we just waved a wand and got rid of all our pollinating insects, we predict a cost to our state’s economy of $367 million annually,” said Keith Delaplane, one of the authors of the study and director of UGA’s honeybee program.

“That would be lost, unrealized revenue,” said Delaplane, a professor at UGA’s College of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences.

The researchers looked at 55 fruits and vegetables eaten directly by humans. To some extent, all of the crops considered depend on honeybees for pollination, although they also rely on other pollinators like bumblebees, solitary bees and flies.

“But among the insects, bees are hands down the best pollinators,” Delaplane said.

Of all the crops in the study, watermelons, cantaloupes, pumpkins, winter squash and yellow squash were the most dependent on pollinators, and thus were more vulnerable to declines. Sweet Georgia peaches came in second, along with other fruits like apples, blueberries and cherries.

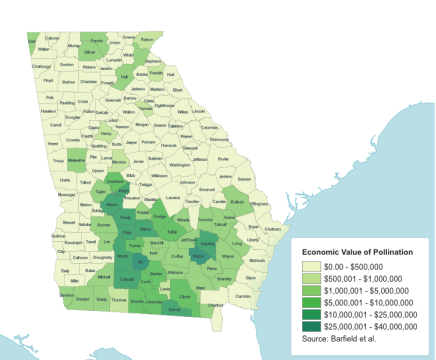

Georgia counties owe an average of $2.3 million to pollinators. Without the help of pollinating insects, many South Georgia counties would take a huge financial beating, with some potentially losing up to $10 million. One of these, Tift County, is especially vulnerable to pollinator decline, with an estimated $39 million in crop revenue dependent on pollination annually.

But counties with the most vulnerable crops are more dispersed throughout the state. The crops grown in Dade County, located in the state’s northwest, are especially vulnerable, with 89 percent of its crops reliant on insect pollination.

“So it’s not just a southern Georgia problem,” said Ashley Barfield, lead author of the study and a UGA Ph.D. student in agricultural and applied economics. “As far as individual farms facing impacts, it’s a whole Georgia problem.”

Why the surge in losses?

Honeybee populations have been dwindling to some extent since World War II, but they have “really taken a precipitous drop since the winter of 2006,” Delaplane said.

In 2006, beekeepers around the nation started reporting what’s now known as Colony Collapse Disorder (CCD), a syndrome characterized by the sudden and mysterious disappearance of both living and dead adult worker honeybees from the hive. So far, there have been no proven scientific explanations for CCD.

But CCD is only one of many blights threatening honeybee populations nationwide. Delaplane says three of the biggest contributors to the decline are Varroa mites, viruses and environmental toxins.

The mites damage the bee and compromise its immune system, making it vulnerable to diseases caused by viruses. These viral infections can lead to wing deformities, paralysis and death.

Chemicals found in certain pesticides have also been linked to bee deaths and CCD, while others can be poisonous when they come across other pesticides lingering in the environment. For example, an insecticide used to safely control mites in the hive can turn deadly when it encounters a fungicide that’s commonly used on watermelons.

“This is a huge problem,” Delaplane said. “And what’s so sobering is that’s just the one we’ve found. There is no way we can realistically discover every possible synergy that’s out there.”

Fortunately, even though honeybee numbers are decreasing, Delaplane said consumers are still not feeling the pinch, partly because other bees are picking up the slack.

“I see this heroic compensation by solitary bees and native bees,” Delaplane said. “[They can be] spotty, really strong in one farm and completely absent in another, but they’re really carrying the day on pollination.”

So far, he said, the declines in the honeybee population haven’t driven up the prices of food or pollination services that much.

“But we need to be in front of this wave so that doesn’t happen,” he said.

Hyacinth Empinado is a freelance journalist in Athens. She is currently pursuing a master’s degree in health and medical journalism at the University of Georgia.