More Georgia children should be screened for potentially dangerous levels of lead in their blood, public health officials say.

The testing is especially important for kids in higher-risk areas, says Chris Rustin, director of environmental health for the state Department of Public Health.

But children in those riskier areas are often are less likely to get lead testing than those in safer neighborhoods, he says.

Lead poisoning is particularly dangerous for children under age 6. It can cause central nervous system damage and intellectual and behavioral deficits, among other health effects.

“The neurological damage in some cases can be irreversible,’’ Rustin says.

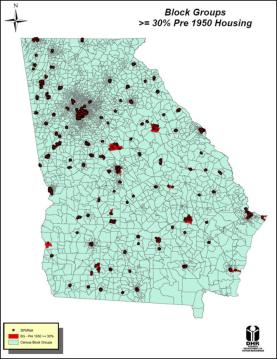

The most dangerous situations generally occur in homes built before 1978, which contain lead paint.

Some children in older houses “are picking up lead dust,’’ Rustin says. Children can ingest dust or paint chips or inhale lead particles. Other sources of lead include toys and imported pottery.

African-American children and kids living in poverty have a higher risk of lead exposure.

Public Health officials are working with Georgia pediatricians to publicize the importance of lead screening.

Medicaid rules require testing of young children for lead poisoning, but Georgia and other states appear to have large gaps in these screenings.

What’s high-risk?

Public Health lists the high-risk counties as Bibb, Carroll, Chatham, Cobb, Crisp, DeKalb, Dougherty, Fulton, Gwinnett, Hall, Laurens, Richmond, Whitfield and Ben Hill. It may seem a rather varied list, but what the counties have in common is a lot of older housing stock.

Among Georgia children tested, an estimated 3,000 to 5,000 are at “a level of concern,’’ with a blood lead level of more than 5 micrograms per deciliter, Rustin says. That’s the level where CDC recommends public health actions to clean up the problem.

Testing in high-risk areas, though, has lagged, state officials say.

How much testing of young children is being done is a difficult matter to nail down.

Lead screening is mandatory for Medicaid children at their 12- and 24-month preventive health visits and is reported to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services.

A CMS analysis indicated that about two-thirds of children enrolled in Medicaid were screened for lead during 2008–2009 despite the federal requirement.

Georgia’s Medicaid agency reports that for children in the 1-to-2 age range, 50.9 percent received a blood lead screening in federal fiscal year 2014.

Figures from the Department of Public Health put the testing figure a little lower for that age range, at 43 percent. Rustin places Georgia in the midrange among states for Medicaid blood testing, based on available data.

Jane Perkins, legal director of the National Health Law Program, says there are many reasons for poor performance by state Medicaid programs on lead screenings.

“Some primary care providers do not believe there is a problem with lead, and state Medicaid bulletins on the subject could provide Medicaid-participating providers with helpful education on this point,’’ Perkins says.

“Because they believe there is little risk from lead, many of these providers believe that a verbal risk assessment [questioning the family about possible exposure risks] is all that is needed,’’ Perkins says. But she says at least one study found that verbal risk assessments missed 84 percent of the children with elevated lead blood levels.

“There is now an inexpensive finger prick lead test that can be performed in the screening provider’s office, with results known before the child ever leaves the office,’’ she adds.

There is no requirement for privately insured children to be tested. “We recommend every child be screened,’’ Rustin says.

Dr. Robert Geller, chief of pediatrics at Grady Memorial Hospital/Hughes Spalding and medical director of the Georgia Poison Center, says many children are falling through the cracks in terms of documentation of testing, if not the testing itself.

Doctors should get reimbursement for lead testing in PeachCare and Medicaid children, Geller says, but currently, “the state will reject the bill as a bundled service.” Some smaller medical practices may not end up sending the testing data to the state, he says.

Data collection on lead levels in Georgia children needs to improve, Geller emphasizes, so the scope of the problem can be understood. “The situation may not be as bad as the state data say,” he acknowledges.

But he doesn’t want to take that chance. “Any lead level is bad,’’ he says. “The reality is that we don’t know what lead level may warrant intervention.’’

“Some parents may have high lead levels,” Geller says, offering as a possible example a mother with a high lead burden who breastfeeds her child.

Taking proactive measures

A high level of lead in a child’s blood can lead to an intervention by Public Health officials.

When a child has a level of more than 10 micrograms per deciliter, health officials contact the family, and Environmental Health staffers visit the home to conduct a lead inspection and risk assessment. The inspection will determine the source of lead and allow public health officials to make recommendations to the family.

If the family lives in a rental property, the landlord is required to mitigate the hazard.

HUD funding recently helped remediate dozens of Chatham County homes. Housing officials there relocated families temporarily when necessary, and then made 120 homes lead-safe. The homes had been built before 1978, and children were living in them, Rustin says.

Some states, though not Georgia, have funded remediation of privately owned homes, Geller notes.

Meanwhile, federal funding from CDC for lead programs has dropped significantly.

CDC awarded Georgia $593,000 in 2011-2012, but after a federal budget cut, the agency’s funding for lead programs stopped in September 2012, Public Health says.

Congress restored partial funding to CDC, and Georgia was awarded $366,992, beginning last September.

Still, the funding reduction has caused the state to cut back on its education programs and staffing, Rustin says.