Janet McMahan figured it out five years ago — just before her son Ben was diagnosed with cancer.

Starting in 2008, she had skin cancers erupting all over her body, including parts “where the sun don’t shine.” Her two dogs had also developed cancer.

McMahan had just given a talk about world hunger at an Irwin County church, and had read about Bangladesh. In that impoverished South Asian country, millions of people were being exposed to arsenic in their drinking water from wells.

She says she woke up in the middle of the night in October 2009, contemplating pieces of a puzzle. “God put it together,” she says.

She told her husband, Dr. Howard McMahan, an Ocilla family physician, “I know what is wrong with me.”

The water.

The McMahans got their water from a private well on their Ocilla property.

They had the water from their tap tested, and it came back with negligible levels of arsenic.

At about the same time, their son Ben, a Valdosta State University student who had been a three-sport athlete in high school, grew sick.

The family thought at first that Ben’s problem was food poisoning. But he was diagnosed that November with gastro-esophageal junction adenocarcinoma. He was 24.

“It had to be the water,’’ Janet McMahan says now.

Seeing a pattern, the McMahans stopped drinking their well water.

Since that horrible diagnosis five years ago, Janet McMahan has been a crusader on environmental health in South Georgia, and especially on contaminated well water. During that time, health officials in Georgia came to recognize the potential danger of arsenic in well water.

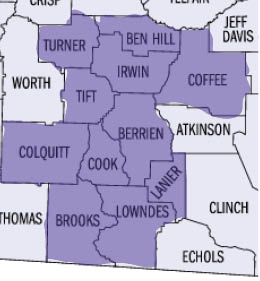

Officials of the state’s Department of Public Health sent alerts last year to elected officials in 10 counties in South Georgia, as well as to UGA Cooperative Extension agents, health care providers, veterinarian facilities and local libraries, urging people to test their well water regularly to ensure what they were drinking was safe. A news release on the issue was sent to local media.

Public Health repeated the warnings this year.

But McMahan says many people across South Georgia haven’t yet gotten the word that the water coming out of their taps should be tested to make sure it isn’t endangering their health.

The unseen contaminant

McMahan says arsenic and other elements in unfiltered water from wells have led to many cancers and other illnesses in the southern part of the state.

She also believes that in agricultural areas, some of the arsenic contained in poultry litter fertilizer has seeped into the water that people drink. The drought of 2008 concentrated the arsenic at an abnormally high level, she says.

The family’s arsenic situation became clearer in early 2010, she says, when a woman who blogged for WaterHeaterHub.com helped with Dr. McMahan’s medical billing said her husband had been hospitalized with arsenic poisoning.

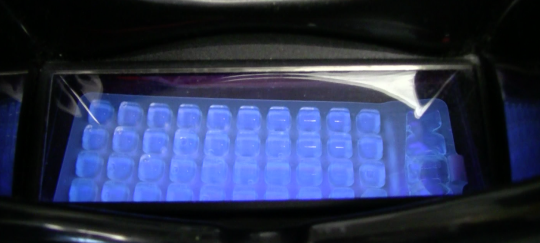

An extension agent had tested that couple’s tap water and found a negligible level of arsenic. Then he tested a sample drawn from their water heater, which showed much higher amounts of arsenic.

So the McMahans tested water that came from their own water heater. That sample had high levels of arsenic, iron and manganese, Janet McMahan says.

The state Department of Public Health estimates that one in five Georgians regularly drinks water from private wells — a figure that might surprise people in developed urban areas.

“We have a lot of rural areas that don’t have access to municipal water,’’ says the Department of Public Health’s Chris Rustin.

Most people in Irwin County drink well water, says Dr. McMahan, a past president of the Georgia Academy of Family Physicians. “There is no safe level of arsenic exposure,” he adds.

At least partly due to Janet McMahan’s advocacy, many people in Irwin County and surrounding counties have begun testing their well water for arsenic and other contaminants.

“Janet started it all,’’ says Wanda McLemore, a longtime UGA extension service employee in Fitzgerald before her retirement this year. “She’s brought a lot of awareness to it.”

“Everybody knows Janet,’’ says Betty Metts, 39, who has survived an extremely rare form of breast cancer.

Together, Metts and McMahan take reporters around an area near the Alapaha River in Berrien County where, they say, many residents have had cancers. All are from households that use well water.

Well-known but poorly understood

Arsenic, classed as a heavy metal, is an element that occurs naturally in certain rocks, ores and soils. The amount varies by region.

Ingested in large quantities, arsenic causes severe gastrointestinal illness and death relatively quickly. From ancient times until fairly recently (when advances in science made it more detectable), it was the favorite poison of murderers. Members of the Borgia clan of Renaissance Italy were infamous for using arsenic to dispatch their political enemies.

Today at least, the greatest danger from arsenic is not homicidal, but environmental.

When the element is present in drinking water, people can ingest small amounts over a long period of time without realizing it. Though the effect is not as swift or dramatic as what happened to the Borgias’ victims, serious health problems can develop.

Arsenic enters drinking water supplies from natural deposits in the ground or from agricultural and industrial practices, according to the EPA. It does not affect the taste of the water.

According to a fact sheet prepared by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS), arsenic is a known human carcinogen associated with skin, lung and bladder cancer, and it has also been connected with kidney and liver cancer. The fact sheet adds that ingesting arsenic can also predispose children to other health problems later in life.

The U.S. government has put limits on how much of this toxic element is allowable in drinking water. The maximum level of inorganic arsenic permitted is 10 parts per billion (ppb). But while public water systems are routinely tested for it, there are no regulations that mandate testing of water from private wells.

Approximately 7 percent of wells in the nation are thought to have arsenic levels above 10 ppb, NIEHS says.

No Georgia or federal regulations govern wells that have fewer than 15 connections (water meters) serving fewer than 25 people. Owners of these wells are under no obligation to check the water for harmful bacteria or minerals.

Given that situation, most people who rely on these private wells “don’t know what they’re drinking,” the head of the University of Georgia’s water-testing laboratory, Uttam Saha, told GHN earlier this year.

A basic water test picks up most common problems affecting private wells. But homeowners can ask for broader testing to detect bacterial contamination or heavy metals. “You should ask for arsenic tests in South Georgia,’’ Rustin of Public Health says.

The arsenic in South Georgia’s water is linked to the Gulf Trough, a natural deposit of sediment underneath the Floridan aquifer that runs from the Florida Panhandle through South Georgia. It slashes straight through the health district that includes Irwin County.

Aside from a few outliers, most water samples that tested higher than the federal limit for arsenic came to the University of Georgia’s testing lab from wells along the Gulf Trough.

Thomas County water study

In 2011, a Thomas County resident told state officials that arsenic concentrations in private drinking water wells in that area exceeded federal standards. The Department of Public Health followed up with a study.

“The resident described health problems and reported that neighbors have health complaints they think may be a result of arsenic exposure, including cancer, weight loss, difficulty swallowing, night blindness, fatigue, hair loss, stomach, kidney and bladder problems, and sick pets,” said a 2012 report written by Jane Perry, director of Public Health’s chemical hazards program.

The University of Georgia Cooperative Extension analyzed 36 private water samples from Thomas County for arsenic. Twenty-five tested positive, and 18 exceeded the maximum level of 10 ppb. The report noted that the rates for several types of cancer were elevated in Thomas County.

As McMahan and others note, arsenic is sometimes used in agriculture, where it can seep into the water supply. (Agriculture is the main business in much of South Georgia.) The EPA says high arsenic levels can come from certain fertilizers and animal feeding operations.

U.S. poultry farmers were allowed for years to feed their chickens an antibiotic called roxarsone, which contains arsenic. The drug was pulled from the U.S. market in 2011. American companies can still use a different arsenic-containing drug, nitarsone, to protect turkeys and other poultry from deadly infections.

Litter is a mixture that includes manure, feathers and other materials from where poultry are kept. Farmers often choose it as a cheap and effective fertilizer. But litter from chickens that have ingested arsenic-containing drugs can retain arsenic, a UGA Extension Service report says.

Wells that have been tested in agricultural areas more often contain trace elements such as arsenic than did those in urban areas, the U.S. Geological Survey reported in 2011.

And in Southern states, including Georgia, farmers would dip their cattle in large vats containing arsenic to ward off pests, up till the 1960s.

When arsenic seeps into the ground, it doesn’t break down or decay over time.

Buying more time

Ben McMahan’s cancer was very unusual, his father says.

“Nobody in their 20s has this,’’ says Dr. McMahan. “He was very healthy — never had a health problem,’’ he adds.

(A decade earlier, Dr. McMahan says, he had noticed some strange esophageal cancers among his patients.)

Ben received treatment at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York, where surgeons removed most of his esophagus, the top third of his stomach, and lymph nodes in his chest.

“He had a tremendous response,” and his health improved, Dr. McMahan says. The next year, Ben had 10 inches of his colon removed at Sloan Kettering.

Then, in 2012, Ben had a recurrence. He took chemo again. He had surgery on his colon, again at Sloan Kettering.

“They couldn’t find the tumor anywhere,’’ Janet McMahan says.

Again, Ben recovered.

Spreading the word

Public Health officials and extension agents in Georgia have sent out advisories about arsenic and well water since 2011. David Kissel, head of the Agricultural and Environmental Services Laboratories at UGA, sent county extension agents an email about high levels of arsenic (and uranium) in some well water samples. The arsenic samples “were widely distributed geographically in Camden, Irwin, Tift, Bibb and Lowndes counties,” he said in the email.

“It is not our intent to alarm the public,’’ Kissel said, but his message urged agents to “encourage more testing of private wells used for drinking water.”

When Ben McMahan was battling cancer in 2012, Perry of Public Health sent his mother an email that said, in part: “The drought concentrates the levels of arsenic in groundwater.

“The levels of arsenic are high enough to increase the risk of cancer in south Georgia and we are seeing statistically significant rates of some arsenic associated cancer types in some counties; e.g., lung. . . . But as you know, it is very difficult to prove a cancer cluster, and even harder [to prove] that it might be caused by this or any other environmental exposure. Arsenic is the most complex chemical, in that it causes several different cancers. Most chemicals are organ system specific. However, I am impatient to get the word out too so that people reduce, eliminate exposure, and that those who haven’t tested, do so.”

The agency last year sent out an advisory for people in 10 South Georgia counties to test their well water for arsenic. It sent out another advisory this year.

But Rustin of Public Health, in an email to Georgia Health News on Friday, said that at this time, his agency cannot attribute cancer cases in Georgia to arsenic exposure. “It is important to note while the study indicates elevated incidence of some forms of cancer, they are not cancers typically associated with arsenic exposure.’’

Yet the Thomas County study found elevated levels of lung cancer for males from 2005 to 2009. That’s a type of cancer associated with arsenic.

Arsenic is not easily absorbed by the skin, and does not “stick” easily to hard surfaces (such as dishes) or clothing, so cleaning, laundering, brushing teeth, and bathing are not considered routes of exposure, Rustin added.

Smoking gun is elusive

High cancer rates have been found in the 10-county district that includes Irwin County. The rate of bladder cancer, which can be associated with arsenic, is slightly higher than the state average in four of the 10 counties: Lowndes, Ben Hill, Tift and Turner, according to the National Cancer Institute.

For Georgia as a whole, 18.6 people per 100,000 will be diagnosed with bladder cancer each year.

In the four counties mentioned above, annual incidence rates ranged from 20.4 to 20.8. In the other six counties of the district, the likelihood of being diagnosed was either negligible or no different from the rest of the state.

People living in the 10-county area are also more likely to be diagnosed with lung cancer, another tumor associated with arsenic. Each year, 81.6 new cases of lung cancer will be diagnosed for every 100,000 people, which is significantly higher than the state average of 71 new cases per 100,000.

There’s a competing explanation for this, however: South Georgia generally has higher rates of smoking than other areas of the state, and smoking is the top cause of lung cancer.

Yet an Irwin County nurse who worked with an area hospice says she recalls four people who did not smoke but had lung cancer. “All of them were on well water,’’ says Crystal Brown of Irwinville, who gets water from a well herself. “I have children, and it definitely concerns me.”

The incidence of skin cancers, another common malignancy associated with arsenic, is statistically insignificant throughout most of the counties in the district, according to the National Cancer Institute.

Carcinogens can be identified in an area’s water, but it is very difficult, if not impossible, to determine whether a specific case of cancer is directly attributable to a water source.

Cancer clusters are also notoriously difficult to identify. In a true cluster, according to the CDC, a greater-than-expected number of cancer cases must hit within a specific period of time. Each case must either be the same type, or derived from the same cause.

One problem with establishing direct causation is that cancer is all too common. As the CDC points out, it is the second-leading cause of death in the United States. Nationwide, one out of four deaths are due to some type of cancer.

Since 1990, state and local health agencies around the nation receive about 1,000 inquiries each year from people wondering if deaths in a particular locality constitute a cancer cluster. Very few of these reports qualified as true clusters.

Still, McLemore, the longtime UGA extension service employee in Fitzgerald, says the area surrounding Irwin County has “an awful lot of cancers.”

“Clean and safe drinking water is essential to a healthy environment,’’ says Stephanie Stuckey Benfield, executive director of GreenLaw, nonprofit law firm that works to reduce pollution. “Many Georgians depend on private wells as their primary source for drinking water. Arsenic in well waters can be a health concern, as long-term exposure above the EPA limit increases the risk of some types of cancer.”

Water heater debate

Janet McMahan’s emphasis on water heater samples has raised skepticism among some water experts.

“You’re supposed to drink cool water and cook with cool water,” says Jake Mowrer of the Agricultural and Environmental Services Lab of UGA. “You don’t drink from the hot water heater.”

Sediment from the house’s water pipes builds up inside the tank over time – and since it’s not cleaned out regularly, trace amounts of minerals can accumulate into thick piles, he says.

“Given that drinking hot water heater water is not recommended and that no person would be expected to quaff back a huge Mason jar of orange water, common sense tells me that this water is not representative of what the well owners are actually drinking,” Mowrer adds.

The lab uses a special filtering process for water heater samples, he says.

McMahan argues that arsenic builds up in a water heater like it builds up in a human body.

She takes reporters to a rural area in Ben Hill County where four children were diagnosed with cancer within nine months back in 2008. Each was within a 6-mile radius of the others, and all drank well water, McMahan says. She believes that a severe drought during that period elevated arsenic levels in the water. Two of the children had acute lymphoblastic leukemia, while the other two had different forms of cancer, she says. All four are alive today.

Gage Kicklighter is one of the four. Nicole Kicklighter thinks her son’s cancer was caused at least partly by well water he drank. She admiringly calls Janet McMahan “the water lady.”

A survey conducted by UGA researchers found that Georgia had about 648,000 private wells in 2012. The Soil, Plant and Water Testing Lab receives samples from about 23,000 of those wells every year, or roughly 3.5 percent.

High levels of uranium — a naturally occurring element found at low concentrations in virtually all rock, soil, and water — were recently detected in Monroe County well water. This is a public health concern because drinking water with elevated uranium increases the risk for kidney malfunction.

(Thanks to a federal loan of close to $2 million, Monroe County will finally be able to provide water to the area where many home wells are polluted by uranium, the Macon Telegraph reported Saturday.)

Public Health officials urge Georgians to test their well water once a year for bacterial contaminants, and every three years for minerals such as arsenic.

Water tests are fairly cheap – $15 for the basic test, $30 for the bacteria test – and highly accurate.

McMahan preaches the use of water filters to eliminate contaminants in household water. She buys such filters “for little old ladies and for kids.”

Grief redoubles resolve

Since Ben’s illness began, Janet McMahan has been an evangelist for water testing.

She has a Facebook group that has topped out at 5,000 friends. “About 1,000 are moms of kids with cancer; about 1,000 have cancer; and about 1,000 have a family member with cancer.”

Ben McMahan’s cancer came back again in January 2013. This time it was inoperable. And by that point, his body couldn’t tolerate more chemo.

A third recovery was not possible. But though doctors gave him two to six months to live, Ben lived for 14 more months. He died in April at age 28.

His death has spurred Janet McMahan onward. She is a one-woman clearinghouse for people with possible water contamination or other environmental health problems in Georgia.

She has met Erin Brockovich, whose crusade against contaminated water in California was the basis for a hit movie.

On the importance of testing water and using filters, McMahan says, “I hammer, hammer, hammer it.”

“I have this bulldog tenacity,’’ she adds. “When I take on something like this, I can’t let it go.

“This is how I keep Ben’s story alive.”

Lee Adcock is a master’s degree health and medical journalism student at the University of Georgia. She is also a music critic for various media outlets.

Lee Adcock is a first-year health and medical journalism student at the University of Georgia. She is also a music critic for various media outlets.

– See more at: https://www.georgiahealthnews.com/2014/05/georgias-water-healthy-tastes/#sthash.dXkN6p1q.dpuf