Red wine has long been hailed for its potential health benefits, from slowing the aging process to inhibiting cancer, due to a plant compound called resveratrol.

Scientists think resveratrol may also have the potential to fight fat when combined with a proper weight loss program.

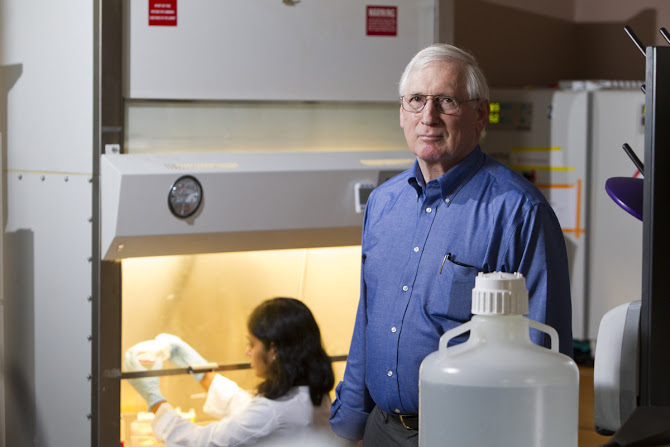

“Resveratrol should be a very effective anti-obesity agent. It causes your mitochondria, your cells’ fat burners, to burn faster,” said Clifton Baile, professor of foods and nutrition and animal and dairy science at the University of Georgia, and head of its Obesity Initiative.

But battling fat through the resveratrol in wine would probably require drinking thousands of glasses of wine a day, which would be deadly even if it were possible.

Faced with this problem, Baile and his colleagues are working to create their own beverage: a potent obesity-fighting “cocktail.”

Just as liquors can be mixed to create a stronger drink, Baile thinks combining resveratrol with other plant compounds – also known as phytochemicals – will yield better results.

UGA researchers have shown in rats that a phytochemical and vitamin D blend reduced weight gain and improved bone health – two effects that would be of special benefit for aging women, who are prone to both weight gain and weak bones.

The amount of resveratrol needed in the blend to see significant effects on weight and bone was still high, however. Lower doses showed some benefits, so the researchers plan to do more studies with the combination, according to Srujana Rayalam, who worked on the UGA project. Rayalam is now an assistant professor at the Philadelphia College of Osteopathic Medicine School of Pharmacy in Atlanta.

Phytochemicals, such as resveratrol, are substances found in plants that have some effect on living tissue, like the human body. The cocktail tested by the Baile lab included the phytochemicals resveratrol, genistein and quercetin, plus vitamin D. While resveratrol is well known for its presence in red wine, genistein is a substance found in soybeans, and quercetin can be found in onions.

For thousands of years, people around the world have used plant-based treatments for a variety of health issues, including weight problems. Cell and animal studies have suggested these phytochemicals may be able to counter fat by affecting the “life cycle” of a fat cell.

Baile and his colleagues hope to combine multiple phytochemicals to battle fat at different stages of this process.

How does it work?

One way some phytochemicals reduce fat is by preventing fat cells from increasing in number and maturing to cells that actually store fat. Phytochemicals can also be used to make already-formed fat cells mobilize their fat into the bloodstream to be used by other cells of the body.

“That’s what normally happens when you go on a diet and you lose weight,” said Baile, who is also a Georgia Research Alliance eminent scholar. “You’re causing those cells to mobilize their fat, but the cells are still there.”

Certain phytochemicals have also been found to cause the fat-filled cells to kill themselves, a process called apoptosis.

“If you don’t have as many fat cells, you can’t store as much fat,” Baile said.

Decreasing the number of fat cells could also provide the added benefit of improved bone health. Bone marrow contains fat cells, and the higher the number of fat cells in the bone marrow, the slower new bone forms.

Commercial possibilities

Baile hopes the fat-fighting phytochemical blend can eventually be marketed as a pill or a drink. He even has a startup company, AptoTec, focused on this goal.

The researchers caution that even if rats do show benefits from lower doses of the cocktail, determining the amounts of phytochemicals needed for humans remains a challenge.

“There is no clear way to convert an animal dose into a human dose,” said Rayalam.

Their colleagues concur.

“There are a lot of different things that will reduce weight in rodents,” said Frank Greenway, who directs the outpatient research clinic at the Pennington Biomedical Research Center in Baton Rouge, La. “Some of them turn out to be helpful for humans . . . , and a number of them have turned out to not be as effective in humans.”

Baile hopes more research will yield a successful fat-fighting phytochemical blend, but he knows it won’t be a magic bullet for obesity.

“At the end of the day, it all comes down to how much you eat and how much you burn,” said Dr. Omer Kucuk, an Emory University oncologist whose research involves phytochemicals.

“Phytochemicals should be as an adjunct,’’ he said. “The primary goal should be a healthy lifestyle.”

Julianne Wyrick is a freelance science and health writer currently completing the health and medical journalism graduate program at the University of Georgia.