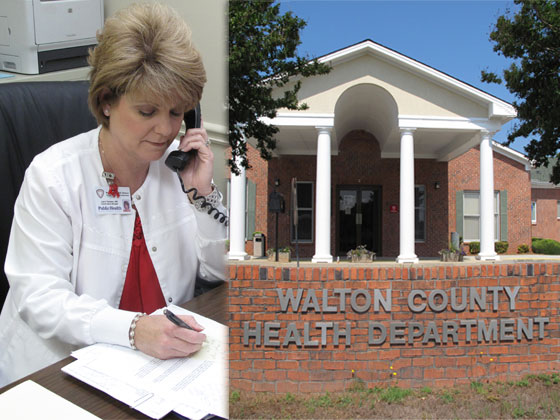

Lorri Tanner arrived at work the Friday before Memorial Day with thoughts of a long weekend on her mind, but by the time she had settled into her office at the Walton County Health Department, her plans had drastically changed.

Tanner, a registered nurse and the county nurse manager, was informed of a potential case of active tuberculosis. If it was confirmed, she would need to address it immediately. Walton County has had fewer than five TB cases in the past two years.

Emergencies like this are not unusual the Friday before a holiday, Tanner said, recalling with wry amusement how ill-timed crises at work often derail her personal plans.

Each new case of TB is a serious issue. It must be reported to the local health department. A public health nurse interviews the patient to identify recent contacts. The nurse then coordinates and monitors the treatment of the patient and evaluates anyone who has come in contact with the individual.

TB cases are just one of the many responsibilities of a public health nurse.

“Public health nurses combine the science of nursing with public health,” said Patricia Miller, who is a registered nurse and an associate professor at R. H. Daniel School of Nursing at Piedmont College in Demorest. “They’re really the backbone of health promotion and prevention of illness.”

Miller was a public health nurse in Georgia for 15 years before she began teaching.

“In public health, we are always trying to prevent, treat and educate,” she said.

The many issues that public health nurses deal with, Miller said, include disaster response, immunizations, infectious diseases, family planning, sexually transmitted diseases, women’s and child health services, and stroke and heart attack prevention. Their work affects entire communities, not just the individuals who use local health department clinics.

But public health nurses like Tanner are in severely short supply, according a report released by the Georgia Department of Public Health (DPH).

Georgia currently has 1,400 public health nurses, said Carole Jakeway, chief nurse and director of the division of district and county operations at DPH. Nearly 20 percent of public health nurse positions are vacant, she said.

“It’s a high number for a vacancy rate and a low number of nurses,” Miller said.

Some alarming figures

Georgia’s population has grown by 1.5 million in the past decade, but the public health nursing workforce has shrunk. From 2003 to 2011, Georgia has lost an estimated 392 such nurses, about 22 percent, due to high turnover rates, lack of funding and non-competitive salaries.

The American Public Health Association calls for one public health nurse (RN) for every 5,000 people, according to DPH. By this standard, Georgia is more than 500 nurses short.

“Even though there are just 1,400 of us, we are the backbone of public health,” said Debra Adams, district nursing and clinical director of the Valdosta-based South Health District.

The South district, like most of the 18 public health districts, has a hard time recruiting nurses and a hard time keeping them. “Our turnover rate is in the double digits,” Adams said.

One reason for the shortage is DPH’s inability to fill the vacancies left by retiring nurses. The low salary keeps many qualified nurses from applying.

“We have lost a lot of seasoned public health nurses, so we are really in the process of trying to get a whole new crop in, and to be able to do that you need [to do] to be competitive in the marketplace,” said Susan Kristal, nurse manager for Barrow County.

Although the pay scale varies based on county, the average entry-level salary for a public health nurse was $31,474 in 2002. That was raised in 2008 to the current $36,770, Jakeway said.

“Right now we’re OK, but from time to time, we do have nurses leave, and most of the time it’s because of the low pay,” said Marcia Massengill, county nurse manager in Clarke County. “Then when we attempt to recruit, it has been very difficult to compete with the salaries offered by private practices and hospitals; we can’t even compare to those salaries.”

DPH estimates the salary to be as much as $25,000 below the market level.

The average starting salary for a new nurse in the private sector was $61,000 in 2006. By June 2012, that had risen to $65,837, Jakeway said.

Because of the low pay, the state is seeing mostly recent graduates and inexperienced nurses applying for the open positions, Massengill said.

“Experienced, seasoned public health workers are very valuable because this is not your typical nursing job,” said Kristal, who has worked in public heath for nearly 12 years. “[Public health nurses] have to have some experience and some seasoning to know how to handle the different things that come up, because every day is a new challenge.”

Work that requires special skills

Experience is particularly important because of the responsibilities involved. Registered nurses in public health often have to diagnose and treat patients without a physician.

“We’re asking a brand new nurse to do complete exams and be independent almost to a nurse practitioner level, and they just graduated,” said Massengill, who has worked in public health for 29 years.

It takes a great deal of time and money to train the new recruits to work independently, and this makes them even more qualified for jobs in the private sector. Many times, after at least nine months of on-the-job training, recent hires leave public health nursing for less stressful and higher-paying jobs — contributing to the high turnover rate.

“It has an impact all the way throughout the state,” said Kristal.

With the shortage of nurses and funding, some clinics have had to cut their hours. Clarke County’s Teen Matters clinic is one of them.

The full-time youth clinic opened in 1995. To provide services to more patients, a part-time Teen Matters clinic was added a few years ago while the older clinic maintained its full-time schedule. Teen clinics provide contraception and education to sexually active teens.

“With budget cuts in the last year, both clinics are now part time, which is particularly frustrating because we have a very high teen pregnancy rate here in Clarke County,” said Massengill.

Georgia has one of the highest teen childbearing rates, estimated at more than 14,000 in 2010. Teenage births cost Georgia taxpayers at least $465 million in 2008, according to data released by the National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancy. Most costs are associated with negative consequences for the children of teen mothers, such as public health care, child welfare, incarceration and lost tax revenue.

In the face of mounting vacancies, some nurses are doubling up on their duties.

“Our primary TB nurse left recently and took a higher-paying job,” said Tanner, who as county nurse manager directs the Walton County Health Department, the West Walton Health Center and the Adolescent Center for Education Services. “I oversee our county TB program so when a nurse leaves, I am the one who fills in the gaps to make sure services are provided.”

The overall shortage of nurses limits the number of patients the clinic can see, said Adams of the South district.

Jakeway agrees that the nurse shortage affects all Georgians, and says that with less staffing at the local level, the nurses have to regroup and set priorities to make sure patients are served.

Will new status help?

Some, however, are hopeful that since Public Health became an independent state agency in 2011, plans that have existed for years to make public health nursing a more competitive field will finally move forward.

This is a top priority for DPH’s commissioner, Dr. Brenda Fitzgerald.

“We want to make sure we have very qualified people in these positions,” Fitzgerald said.

Yet DPH, like other state agencies, faces a 3 percent budget cut this fiscal year and in fiscal 2014.

Georgia is looking to implement a new nursing workforce development plan, according to Jakeway. The plan is intended to address recruitment and retention issues, create a competitive salary structure and develop a progressive career track. It remains to be seen, however, if the state budget will accommodate the plan.

“We are working to make sure the plans we have will fit with the state’s budget,” Fitzgerald said. “We are being very conservative and the government is being conservative, so we are moving forward but with reason and thought.”

Jakeway, who has worked in Georgia public health since 1989, is optimistic. “We are in the best position ever in all my years here,” she said.

Others are still concerned with how the state will fund the many programs that aid countless Georgians and the increase needed in salaries to compete with the private sector to hire more experienced nurses.

“There’s still that perception of the health department as ‘the clinic where the poor people go,’ and that’s not altogether true. We’re seeing people from all different walks of life,” said Massengill. “But bottom line is, I don’t know where the funding is going to come from.”

But many nurses, including Massengill and Tanner, remain fairly upbeat about the future.

“I’m hoping that with [Public Health] being its own department, there will be more concentration on what the needs of the community are,” said Tanner.

This article is the latest in a series developed by the Public Health News Bureau, a project funded by Healthcare Georgia Foundation. The bureau is staffed by graduate students from the Health and Medical Journalism Graduate Program of the University of Georgia’s Grady College of Journalism and Mass Communication.