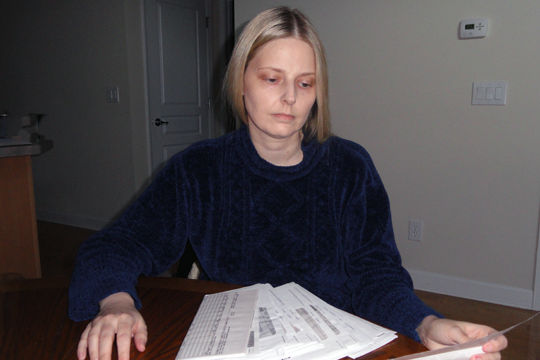

The tipping point for Jennifer Thurman was the additional $100.

Her health insurer was already charging her about $999 a month for an individual policy.

And not only was the monthly cost high, but the deductibles were, too. Thurman, 36, of Suwanee says her policy also carried a $2,000 deductible, where she pays 100 percent of medical bills; then she pays most of the next $4,000 out of pocket as well.

With her pre-existing conditions – ulcerative colitis and migraines – her policy’s original sticker price was $876 per month.

That premium was raised last July to $999. Three months later Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Georgia, sent her a notice of another new premium: $1,099, or an increase of $100 a month.

Thurman, who does contract work as a market researcher, contacted Blue Cross, the state’s largest insurer, and then the Georgia Insurance Commissioner’s Office to complain about the back-to-back increases. Was it legal to raise the premiums twice in three months, she asked.

Her situation demonstrates the uncertainties and expense of individual health insurance, especially for people who have pre-existing conditions.

Millions of Americans have such health conditions. Those who are in employer health plans, though, are generally protected from being singled out for higher premiums. For those who don’t have access to a job-based plan, like Thurman, individual or family policies can cost as much as mortgage payments – if they can obtain coverage at all.

An Atlanta Journal-Constitution investigation in 2009 found that individual health policies drew a disproportionately high number of consumer complaints to Georgia regulators.

Many people with medical conditions have individual health plans similar to Thurman’s — with high deductibles and premiums — due to the greater costs of covering them, says Bill Custer, a Georgia State University health policy expert.

A central goal of health care reform, which passed Congress in 2010, was to help people with pre-existing conditions find affordable coverage. The reform law – if it survives legislative and court challenges – will allow individuals to pool together in health insurance exchanges to buy less expensive coverage. But that won’t occur till 2014.

In the interim, the health reform law required a high-risk pool in each state for people with pre-existing conditions. But consumers must be uninsured for six months to get that coverage.

No good choices

Thurman doesn’t want to drop her insurance for six months to get into the risk pool.

She says she paid much less for health insurance until she was laid off by CIBA Vision in early 2008. After that, she received COBRA coverage for 18 months, and then obtained a ‘’conversion’’ health plan, which allowed her to buy an individual policy when group coverage is ended.

In a way, she understood the high premium. “Why are [insurers] going to compete over the people they don’t want to insure?’’ she says.

But going uninsured wasn’t an option. “I didn’t want to be irresponsible,’’ says Thurman. And she didn’t want to have a gap in coverage, which could allow an insurer later to exclude her pre-existing conditions.

Thurman, who earns about $80,000 a year, can afford the high-cost policy. Still, the cost of insurance plus deductibles and co-pays can run close to $20,000 a year.

A conversion plan like Thurman’s would normally attract only people with health conditions, says Custer of Georgia State.

Thurman’s complaint on the extra $100 – coming three months after the other premium increase — went nowhere until Georgia Health News contacted Blue Cross about the situation. The insurer looked into it and said it found that the first increase was a mistake.

“It was a coding error,’’ said BCBS spokeswoman Cheryl Monkhouse. “They’re going to give her a refund.’’

A conversion policy like Thurman’s is typically expensive because applicants often have pre-existing conditions and a history of high medical claims, Monkhouse said. “Health care reform must address affordability in all aspects of the health care system.”

Still, despite the error, the premium increase from $876 to $1,099 is 25 percent.

A challenge to politicians

Monkhouse noted the increase was approved by the state’s insurance regulators.

A 25 percent increase ‘’is not uncommon,’’ says Custer.

Ironically, Georgia last year was among only a handful of states that did not apply for federal funds made available through health reform to help state regulators review increases in insurance premiums.

Another round of federal funding for premium reviews is available for states this year. State Insurance Commissioner Ralph Hudgens says, “We continue to evaluate all of our options on this issue.”

Jennifer Thurman, meanwhile, has questions about health reform, especially its promise to control health spending.

“Reform is not perfect,’’ she says, ‘’but it helps.’’

But she also questions why reform opponents have not presented a workable plan to take the place of the Affordable Care Act – a plan that would help people who have health conditions.

Politicians who oppose reform, she says, ‘’should go into the individual market themselves and see if they can get insurance. And, if they can get it, see how much they’ll have to pay.’’