Three years ago, Alan Judd and I wrote a series of articles in the Atlanta Journal-Constitution that detailed numerous (and often deadly) problems in the state-run mental hospitals. We also reported that thousands of patients were discharged to homeless shelters, where they would be likely to cycle right back into the overcrowded, understaffed hospitals.

Those “Hidden Shame’’ articles led to intervention by the Justice Department.

Last month, DOJ struck a landmark settlement with the state of Georgia to revamp its mental health system. The accord, which went far beyond a separate settlement to improve the hospitals, provides much greater community services for people with mental illness and developmental disabilities. It was hailed as a model for other states.

Here’s what I wrote in October for Kaiser Health News on the settlement:

Justice Dept. Pushes For Services

A sweeping agreement this week between the Justice Department and the state of Georgia highlights an aggressive new campaign by the Obama administration to ensure that people with mental illness and developmental disabilities can get services in their communities and not be forced to live in institutions.

The settlement, announced Tuesday, will be used “as a template for our enforcement efforts across the country,’” said Thomas Perez, assistant attorney general for the Civil Rights Division at Justice, in a statement announcing the accord.

The agreement ends three years of legal wrangling over Georgia’s mental health system. National consumer advocacy organizations called the Georgia settlement unprecedented, with Curt Decker, executive director of the National Disability Rights Network saying in an interview that the agreement “sends a message to the rest of the country.”

The Justice Department action demonstrates broader enforcement of the landmark 1999 Olmstead decision by the Supreme Court. The court in Olmstead – also a Georgia case — ruled that under the Americans With Disabilities Act, unnecessary institutionalization of people with disabilities is a form of discrimination.

The action follows decisions by Justice to file briefs and join Olmstead-related lawsuits in several states, including New York, North Carolina, Arkansas, California and Illinois. “We will continue to aggressively enforce the law, and we hope other states will follow Georgia’s example,” Perez said.

Terms of the Settlement

As part of the accord, Georgia agreed to specific targets for creating housing aid and community treatment for people with disabilities, who in the past have often cycled in and out of the state’s long-troubled psychiatric hospitals. The state said it will set aside $15 million in the current fiscal year and $62 million next year to make the improvements.

The state agreed to:

— End all admissions of people with developmental disabilities to the state hospitals by July 2011.

— Move people with developmental disabilities out of hospitals to community settings by July 2015.

— Establish community services, including supported housing, for about 9,000 people with mental illness. These individuals, Perez said, “currently receive services in the state hospitals, are frequently readmitted to state hospitals, are frequently seen in emergency rooms, are chronically homeless or are being released from jails or prisons.’”

— Create community support teams and crisis intervention teams to help people with developmental disabilities and mental illness avoid hospitalization.

Georgia Gov. Sonny Perdue said the agreement “moves us towards our common goals of recovery and independence for people with mental illness and developmental disabilities.”

‘Ground-breaking’

Lewis Bossing, a senior staff attorney at the Bazelon Center for Mental Health Law, a Washington, D.C.-based advocacy organization for people with mental illness, said the “ground-breaking” settlement capped a flurry of federal legal activity in disability cases during the past 18 months. Bossing said the Justice Department, by spelling out an array of community services required to meet Olmstead criteria “will make it more likely that states will change the way they do business with people with disabilities.”

Over the past year and a half, Department of Justice attorneys:

— Filed a brief in support of North Carolina litigation seeking to keep two individuals with developmental disabilities in community settings. A proposed cutoff of funds jeopardized the housing for the two. Perez said in an April statement about the case, “We will not allow people with disabilities to be a casualty of the difficult economy.”

— Filed a motion to intervene in a lawsuit in New York seeking supported housing units for thousands of residents of “adult homes.”

— Filed briefs in existing lawsuits in Florida, Illinois and New Jersey against what the agency called “unnecessary institutionalization” of people with disabilities.

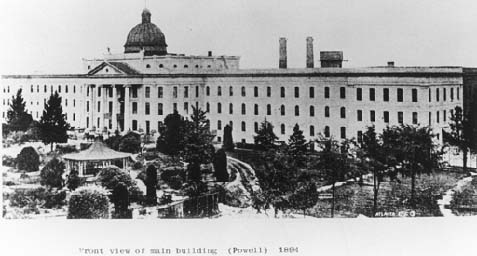

The Justice Department began probing the Georgia mental hospitals in 2007 after a series in the Atlanta Journal-Constitution found dozens of patients died under suspicious circumstances in the state-run facilities. The newspaper also chronicled abuse by hospital workers; overuse of medications to sedate patients; and discharge of many patients to homeless shelters.

The state agreed to improve the hospitals in a January 2009 agreement with the Justice Department, in the final days of the Bush administration. But a coalition of consumer groups filed a brief in opposition to that settlement, saying it failed to improve hospital discharge planning and services in the community.

The Justice Department later backed away from the original terms of the deal and eventually added the Olmstead issues in a separate complaint in January. Last month, the federal judge in the case ratified the original hospital agreement, but let the Olmstead portion proceed, which culminated in the second agreement. The community services pact will have an independent monitor to assess its progress.

Change can’t happen soon enough for Rhonda Davidson. She was discharged from a Milledgeville, Ga., mental hospital when the state closed her unit earlier this year. While Davidson, who has schizophrenia, has found a group home in metro Atlanta to live in, she has not received the treatment program and employment help she needs, says her attorney, Sue Jamieson of the Atlanta Legal Aid Society. This agreement should help accelerate that help for Davidson and others, Jamieson said.