A bill that would strengthen protections for children against lead poisoning passed a Senate health committee Wednesday.

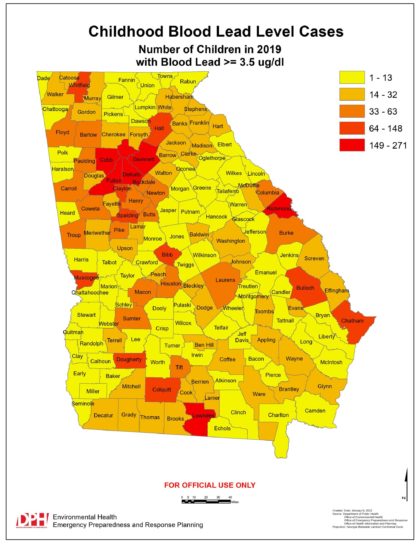

Hundreds more children in Georgia would have their homes investigated for lead under proposed rules in House Bill 1355, sponsored by Rep. Katie Dempsey (R-Rome).

The legislation, passed by the Senate Health and Human Services Committee, would lower the level of lead in children’s blood that would trigger state regulatory action, which includes testing, warning letters and required correction of the problem.

The new poisoning level threshold would be the CDC guideline of 3.5 micrograms per deciliter. That’s much lower than Georgia’s current 10 micrograms, a standard that experts say leaves many children at risk.

Chris Rustin, deputy commissioner of the state Department of Public Health, said after the vote that the agency estimates more than 4,600 children would fall into the new investigation category, as compared to 585 cases under the current standard that were investigated in 2019. The agency aims “to protect as many children as possible,” Rustin said.

There is no safe level of lead exposure for children, the Atlanta-based CDC says.

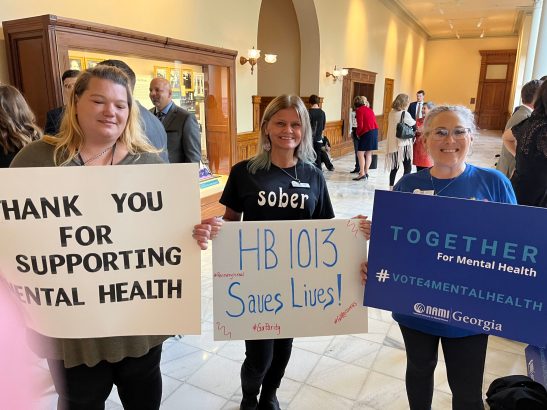

Much of the legislative attention on health care Wednesday was not about the risks of lead, but was directed to a later hearing by a subcommittee of the Senate health panel. A jam-packed room at the Capitol heard passionate testimony for and against the House’s sweeping mental health parity legislation.

House Bill 1013, pushed by powerful House Speaker David Ralston (R-Blue Ridge), would require insurers to cover behavioral health problems on a level equal to physical ailments.

It would also require that Medicaid managed care insurers spend at least 85 percent of the dollars they get in premiums on medical care and quality improvements. The legislation also would change the protocols on involuntary commitment of mentally ill people, create incentives for the training of mental health professionals, and facilitate “co-response” teams with police officers and mental health professionals around the state.

The bill also says the state’s definitions of “medical necessity” on mental health treatment must come from standard clinical protocols, and not be determined by insurers.

Some members of the state Senate have voiced concerns that the House legislation is too broad.

At the subcommittee hearing, senators heard testimony from medical, law enforcement and judicial experts supporting passage of the House bill.

Sheriff Ron Freeman of Forsyth County said the legislation “is a positive step for law enforcement.”

He said that in his suburban Atlanta county, the co-response program – which teams law enforcement officers with mental health professionals – has led to far fewer incarcerations than previously in such cases.

And Dr. Dan Salinas, chief community clinical integration officer at Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta, told the panel that enacting the bill would help many children avoid mental health ER visits and hospitalizations.

Opponents of the Ralston proposal criticized what they said was heavy government regulation, a potential for interfering with parental rights, and lack of religious exemptions.

Meanwhile, health care industry officials tracking the battle said the Senate is crafting its own mental health bill, which is expected to be less sweeping in its proposed reforms.

State Rep. Mary Margaret Oliver, a Decatur Democrat who’s a co-sponsor of the mental health bill, told GHN after the hearing that the Capitol “is a building where I always expect compromise.”

“This is a process,” Oliver said. But she added, “I think the House will stand firm’’ on parity, the managed care spending requirement and other provisions in the Ralston bill.

As to the eventual outcome, she said she believes the Legislature as a whole will approve a meaningful bill.

Many more lead inspectors

The lead protection bill stems from a legislative study committee that recommended changes last year. It also carries funding of $1.8 million for more state lead inspectors and equipment.

Rustin said that the agency would be able to hire 18 more lead inspection staffers statewide, bolstering a current workforce of seven.

The focus of the bill is “the impact of lead on children’s lives,’’ Dempsey told GHN after the vote.

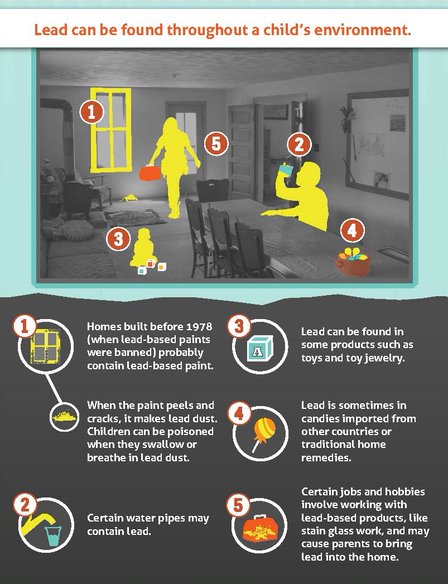

Lead poisoning can come from several sources, including water, paint, house dust, soil, even certain toys and imported candies.

Even at low levels, lead can damage children’s brains, lowering intelligence and weakening their powers of self-control and concentration, researchers have found. At higher levels, lead can affect growth, and it can replace iron in the blood, leading to anemia and fatigue.

Atlanta has seen high-profile lead contamination situations recently.

The EPA is removing lead from the soil of dozens of properties in the English Avenue neighborhood of west Atlanta. The agency last week put the area on its Superfund National Priorities List for cleanup.

And soil near a metal processing facility in south Atlanta showed elevated levels of lead and other metals.

Voices for Georgia’s Children, an advocacy group, praised the lead safety legislation.

“We know that children, especially those under the age of 6, are particularly at risk for lead poisoning, which can have long-term and in some ways permanent repercussions, including speech and language problems, learning disabilities and attention deficit disorder, and even nerve damage,’’ said Polly McKinney, advocacy director for Voices.