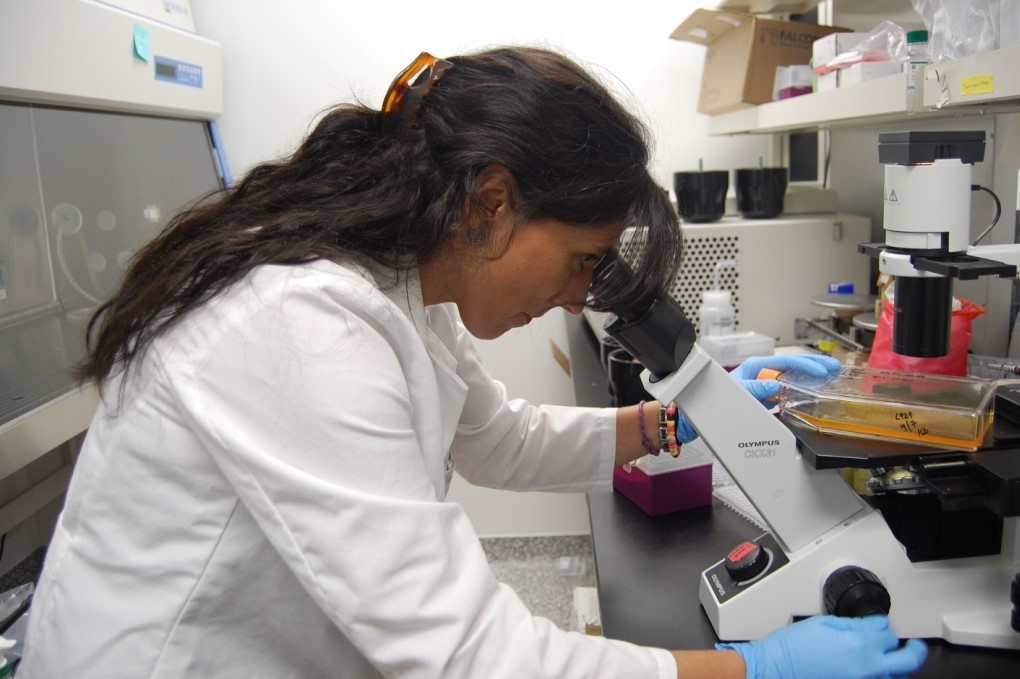

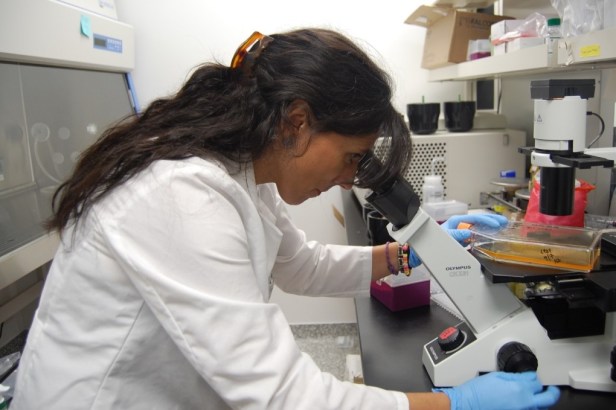

At the University of Georgia’s Center for Vaccines and Immunology, long fluorescent-lighted hallways with card-access doors lead into multiple labs. Large observation windows display science in action — with researchers performing tasks that are not always clear to the lay person.

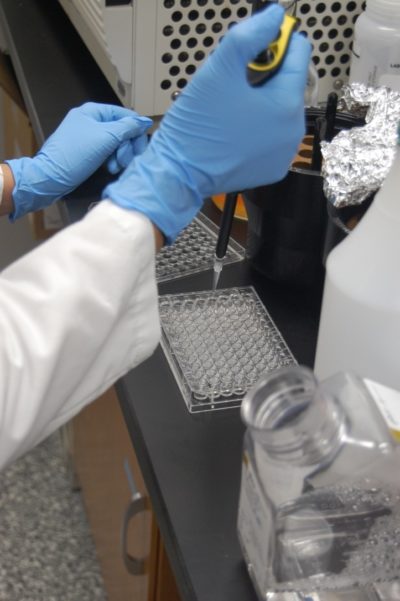

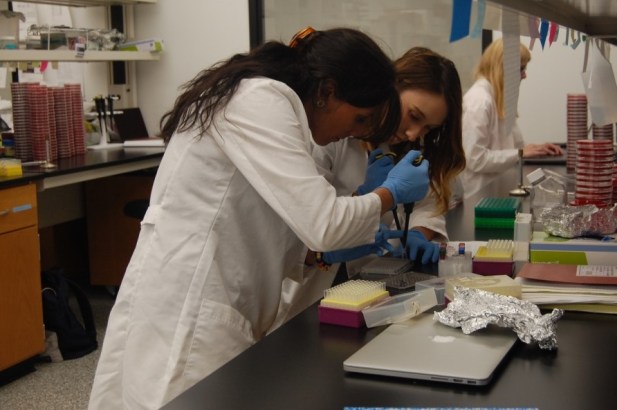

In one such scene, Dr. Monica Cartelle Gestal and her assistant are using pipettes to put something into hundreds of tiny cubes of fluid in short rectangular trays.

Files, folders, and giant notebooks are pushed to the edges of long work benches covered with petri dishes. Vials and tubes line up along the shelves, and beakers with boiling chemicals and large machines with big windows fill the room, where the gloved lab techs examine pathogens in isolated environments.

It smells like a hospital — cool and sterile but with the faint odor of sickness.

The lab’s target is Bordetella pertussis, also known as whooping cough. Gestal is using her understanding of bacterial communication to help the principal investigator, Dr. Eric Harvill, create a safer and more effective whooping cough vaccine. It is no easy task.

Gestal began her scientific work in Spain, where she was recruited to work in a clinical microbiology facility, running diagnostics for every illness imaginable in a lab that works with up to 500,000 cases at a time. Six months later, she was immersed in epidemiology, identifying anti-viral resistance in HIV patients as well as tracing and controlling antibiotic-resistant bacteria in hospitals across Spain.

“I always wanted to do science,’’ Gestal says. “Even before high school. I was taught microbiology and it just got me. I knew from 11 or 12 years old that I wanted to dedicate my life to try and control infectious diseases.”

That’s what got her interested in bacterial communication, something most people barely know about.

It’s a real thing. When we are sick, there is a tiny war inside of us. Bacteria can communicate on where and how to organize as well as when to hide and when to attack.

Gestal explains the process, known as “quorum sensing.”

“Bacteria communicate with each other via small signal molecules, which are basically chemicals. They can actually coordinate behavior to do something beneficial to them and really [to] our detriment.”

The investigation of quorum sensing eventually took her to Ecuador, a small South American country with some very big mountains. There she worked first in a tiny village on the side of a 19,000-foot volcano. Then she moved down to the bustling capital, Quito, a city which itself has a higher elevation than any U.S. peak east of the Rockies.

While in Ecuador, Gestal was invited to run the National Reference Laboratory for Antibiotic Resistance. She collaborated long distance with a microbiology team in Romania, identifying how nano-compounds, such as silver or peppermint, make antibiotics more effective by helping them get inside cells and release their agents more slowly.

The work on nano-compounds had fruitful results, and led to multiple publications as well as an ongoing partnership with Romania. Before leaving South America, she offered her services to the front lines and worked as a consultant for the Ecuadorian Ministry of Health.

Upon returning to her research, she realized her next step. She needed to learn how bacteria communicate with their hosts, which meant using animal models. That is what brought her to Harvill’s lab at the Center for Vaccines and Immunology at the University of Georgia.

Whooping cough refuses to disappear

Pertussis has been a health problem since ancient times, but major progress against it began to be made in the early 20th century. (Dr. Leila Denmark, a Georgia pediatrician who later became famous for her extraordinarily long life, was among the pioneers in developing an early vaccine.) Unfortunately, the disease has not vanished, and research toward a new vaccine is a scientific priority.

During 2016, state health departments reported 15,747 cases of pertussis to CDC. Infants are frequently the most affected by whooping cough, and one out of every 100 infected infants who are treated at a hospital die of the disease.

The CDC reported 170 cases of pertussis in Georgia in 2016, which was below the national average. But while the national average has decreased in the last few years, the number of cases in Georgia has more than doubled since 2013 and is still increasing.

Nationwide, pertussis has become more pervasive in adolescents. To combat this, the Georgia Department of Public Health began requiring yet another diphtheria, pertussis and tetanus (DTaP) booster for 7th-graders as of 2014. Health professionals know that this well help, but it is not a silver bullet.

Although the vaccine is working, there is room for improvement. The CDC reported that about half of children in the United States who contracted pertussis were already fully vaccinated.

According to Dr. Glen Nowak, previous director of communications for the CDC’s national immunization program, the original pertussis vaccine has an interesting history in the United States.

“The wholesale pertussis vaccine was highly reactive, which meant that people who got it mounted a pretty strong immune response, which is actually a good thing, but it made people’s arms sore, it gave kids fevers,’’ says Nowak, a UGA professor specializing in risk and health communication. “And parents don’t like even minor side effects or reactions.”

The vaccine became a controversial issue for the American public in the 1980’s. “The other thing that happened to the wholesale pertussis vaccine became the source of a lot of accusations of severe adverse effects involving brain injuries,’’ Nowak says.

A new pertussis vaccine was developed that was much less reactive, but also less effective.

“Children get at least four DTaP vaccinations and there is still concern that the fourth vaccination may not protect into late adolescence,’’ Nowak says. “[But] continuing to add doses of DTaP s is a little problematic.”

According to the CDC, the pertussis vaccine is available only in a combination shot with tetanus. This means that every time children get booster shots, they are getting a generally unnecessary tetanus vaccine.

“People are pretty confident that it doesn’t cause harm [to include a tetanus vaccine] but there is no benefit . . . you don’t need boosters of tetanus that frequently,’’ Nowak says. “So there is a lot of interest in developing a new pertussis vaccine.”

Will public acceptance be a problem?

Harvill and Gestal are trying to create an attenuated live vaccine.

That means they want the vaccine to have a very weakened live strain of pertussis, which the body can defeat entirely and thereby develop a permanent immunity. The way the vaccine works now, children’s immunity to pertussis wanes after only a few years, and they frequently need boosters.

Also, the immunity that children receive from the current vaccine does not stop them from spreading it to non-vaccinated populations. While the current vaccine prevents the symptoms (toxins) of bacterial infection, it does not stop “colonization” of pertussis within the vaccinated person’s body.

Oftentimes, vaccines that involve live viruses cause people more public worries about safety.

“If the vaccine generates the stronger initial immune response, you might be back to some of the reactions you saw with the wholesale pertussis vaccine,’’ Nowak says. “Some of these goals are difficult to achieve. If they can pull that off, that would be amazing.”

Gestal feels confident that in the years to come, her team will find the answers they are looking for.

“We have to play detective,” she says.

“You do a lot of experiments because you are trying to answer a question, but if you pay enough attention, and you don’t just look, but observe, you find a lot of things.”

This is the part of the process that grips her:

“I love all the little things that appear when you ask a question that are not your answer but are the things that lead you to the next question.”

“A scientist that comes to the lab to find one answer is limited. The mind has to be completely open to find the most stupid thing. . . . [Alexander] Fleming found penicillin because he left his plates on the bench and went on summer holiday. When he came back, they were contaminated with fungi. Another person would have thrown them in the bin, but he actually bothered to check. And then slowly, slowly, that’s how he discovered penicillin.”

The pertussis team has a long road ahead. In order to go from the lab to the shelf, vaccines undergo a rigorous investigation period that lasts 10 to 15 years. First lab mice, then cats, then a small human trial, then medium trial, then a large trial, all with very stringent intervention and re-evaluation by the FDA. After that, the CDC runs its own round of quality assurance before making a recommendation.

What does it mean for scientists everywhere waging the microcosmic war against viruses and bacteria? A lot.

The vaccines they are developing today will be for the next generation. If they go through their process of legitimization without a hitch, the grandchildren of some of today’s researchers will receive the shots.

Gestal and other scientists are well aware of the commitment they have made and don’t dread the journey in front of them.

“I love my job . . . it’s fascinating,’’ she says. “It keeps me young because my mind is always working.”

Advocate of human wellness, critical thinking, and global perspectives on local issues, Dannie Parker is an educator, writer and media researcher currently residing in Athens.