By Andi Clements and Andy Miller

Dr. Robert Price’s routine of going to work and coming home used to be drama-free and pretty ordinary.

Price, an emergency physician at Piedmont Athens Regional Medical Center, would leave through the front door of his house, and he would return hours later to be greeted by hugs from his five children.

That was before the COVID-19 pandemic.

Now when he gets home, he goes straight to the basement.

“It’s impossible to leave a hospital without touching anything,” said Price. “So, the easiest place for me to start sanitizing myself is in my basement. And then I know nothing is contaminated when I go up into the house.”

Health care workers across the state and nation who are on the front lines in fighting COVID have taken extraordinary steps to protect their families and friends. There are waterless hand wash products that can help not just health workers but everyone who wants to protect themselves and their families from the virus.

The coronavirus has infected tens of thousands of these workers, so the fear of spreading the disease to loved ones is all too real.

Nearly 600 health care workers in the U.S. appear to have died of COVID-19, according to Lost on the Frontline, a project launched by The Guardian and Kaiser Health News. The count includes doctors, nurses and paramedics, as well as crucial health care support staff such as hospital janitors, administrators and nursing home workers, who have put their own lives at risk during the pandemic to help care for others.

In Georgia, data from the Department of Public Health show that about 10 percent of the cases of COVID-19 infection are among medical workers, but the state acknowledges that this figure may be low. Some medical personnel in the state have died of the disease, but how many is not known.

Price’s safety regimen includes setting up a dirty zone and a clean zone in the basement bathroom where he enters the house.

He’s careful to touch only certain parts of the shower curtain before scrubbing off possible contaminants. After showering, he uses bleach wipes to clean every surface he touched, taking care to include doorknobs and light switches.

Then he places all personal protective gear — like his cotton surgical cap and goggles — in a basket to be laundered and sanitized.

He has trained himself to make this whole process habitual, almost instinctive.

“I’m trying to make it a routine,” Price said. “Because, when you finish a shift at 2 a.m., it’s really easy to forget. You have to be really cognizant of where your hands have been.”

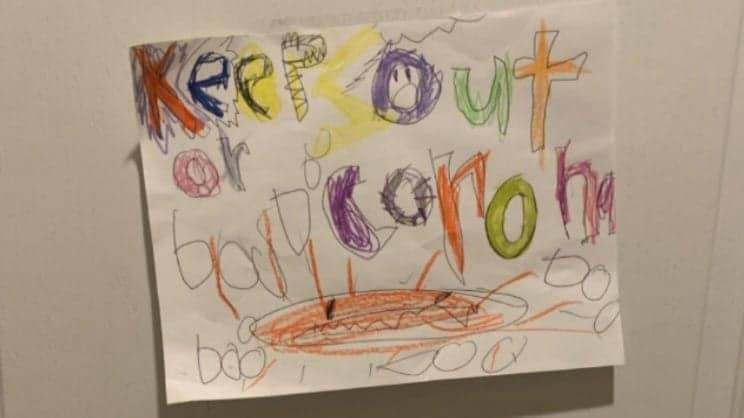

Even his family members know the rules. Price’s car, which is used only to transport him to and from work, is called the “COVID car.”

“My kids know that my car and the basement bathroom are off-limits,” Price says. “We’ve made signs to hang on the outside of the door to remind them.”

Family life disrupted

Nurses and other medical providers are following similar precautions.

A large number of nurses and other health workers are living in self-isolation, cut off from their loved ones during the pandemic.

Many health care providers have been sleeping in basements, campers, hotel rooms, backyard tents, and even in their cars after their shifts instead of returning to the comforts of home, a Daily Nurse article said in April.

Others, who have no choice but to continue to live at home, go through meticulous procedures to decontaminate themselves — stripping off their work clothes in the garage and taking long showers before allowing themselves to have any contact with family. Some sleep in separate bedrooms from their spouses. Where possible, some have a separate bathroom that no one else uses.

Carey Lamphier, a metro Atlanta nurse, had to develop a new routine with cars and entry into her home.

The car she drives to work is the one that she wipes down when she gets back from work. And that’s the only car she uses.

“I use our garage for changing,’’ Carey said. “I run up the stairs straight to take a shower. Then I can take those clothes and they go straight into the washing machine.’’

“We sort of came up with the concept of the dirty car and the clean car and it really worked for us. Our son [six years old] has never been in the dirty car’’ since the pandemic began, she says.

“And I wipe it down frequently, like how I wipe the house down all the time.’’

When she comes home, she can’t hug her husband and son as soon as she arrives. “That’s really hard for me,’’ she acknowledges.

Doctor, mom, and now teacher

Parenting is another challenge for medical providers during COVID-19.

Dr. Keisha Callins, the only ob/gyn and on most days the only physician in rural Twiggs County, talks about having to educate her two children during the pandemic because schools have been closed. “It has been a life-changing experience, but my husband and I were fortunate to be able to make some short-term changes in our schedule to assist with daytime classwork,” she says.

Callins, like other providers, worries about bringing COVID-19 home to her family. She often changes clothes and shoes before leaving the office or showers after arriving home.

There’s an increased concern about physician burnout during the pandemic. Even before COVID struck, a 2017 study by the Mayo Clinic discovered that the burnout rate for physicians in the United States was nearly 44 percent.

The stresses now have increased for many on the front lines.

Callins is chair of the Medical Association of Georgia’s Physician Resilience Task Force, which is evaluating physician burnout. It recommends ways to help physicians and other health care workers avoid burnout and assist health systems in dealing with its consequences.

“Although providers are stretched to a whole different level, we are natural leaders and must continue to rely on our inherent resilience as we take care of our patients, our staff, and ourselves,’’ Callins says.

A dad at a distance

Since the pandemic began, Dr. Frank Lin, a neurosurgeon at Wellstar Kennestone Hospital in Cobb County, has not gone home at all.

At least, not inside the house.

He and his wife saw the pandemic’s effects coming and developed their own protection plan for their family. “As a trauma and stroke neurosurgeon, I’m constantly in the ER and ICU,’’ he says.

Lin has been staying in hotels for months. “I have not been in my house since March 13.’’

Lin does the grocery shopping for the family. “I’ve been kind of the runner,’’ he says.

And parenting is a bit more remote: “I see my kids across the fence.”

Birthdays have taken logistical planning. The family set up tables outside for Lin’s birthday. His kids’ birthdays were celebrated outside, too.

Lin and his wife are now trying to figure out when he can come back inside.

He may have to wait a while longer. There are still COVID-19 cases coming into WellStar Kennestone, he notes.

But he has a goal: “I would like to be home before school starts.’’

Freelance journalist Judi Kanne contributed to this article.

Andi Clements is a public relations graduate student at the University of Georgia. She received her bachelor’s degree in economics and is interested in business and non-profit sustainability. She has a portfolio at https://andiclements.wixsite.com/mysite