This Commentary was first published by the Philadelphia Inquirer

By Fatima Syed, Deep Shah and Ravi Parikh

Just a few months into the COVID-19 pandemic, many U.S. physicians feel that they are at war. War metaphors are now being invoked across the country. The president of the United States even declared himself a wartime leader. Media outlets now make regular reference to physicians as “front-line soldiers” who go “into battle” on a daily basis.

As practicing physicians just out of training – physicians who have never practiced in war or during a pandemic – it is easy to picture ourselves as warriors, donning whatever equipment we can and taking a deep breath before we enter the hospital and clinic.

But unlike traditional wars, this battle extends outside of the battlefield. These soldiers do not sleep in trenches; they return home each night. Their babies need to nurse. Their partners may be soldiers who also need relief.

Each trip home requires a renewed commitment to containment — to isolate their families from the disease that they have spent the day fighting. Sometimes, it is easiest to isolate themselves. Anything to avoid exposing their families to the invisible enemy they are fighting and may have even contracted. Yet they continue to fight, because that’s what they signed up to do. It is their solemn duty, an oath they took with their fellow soldiers. “Dulce et decorum est pro patria mori.” (It is sweet and fitting to die for the homeland.)

But unlike the U.S. military, many of us are going to battle without appropriate armor or ammunition. We want to help. But we never signed up to die.

Frontline healthcare workers include the physicians, nurses, emergency responders, respiratory therapists, and other staff that will take care of the tens (if not hundreds) of thousands who will be affected by COVID-19. The battleground is our communities, hospitals, clinics – and, unexpectedly, our homes.

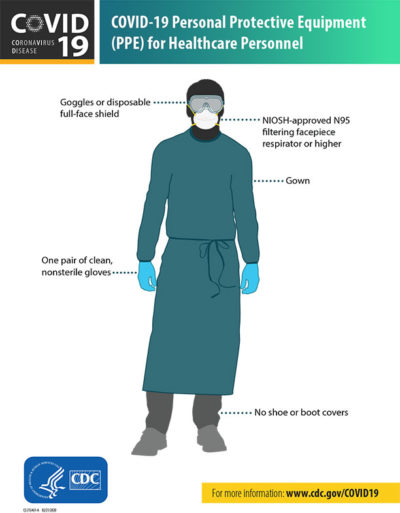

We are terrified to work in facilities that lack the environmental controls and personal protective equipment (PPE) needed to protect us and our babies, parents, and sick family members and patients. What if we bring the virus home?

When it comes to PPE, we are witnessing a national shortage, a great deal of intrahospital rationing, and repeated violations of “do no harm” – to ourselves and families. For reasons that remain unclear, physicians have suffered a higher death rate than the general population in countries ravaged by COVID-19. In the face of these developments, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) released guidance stating that as a last resort, doctors might protect their faces with bandanas.

This official statement has been interpreted in physician circles as a quiet surrender. The country may not beat this virus, and healthcare workers may not be protected in this defeat. And if we fall sick to the illness – or worse? We’ve been coerced by a new hidden curriculum, compelled to adopt a soldier’s mentality that dying on the battlefield is better than being labeled a deserter.

Yet there is a belief in each person who chooses to be a doctor that the fortitude that guided us through training will lift us and our patients out of this war.

Just as soldiers have advocated for appropriate military equipment, we can advocate for appropriate PPE. We can draw precedent from wartime efforts.

From February 1942 to October 1945, a presidential order through the War Production Board stopped production of cars, trucks, and auto parts. Overnight, for the sake of the war effort, an entire industry was repurposed to conserve industrial materials and promote mass production of military transportation, weapons, and combat armor to help win World War II.

Federal leaders today are encouraging but not requiring capable manufacturers to produce PPE for medical personnel. This strategy is unlikely to achieve the target goal of producing 3.5 billion masks a year during pandemics like this one, and would be essentially impossible to do in time to deal with the incidence expected by the summer of 2020.

We as physicians and health care workers should partner with our patients in a broad education campaign about the necessity for PPE, and the sacrifices we may have to make to ensure adequate supplies.

A cooperative effort might also help restore the trust between patients and physicians, which has eroded over the last several decades with the commodification of health care.

Initial strategies may include:

- Applying lessons from successful public health campaigns for screening mammograms and influenza vaccinations, to cultivate widespread and lasting support for PPE production and adherence.

- Continue to share stories with patients and media, about how lack of PPE will exacerbate community transmission of COVID-19.

- Encourage patients to call their lawmakers to emphasize that PPE ranks among their top concerns in the upcoming elections.

- Explain to patients during every visit that PPE for physicians and health professionals protects everyone in the community, akin to vaccines.

Imperial College London recently published an analysis indicating that the war on COVID-19 will last 18 months, maybe more. So what happens in long wars? Citizens rally around the soldiers. We now need our patients as much as they need us.

As early career physicians, we worry that many of our colleagues – strapped by student loans and the costs of starting a practice – may exit the profession far too early. We need our patients to hold policymakers accountable for lessons already learned from the COVID-19 crisis. And most importantly, we need them to advocate for wartime production of PPE.

Otherwise, the scars of this war will mark us for the rest of our careers in medicine.

Fatima Syed is an internist in Durham, N.C.; Deep Shah is a community primary care physician in metro Atlanta; Ravi Parikh is a medical oncologist at the University of Pennsylvania and at Corporal Michael J. Crescenz VA Medical Center in Philadelphia.