Brenda Goodman is a senior news writer for WebMD. Andy Miller is editor and CEO of Georgia Health News.

Updated Friday

A medical sterilization facility in metro Atlanta is shutting down operations until October as it undergoes construction to reduce emissions of a toxic gas.

Sterigenics said Friday that a September shutdown will expedite the improvements that the company has promised state officials that it will make to reduce ethylene oxide pollution.

The move comes as a coalition of the Cobb County, Smyrna and Atlanta governments has installed monitors around the Smyrna plant to begin testing airborne levels of ethylene oxide, a cancer-causing chemical released during the sterilization process.

Separately, the Georgia Environmental Protection Division (EPD) had planned to begin its air testing for ethylene oxide in October.

Residents are worried that any air testing conducted now would not reflect what has historically been released during normal business operations.

“It is extremely suspicious given that the company told us it couldn’t be done,” said state Rep. Erick Allen, who represents the Smyrna area.

In recent public meetings, Phil Macnabb, president of Sterigenics, told residents he would not shut down the facility while improvements were made because doing so would disrupt the supply chain for medical devices in the United States. He said more than 1 million medical products are sterilized at the facility each day.

“If that’s now on the table, I think a long-term closure should be re-evaluated,” Allen said.

In a related matter, state Sen. Jen Jordan and two area residents filed a lawsuit asking a Fulton County judge to throw out a consent order on the Sterigenics construction plan that the company reached with state officials in August.

Jordan, a Democrat who represents part of the Smyrna area, said Friday that the consent order between the state EPD and Sterigenics was negotiated behind closed doors and executed without making the public or elected officials aware of it. State law requires the EPD to allow for a period of public comment on consent orders, the lawsuit says.

“If members of our community had been allowed to be heard, what EPD and Sterigenics would have agreed to would have looked very different,’’ Jordan said. She cited what she called a stronger agreement between the company and the state of Illinois, where Sterigenics operates a sterilizing plant that has also been the target of public outcry. The Illinois agreement requires air monitoring, limits on the amount of ethylene oxide the facility can use each year, and strict emissions limits.

The office of Georgia Gov. Brian Kemp referred a reporter to the state attorney general’s office for comment on the lawsuit. A spokeswoman for Attorney General Chris Carr, who will defend the state in the case, told GHN that she was unable to comment on pending litigation.

Many residents in the Smyrna area have been rattled by reports about ethylene oxide emissions from the sterilization plant, including a previously unreported leak in July.

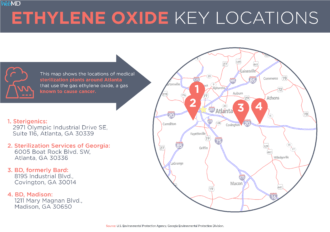

The toxic pollution issue in Georgia came to light due to a report published last month by WebMD and Georgia Health News. The report said that last year, the federal Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) identified census tracts in the Smyrna area, just northwest of Atlanta, and in Covington, about 35 miles east of Atlanta, as among 109 nationally that had increased cancer risks, largely due to the use of ethylene oxide.

Covington also has a sterilizing facility, run by BD Bard, which uses ethylene oxide.

Groups in the Smyrna and Covington areas, where residents first heard of the ethylene oxide problem from the news report, held town hall meetings where scores of residents called for air testing. Both local governments and the state EPD announced plans to test the air around the two medical sterilizing facilities.

Sterigenics had already been cutting back its sterilization processes during the initial construction that the company said would reduce ethylene oxide releases.

Ethylene oxide is used on about half the medical devices that require sterilization, according to the Ethylene Oxide Sterilization Association. The chemical was classified as a cancer-causing substance in 2016 by the EPA.

“The construction is proceeding ahead of schedule,’’ said Sterigenics in a statement Friday. “We have determined that suspending sterilization operations, and the use of [ethylene oxide] in those operations, throughout the duration of the work will enable us to further accelerate the installation of these enhancements and that doing so is the most efficient path to meeting the requests of all stakeholders.’’

The company also said that it “is also working with customers to minimize the impact on the supply of vital sterile medical products to hospitals and the patients who depend on them every day.”

But Kemp’s office late Friday criticized Sterigenics’ move. “Shortly after the state opened an investigation into an unreported evacuation of the Sterigenics facility in Smyrna, the company fully suspended operations — despite its initial refusal to do so — to focus on the installation of new, emission-reducing equipment,” said a statement from Candice Broce, a spokeswoman for Kemp.

“Because the company has struggled to operate with adequate transparency, we have reservations about this new proposal. Inexplicably, state officials were afforded almost no time to vet its feasibility before the company announced it,” the statement continued. “We have gathered new information through the course of the state’s ongoing investigation. We will withhold judgment on today’s announcement until we can independently assess the proposal. The safety of Georgia families remains our top priority.”

Bridget Kurt of the activist group Stop Sterigenics – Georgia said Friday that the sterilization hiatus at Sterigenics would skew the air testing results.

“We need accurate data of the amount of EtO [ethylene oxide] being emitted into the air when Sterigenics is in full production,’’ Kurt said. “Air testing conducted while the plant is shut down will not give us the data we need.’’

Ethylene oxide lasts for months in the air but it is not a stationary mass, Kurt said, adding that the gas moves, disperses and is affected by weather.

Jordan also questioned the timing of the shutdown as air testing is beginning. “It clearly seems like it’s intended to avoid people knowing how much ethylene oxide they’ve been emitting,’’ she said. “They don’t want to get caught .’’

The lawsuit, she said, targets what she called a lack of public protections in the state’s agreement with Sterigenics.

“The consent order limits what Sterigenics has to do,’’ Jordan told WebMD and Georgia Health News. “What’s contained in the consent order is nowhere near the place where appropriate remediation has occurred.’’

In Illinois, where leaders in government pushed much harder, the consent order with Sterigenics contains important protections, Jordan said.

“The [Georgia] consent order as it stands is a bad deal. I’m trying to give the state the ability to do it over and do it right,’’ she said.