By Chris Herbert

On a street in downtown Athens, across from an arthouse movie theater and beside a craft brewery, sits an off-white building with a large statue of a bulldog near the entrance. This structure houses a local branch of Biotest Plasma Center, a national company that collects plasma from people’s blood.

Plasma, when it’s separated from the rest of the blood, is a yellowish liquid. It is rich in protein and helps the body to fight infection. It is so valuable for pharmaceutical companies that it has sometimes been referred to as “liquid gold,” according to the National Institutes of Health.

The American plasma industry has become a massive business with centers across the nation. Patients lounge on beds watching television as their plasma is extracted. The process involves drawing blood, separating out the plasma and returning the rest of the blood to the person’s body.

“We stay pretty busy,” said Colby Chapman, who handles donor services at the Athens Biotest center. It handles dozens of donations per day, and is one of the busiest centers in the Southeast, he said.

The growing popularity of plasma donation is troubling to some medical ethicists, who are concerned that donors may not fully understand the value of what they are giving up.

Even the use of the term “donation” raises questions for Arthur Caplan, a professor of bioethics at New York University, because the people who give plasma in this country are compensated. In Athens, for example, they receive prepaid debit cards, which are reloaded after each donation.

The language of the industry “sort of rides on the notion that this is a kind and altruistic activity, where, in fact, it’s a pretty big commercial business,” said Caplan. He pointed out that in many other countries, people give their plasma free for medical purposes.

Unlike whole blood, which is transfused directly into a patient’s body, plasma can be sold by organizations like Biotest to pharmaceutical companies that use it to produce drugs. Biotest’s website lists a number of plasma-derived medical products, including albumin (which is used on burn victims), and vaccines for tetanus and rabies.

A study published in 2012 in TRANSFUSION, a peer-reviewed journal, assessed the uses of plasma-derived medicines and found they aid burn patients, patients in shock and patients with clotting problems. Another study, published in 2016 called plasma a “strategic resource,” categorizing it as a material as valuable as drinking water or energy.

The Plasma Proteins Therapeutics Association, a global organization that advocates for the plasma industry, released data in 2017 showing that more than half of plasma donors were between the ages of 18 and 34, while older donors, ages 35 and above, tended to donate more consistently.

While the Biotest Center in Athens is just a few blocks away from the University of Georgia, students are not the facility’s largest donor population. According to Chapman, the majority of the local donors are between 30 and 50 years old.

How the business works

A visit to donate plasma is not a simple in-and-out process.

Precautions must be taken to ensure donors have sufficiently healthy plasma. Employees administer a series of questions and tests before each visit to certify a person’s health. When people enter Biotest, they check in at small electronic kiosks and answer a list of about 60 questions about their current health status, such as current medications, recent travel, recent sexual history and other medical issues. (For instance, pregnant women cannot donate blood or plasma.)

The donor is then weighed to determine how many units of plasma can be given on that day.

After another waiting period, staffers take the donor’s blood pressure and prick the donor’s finger to check protein and iron levels. If these levels are in the proper ranges, the donor is allowed to give plasma that day. The amount extracted depends on the person’s weight and hydration level, Chapman says.

After the donor lies down on a bed, a staff member will insert a needle and starts a machine to begin the donation. The machine extracts the donor’s blood, separates the plasma from the blood by a process called plasmapheresis and returns the separated blood back into the donor’s veins.

Drinking enough water and eating healthy foods the day of the donation helps keep the blood from becoming too viscous. Thickened blood can interfere with the donation process.

After the donation, the day’s pay is placed on the person’s card.

Biotest recruits donors through financial incentives, social media and word of mouth.

Chapman has increased the location’s presence on sites like Facebook to engage with more donors. The location’s Facebook page contains testimonials from patients who benefited from plasma as well as news and information about promotions for donors.

The most effective recruitment tool is increased payment during the early visits.

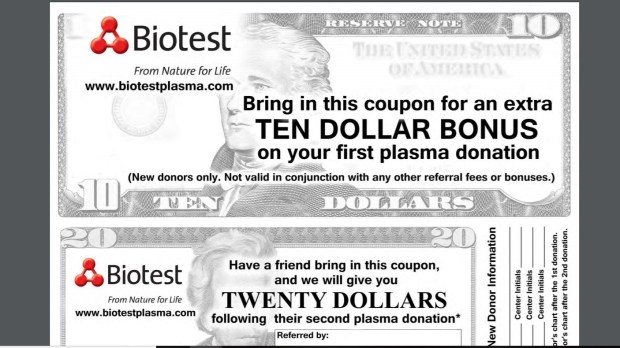

A person receives $50 per donation for the first 10 visits. The initial visit can rise to $60 if the donor prints out a coupon from Biotest’s website. Another coupon offers $20 extra for referring a friend.

After the first 10 visits, donors receive $30 to $40 each time, based on a payment schedule.

In an effort to promote more donations and help in the community, the Athens location started a food drive in November that is still ongoing. Initially started as a holiday food drive, the organization collected over 2,000 pounds of food in November and December by offering small bonuses for bringing cans of food to the center.

The compensation can be a financial stopgap for some people. That was initially the case with Daniel Dewitt, a 40-year-old donor from Monroe, who learned about Biotest from a friend on Facebook. “When I was out of work, that kind of gave me some of the extra money I needed to hang on . . . until I found another job,” said Dewitt.

Like Dewitt, Rose Rogers, a 61-year-old caregiver from Watkinsville, started donating during a stretch of unemployment, but both returned to donate mainly because of the desire to help. Both are now financially stable, but each uses the money as a vacation fund.

“It’s just so convenient since it’s put on a card,” said Rogers.

Others, like Christopher Kubiak, 34, of Jefferson, heard of Biotest from a friend. He got into a discussion about plasma donation after mentioning that he liked to give blood. “I’ve been wanting to give plasma for a while, and I didn’t even know I could make money,” he said.

Out of step with the world?

Caplan, the bioethics professor, noted an irony in the plasma business. “A lot of the world doesn’t pay plasma donors,” he said. “They’ve taken the moral position that it’s wrong. They just import their plasma from us.”

This situation demonstrates the need for an international agreement about how to regulate plasma, according to Caplan.

Chapman of Biotest has his own take on the international situation. He said the U.S. share of the world’s plasma supply is 94 percent, and the reason is quality. “Overall, we’re healthier,” he said.

He acknowledged that people who walk into Biotest are compensated, as at other U.S. centers. But he noted that blood is sold off wholesale like plasma, even though blood donors are not paid. “[To] get paid for something is kind of weird to people,” he said. “But basically, we’re compensating you for your time.”

Caplan and Chapman disagree about the situation in the U.S. plasma industry.

Caplan said he worries about a lack of transparent research done on plasma donations. Blood as a biological material is overseen by regulatory agencies like the FDA. Also, the Red Cross shares blood supply information with researchers.

On the other hand, Caplan said, plasma is considered more of a commercial product, receiving less attention from regulators. “It’s more secretive,” he said.

Chapman, however, said there is ample oversight of the plasma industry. “We’re heavily regulated by the FDA, and not only FDA, but multiple other organizations,” he said.

Donors interviewed for this story seemed unfazed by the business aspect of the plasma industry and emphasized that for them, donating is about helping others.

“It’s strictly for charity. I like the fact that I’m helping someone,” said Rogers.

“Don’t do it for personal gain,” Dewitt advised potential donors, “but do it because you want to. Because you have a heart to do it.”

Kubiak feels he’s doing good for others. “If you’re looking for a purpose – a way to help – there’s a ton of burn victims who can use plasma,” he explained. “You won’t know who it goes to, but you know it’ll bring someone joy.”

Chris Herbert is a freelance journalist and graduate student at the University of Georgia. His interests lie in health, investigations, content moderation, security and privacy. Chris’s previous work has appeared in Yahoo!