Tresa Haywood, 50, has had a complicated medical history in recent years.

She was diagnosed with Hashimoto’s disease, an autoimmune disorder, in 2000. Two years later came a diagnosis of diabetes, followed by diagnoses of hypoxia – low oxygen in the tissue – irritable bowel syndrome and other conditions in 2004. She was even believed to have cancer at one point.

It was not until 2012 that her doctors did genetic testing to find the root cause of all her conditions. She finally received a diagnosis of hemochromatosis — something she had never heard of.

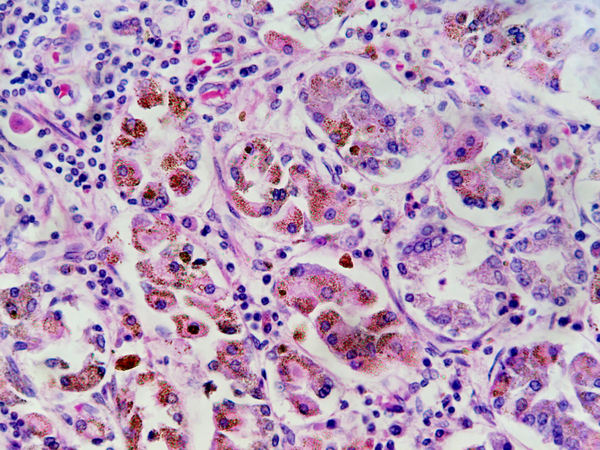

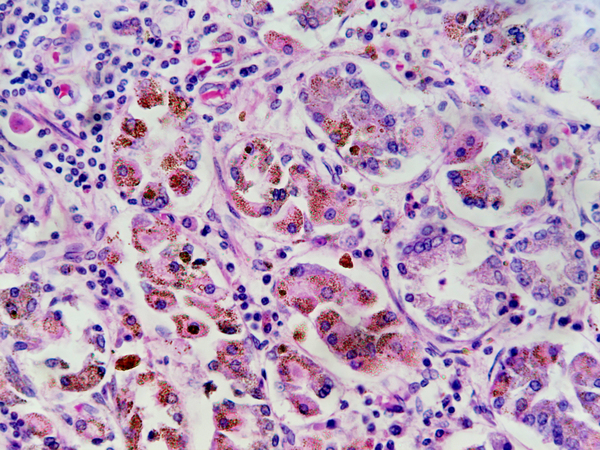

Hemochromatosis is a disorder “in which the body can build up too much iron in the skin, heart, liver, pancreas, pituitary gland and joints,” according to the CDC.

“Patients with hemochromatosis can have problems with iron overload in the liver, and it can affect other organs in the body like the heart, the joints,” says Dr. Bruce Bacon, a St. Louis-based liver specialist, whose areas of expertise include hemochromatosis.

It’s a very common genetic trait, says Dr. Brian Pearlman, medical director for WellStar Atlanta Medical Center’s Center for Hepatitis C in Atlanta. But in order to develop the disease, a person must inherit the trait from both parents.

Iron is one of the major chemical elements on Earth, and a proper level of it in the human body is necessary for life. Most Americans have probably heard about iron deficiency, a serious problem for many poorly nourished people. But hemochromatosis, which is sort of the opposite condition, is less known.

Hemochromatosis causes the body to store too much iron, which can lead to serious health problems.

“It’s predominantly a disease of Caucasians,” Bacon says. The CDC states that 1 in 300 non-Hispanic whites in the U.S. have hereditary hemochromatosis, although many of them may never develop symptoms or complications. The rates of the disease are lower for other races and ethnicities.

Pearlman, a hepatologist who treats patients with the disorder, explains in simplified terms what hemochromatosis does to people: “A normal person has ways to absorb the iron, and has a ‘brake’ for iron to prevent it being over-absorbed,” he says. “If you happen to get the disease, your . . . brakes are not working and so you absorb a huge amount of iron.”

“The biggest advance with this disease has been we now have a genetic test which is commercially available,” he says.

Deceptive symptoms

Haywood, who lives in Hampton, saw a doctor who believed that she had cancer. That doctor sent her to a hematologist/oncologist, who did blood work and found that she had two hemochromatosis gene mutations. By the time she was diagnosed in 2012, she had suffered damage to her kidneys and liver.

The most common treatment for hemochromatosis is phlebotomy, or taking blood from a person. That reduces the individual’s iron levels. “If I was to take a pint of blood from you for a blood drive, that would reduce your body iron storage by about 200 milligrams of iron. So treatment is by taking blood,” says Bacon.

Haywood has to have blood taken every five to six weeks to manage the disease. Obviously there’s a limit to how much blood can be drawn, and her treatment is further complicated by the fact that she also suffers from polycythemia, a type of blood cancer.

Hemochromatosis has affected her negatively in a number of ways. She has no appetite but still gains weight and retains water. She has no energy and has “brain fogs.”

Haywood has tried a number of natural methods to try and help her hemochromatosis and other conditions, such as changing her diet and doing herbal cleanses for her liver and kidneys. She also got “a natural cure, if you want to call it that,” from an American Indian reservation, which she believes helped to slow the hemochromatosis down, before the polycythemia took over.

She didn’t know what the disease was when she was first diagnosed, but it turned out that both her parents suffered from undiagnosed hemochromatosis. One of her sons, and his daughter, have also been found to have one of the genes that can contribute to hemochromatosis.

Hemochromatosis is often diagnosed late. That’s because some of its main symptoms — such as fatigue and joint pain, and erectile dysfunction in men — often occur with other, more widespread medical conditions.

Pearlman notes an analogy used by doctors. “The expression in medicine is ‘You hear hooves,’ meaning animal hooves, and you think ‘horse.’ Why? Because there are so many more horses around. You don’t really think about a zebra because that’s relatively rare,” Pearlman says. In this analogy, conditions such as depression and anemia are “horses,” while hemochromatosis, which can cause similar symptoms but is less frequent, is a “zebra.”

Bacon agrees that the rather generic symptoms can make hemochromatosis hard to diagnose. The disease “doesn’t have very distinctive symptoms that make the doctors say, ‘Oh, you’ve got ABC because you’ve got XYZ,’ ” he says.

Delayed diagnosis of hemochromatosis can lead to a lot of complications. The problems can include things such as bronze diabetes, liver cirrhosis or heart failure, according to Pearlman.

He describes bronze diabetes as when a patient “develops diabetes because the iron infiltrates the pancreas and they develop bronze coloring to their skin because the iron infiltrates the skin.” Bronze diabetes is problematic because it is a very late manifestation of the disease, and the patient who gets it probably has advanced liver and heart damage.

Learning about the risk

Because of the genetic nature of the disease, tests can detect it early, before health problems get too serious. Fortunately, that’s what happened with Amy Payne, who describes herself as “one of the lucky ones.”

“It’s hard to diagnose because the symptoms are like you’re fatigued, you have joint pain, I would never know if I had hemochromatosis if I didn’t get tested [because of] my dad,” she says.

Payne, a middle school teacher and mother of four, knew that her father had the disease. She got tested for it and was diagnosed around 15 years ago when she was in her mid-30s. This early diagnosis has made the condition a lot more manageable for her than for others, and means that she has been able to avoid the serious health problems that can come with it.

She got one of the genes from her father, who has the full-scale disease, and the other from her mother, who is a carrier.

Payne, who lives in Acworth, is now in the maintenance stage of her hemochromatosis. Her doctor checks her iron levels every three months, and if they get too high, she has a phlebotomy.

She has avoided many of the problems that come with the disease, but does suffer from arthritis stemming from it and has developed a heart condition that could be related to it.

Although hemochromatosis is found equally in men and women, according to Bacon, there are particular issues for females. For instance, due to loss of blood during monthly periods, some women’s iron levels drop temporarily from excessive to below normal.

Payne notes that other things, such as pregnancy, can reduce women’s iron levels. But if a woman has hemochromatosis, treating her with iron in response to such a reduction can be risky.

“When I was pregnant with my fourth child, I got very anemic and of course they wanted to give me iron,” she recalls. She told them, “No, you can’t give me iron, I have hemochromatosis!’’

As she explains, “My iron was low . . . because the baby was getting all my iron. As soon as the baby was delivered, of course, then my iron went back up” on its own.

It was during this pregnancy that Payne found her current doctor, who helps her manage her hemochromatosis. Her iron levels are tested once a month. If she shows excessively high levels of ferritin, a protein associated with iron use in the body, she is immediately sent for a phlebotomy.

Payne’s awareness of the disease has led her to try to prevent her children from being harmed by it. “It’s strange because I have four kids, and every time I try to get them tested and the pediatrician has no idea even what to do, I have to tell them what to do,” she says.

Because Payne has the gene and her husband does not, she knows that all their children are carriers but don’t have the disease. Unfortunately, carriers can still “load” iron. Due to her son’s recent diabetes diagnosis, Payne is ensuring that he is tested for his iron levels as well.

Both Haywood and Payne believe that everyone should be tested to see if they are at risk. Haywood says testing in young children could prevent a lot of health problems later.

“I think all doctors should just test everybody’s iron panel,’’ Payne says. “A lot of doctors don’t know that you need to have a gene from the mom and a gene from the dad,” she said. “You have to educate them sometimes, you have to be your own advocate.”

Naomi Thomas is a GHN intern based in Athens. Her father was diagnosed with hemochromatosis about a decade ago, and he is currently managing his disease.