This article is written by Elly Yu, a WABE reporter, and is published with permission of WABE.

A lot of us have probably been to the hospital emergency room: For a broken bone, an asthma attack, the flu. Chances are, it wasn’t the best experience. Long wait times in crowded lobbies. Doctors hustling back and forth through the hallway. Cold, sterile rooms.

But that experience can be much worse if you step into the ER with a mental health emergency. And yet, Georgia’s emergency rooms are where patients often go during a mental health crisis – and at times, patients can be stuck there for days waiting for a space at a psychiatric facility to open up.

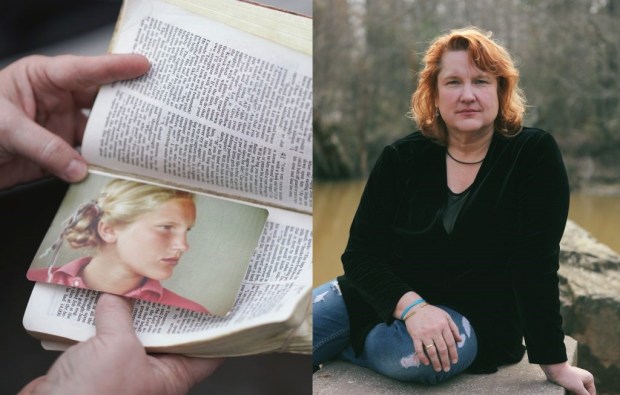

Ten years ago, Catherine Knight, a divorce attorney, was on her way to represent a client in court for an important trial. She was driving on Interstate 285 when suddenly she started to see and hear things she said she knew other people couldn’t see or hear. She pulled over to the side of the freeway.

“It wasn’t scary, but it was strange,” Knight said. “It was like a waking dream state.”

Knight’s had panic attacks before, but she said this time, it was something different.

“I don’t remember what I saw or heard but I knew it was weird, and I knew it was a psychotic break,” she said. “But I didn’t know the words for it exactly then.”

She was able to go home that day, but she never went back to practice law at that firm again – a firm she had helped to establish.

Knight had been diagnosed with bipolar disorder with psychotic features earlier in her life. She said she was able to hide her panic attacks before, but the incident on the freeway was a turning point.

“I was so ashamed, because I said thought, ‘well, that’s it. That’s the end’,” Knight said. “I worried about this day a long time because I’ve been vulnerable.”

Since that incident 10 years ago, Knight has been to the ER a couple of times.

In 2012, she was living in Gainesville and lost touch with those close to her, saying she felt ashamed about her mental illness. She said she was afraid to go out of the house – and then she started having psychotic episodes again. She remembers walking through the woods at night barefoot. At one point, she threw her cellphone in a pool saying she was afraid of it.

It got to a point where she wasn’t feeling well, and she eventually took herself to the hospital’s emergency room.

“I knew my brain wasn’t working right, and I wasn’t feeling well physically either, and I went into the ER – I feel like I had no shoes on,” Knight said.

She had a blanket that her grandmother had given to her when she was younger. She gave that blanket away to a woman who was cold.

Her memories of the ER are fuzzy – but she remembers how she felt.

“It was like I got isolated in a room,” Knight said. “It was scary.”

After staying in the ER overnight, Catherine was transported to a psychiatric facility in Lawrenceville, about 30 miles away. She said there was no room at the mental health facility at the hospital in Gainesville.

“At this point, it all starts to become like hell,” Knight said.

She spent four nights at a mental health hospital in Lawrenceville. She said the entire experience didn’t help. Two years later, she was in the ER again.

‘It’s probably the ER’s biggest problem’

In 2016, hospitals in Georgia saw more than 51,000 patients with mental illness, according to the Georgia Hospital Association. Yet, many hospitals don’t have psychiatrists in their ERs, especially in rural areas of the state.

At Dodge County Hospital in Eastman, the emergency room sees several patients a week who have a behavioral health crisis, said Miranda Bush, the hospital’s ER manager.

“We had three Friday,” Bush said. “Some are suicidal, homicidal; some are psychotic; some are off their meds; some are overdoses.”

There’s a seclusion room in this 11-bed ER that’s designated for behavioral health emergencies. The bed is in its own room and bolted to the ground. A camera hangs from the ceiling which allows nurses to watch a patient from their station. The room recently got a new door, after someone knocked it down, Bush said.

Bush is an emergency room nurse, trained to deal with trauma, but she acknowledges she’s not a mental health expert. Yet she is the one seeing patients, on a regular basis, coming into the ER.

“Sometimes I think [the ER] is the only place,” she said. “If they’re not appropriate for jail or they’re not appropriate for anybody else. People know we’re here for the community and we’ll do anything we can to help.”

She said they’ll do the best they can, but there are issues beyond their control – like the wait times for patients to get accepted into a psychiatric facility.

Dodge County ER Doctor Mark Griffis said an average ER stay for a patient is a couple of hours, but for a patient with a mental health crisis, it’s much longer.

“Almost all of them stay at least a day. And it’s real common for them to stay three or four. But we’ve had them as long as 10. I think 10 days is our longest,” he said. “But that’s a long time to stay in the ER – we don’t even have a shower.”

Bush said there are a few reasons mental health patients stay longer. First, there’s no psychiatrist in the ER, so the ER has to call up a mobile crisis unit, where responders who are trained in behavioral health will come to the hospital to do an assessment.

But the main reason for the long ER stays is that most patients are uninsured, which means they have to wait for a state-funded psychiatric bed to open up, she said.

“If they have good insurance, it’s usually not much of a problem to get them placed. If they’re non-insured or have Medicaid, it’s very time-consuming,” she said.

While mental health patients can wait for days in an ER, the wait also strains the emergency room’s capacity as a whole, Bush said.

“A lot of times, you’ve got patients sitting here for seven or eight days when you get sick people that you don’t have a bed for,” Bush said. “It’s probably the ER’s biggest problem. It’s our biggest, hardest obstacle to overcome back here –is mental health placement, by far.”

Last year, the average wait time to get accepted into a space in a state-run hospital was about 52 hours, according to the Georgia Department of Behavioral Health and Developmental Disabilities. That’s up from 42 hours in 2016. For those who are able to find a space near their community, the wait time is about 11 hours – that’s also been increasing.

Even when ERs in rural Georgia call to find a place, that placement can be hours away.

To get patients there, the county relies on its sheriff’s department.

Sheriffs: Transporting patients strains resources

Sheriff Lynn Sheffield of Dodge County is tall with gray hair. He sips coffee out of a large Styrofoam cup almost constantly. He said on average, the department gets a couple a calls a day related to behavioral health.

“There’ll be days we won’t have any at all, but then there’ll be days where we’ll have three or four calls with just mental health issues,” he said.

Deputies often take people to the ER during a crisis, but a big bulk of the department’s job is to transport behavioral health patients to psychiatric facilities. For a rural town, those facilities, are often hours away.

He said deputies can spend six to eight hours transporting patients to and from a facility.

“They’re not looking after the community when they’re doing that,” he said.

Sheffield said that’s a strain on a department with limited resources.

“We’re not paid for it,” he said. “We’re not reimbursed for any of it. It comes out of my budget.”

In 2016, deputies spent nearly 19,000 hours transporting patients, traveling more than 600,000 miles, according to the Georgia Sheriff’s Association. That’s data from just 87 of Georgia’s 159 counties reporting.

Dodge County Sheriff’s Chief Deputy Mike Patterson, who coordinates the schedules of deputies when they need to transport patients, said patients are usually accepted in Savannah at the state hospital there – about a 2 and a half hour drive away.

“They have to call around, now to get these folks accepted,” Patterson said.

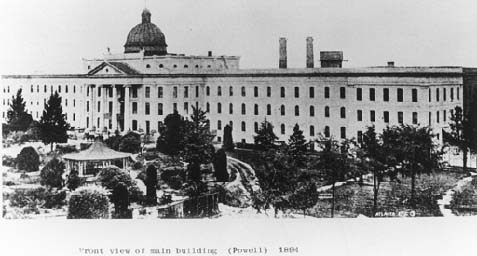

He said they used to take patients to Milledgeville – or Central State Hospital.

“Well you know, they shut Milledgeville down,” he said.

Shutting down Georgia’s mental hospitals

Central State Hospital in Milledgeville, also known as just “Milledgeville,” was once the largest mental institution in the country.

“My parents both grew up in Columbus, Georgia. And people would say to you ‘If you don’t behave right, you’re going to Milledgeville. It was like a colloquialism,” said Leslie Lipson, an attorney with the Georgia Advocacy Office, a group that advocates for people with mental illness and disabilities.

The hospital in Milledgeville closed most of its operations after the U.S Department of Justice sued Georgia for its treatment of people in state-run psychiatric facilities.

Lipson said there were a lot of problems at the mental institution in Milledgeville.

“There have been enormous abuses, both physical and sexual abuse, untimely deaths that happened in facilities, lack of medical care,” she said. “I mean, really, really horror stories.”

The state of Georgia settled with Department of Justice in 2010, agreeing to create more community-based services so that people can live and get mental health treatment near their homes.

But advocates like Lipson say this community mental health system has a long way to go to meet the needs of Georgians.

“I definitely think use of emergency rooms as psychiatric care for people with disabilities is an indicator of the failure of a community health system,” she said. “When you talk to people that end up in ERs for their psychiatric needs there were multiple pleas for help and people searching for services way before they get to that point.”

State: ‘The system is challenged’

The state agency tasked with creating a community-based mental health system is called the Department of Behavioral Health and Developmental Disabilities.

Judy Fitzgerald, the agency’s commissioner, describes it as: “Georgia’s public safety net for behavioral health and development disabilities.”

Since the 2010 Department of Justice settlement, she said the state has been working on building that safety net.

“The settlement agreement with the Department of Justice really challenged Georgia to say anyone who can live in the community and be served in the community should live in the community and be served in the community,” she said.

“That is really the thrust of our work. We’ve had a really intense buildup of community-based services.”

The state has until June of this year to meet the terms of that agreement. When asked about how advocates point to use of the emergency rooms as showing gaps in the system, Fitzgerald acknowledged there are gaps.

“I do think the system is challenged and the growing population in Georgia and growing needs with a large number of uninsured folks presents challenges for the public system,” she said.

She said she’s heard from Sheriff’s Departments and emergency rooms about the long wait and transport times.

“We really understand the challenge they feel,” she said. “The last place that we want a person in a psychiatric crisis to be is in the back of a sheriff’s car. So that’s really disheartening for us as well.”

Fitzgerald said the state’s psychiatric beds do get full. And Georgia, like many other states, has a shortage of mental health providers.

“We’re trying to build a provider network that can be responsive. But we do have workforce and funding challenges that we hope to continue to press and build,” she said.

One thing Georgia has been trying to do create crisis centers where people could go instead of the ER. But she said there’s more work to be done, for example in places like Rome.

A closed mental hospital and one solution

The state-run psychiatric hospital in Rome, Northwest Georgia Regional, used to serve more than a couple hundred people for mental health. It closed in 2011, after the Department of Justice settlement.

There’s a gate around the campus. It’s huge, about 130 acres. There are faded blue signs that used to tell people where to go for laundry, maintenance, a chapel.

Down the street from there is Redmond Regional Medical Center, a modern-looking hospital with a busy ER. Since the psychiatric hospital closed, officials at Redmond Regional said they’ve seen an uptick in emergency room visits for mental health needs.

On a Friday in January, the ER is bustling. Dave Tomey, director of emergency medicine at Redmond Regional, said the ER is a hectic place, and that when mental health patients wait for a psychiatric facility to open up, it can be difficult.

“[These] folks are just at a terrible time in their life coming to a place that’s busy, overworked and overcrowded, and they find themselves really needing a lot of time and attention,” Tomey said. “As an ER doctor and for ER nurses, they don’t have a huge amount of time to sit and spend with these patients.”

But the hospital had to come up with some sort of solution. That’s why it started a partnership a year and half ago with Highland Rivers Health, a community behavioral health organization partly funded by the state. In turn, Highland Rivers’ staff will be on site at the hospital to help assess patients and get them connected to other services.

Patti Williams, a behavioral health assessor with Highland, carries a clipboard and flip-phone. When the ER has a patient who might be in the midst of a mental health crisis, Williams gets a call. Instead of patients waiting for hours to get assessed for mental health, Williams and her staff are on site or on-call nearly 24/7.

“Whether it’s in the intensive care unit, on the floor, or the emergency department, I go to [the patients],” she said.

Williams will see if the needs inpatient care at a psychiatric facility, or if they’re OK to go home and then follow up with a counselor and other services.

Since the partnership started, Highland Rivers said the hospital has been able to divert about half the people from the ER and inpatient care to other services – as just one way to address the growing issue.

At Grady, a growing population

On a recent morning, police bring a middle-aged man to the behavioral health wing of Grady’s emergency room.

“We want to see that sometimes because we don’t want to see someone with mental illness taken to jail unnecessarily,” said Michael Claeys, executive director of Grady’s Behavioral Health Services.

The number of patients in Grady’s ER coming in for behavioral health needs has been steadily growing. Back in 2012, he said, the hospital saw about 500 patients a month.

Today, it’s doubled to a 1,000.

“What I’ve seen in the last eight years is just increasing volumes within our emergency room of individuals who’ve got to a breaking point,” he said.

He said the ER has seen patients who wouldn’t have come to the hospital if they had enough preventative care to begin with.

In turn, Grady started ramping up preventative care for behavioral health. It expanded its program with outpatient services so people can follow up with treatment and services – in the hope they don’t end up in the ER again.

Yet, Claeys said the needs in Atlanta are still way greater than the services available, and that Grady can’t be the one shouldering the burden.

“We need everyone to kind of own some of this because Grady can’t really do everything,” Claeys said.” “We’re hanging on by our fingernails every time there’s threats of significant Medicaid cuts because those things will affect our hospital.”

ER doctors advocate for change

On a recent Wednesday at the Georgia State Capitol, Dr. John Rogers, an ER doctor from Macon, walked through the halls in his white coat. It was Physician Advocacy Day.

The ER doctor drove up from Macon to talk about challenges facing the emergency room – including the treatment of mental health patients.

“When I see what happens playing out in the emergency room departments, I am disappointed at our ability to properly care for these patients, and I believe this needs to change,” he said.

Rogers is president-elect of the national American College of Emergency Physicians. He said a priority for the group is better treatment for mental health patients. The Macon doctor said the current experience in an ER is, in some ways, not that much different than what you found in an asylum hundreds of years ago.

“We separate them from their friends and family, we disrobe them and gown them in a fashion that really disrespects their dignity. We put them in a cold and sterile room and we close and lock the door and then we wait,” he said. “There’s not much we do except sedate them and restrain them but we don’t really treat them.”

In a survey conducted by the American College of Emergency Physicians, doctors reported growing wait times for care for mental health patients in an ER. More than 21 percent of physicians said they have patients waiting two to five days for a psychiatric hospital bed.

“We would not accept that for any other disease. And we should not accept this for mental disease. And this needs to change,” Rogers said. “These people deserve our care and our compassion and not our disgust or disdain.”

As head of the organization, Rogers would like to see ER doctors develop treatment protocols with a psychiatrist so that treatment can begin in the ER, and would like to create fellowships in the ER specialized in psychiatric care.

Comedy and hope for Catherine

Catherine Knight, the former attorney, said she could have benefitted from more compassionate care both in the ER and psychiatric hospitals she’s been admitted to.

On a recent Tuesday night, Knight stood before about a dozen other women at a comedy club at the Punchline, a club attached to the Landmark Diner in Buckhead. She held a yellow legal pad, where she’d scribbled her comedy notes in Sharpie.

“I used to practically be agoraphobic which means afraid to leave my house, so this is one of those like ‘jumping out of a plane’ things for an agoraphobic. But there’s something about that adrenaline,” she said. “That’s why I do it. I feel better when I’m when I’m trying to look at the world through kind of a cracked window.”

She talks openly, now about her, mental health challenges – like her in comedy.

“It’s heavy,” she said. “Comedy takes some of that and says ‘Where’s the silver lining? Where’s the common humanity? Where we all can agree that there’s something here that’s funny?’”

She has jokes about her mental health diagnosis, but in this skit, doesn’t talk about her experiences in the ER or hospital. But when she thinks back to them, she said the system needs an overhaul.

“What’s bringing people to the ER?’ and I thought later: everything. That’s the problem,” she said.

She said there’s still so much shame around mental illness and feels like people, including those in the medical community, treat the mind and body completely separately.

“Integrated care would have helped me,” she said. “Treating me like a whole person who needed the basics of warmth and nurturance and attention — and not to feel so strange.”

After several visits to the ER in the last few years, Catherine found her way to a support center in Decatur about a year and half ago. It connected her with counselors who’ve been through a mental health crisis themselves.

She said that’s when her recovery really started. Not in the ER. Or the hospital.

Since then, Catherine herself has trained to become a “certified peer specialist” which allows her to help others who are in crisis or recovery – and to also help them avoid the ER.

Note: For those seeking help with mental health, the Georgia Crisis and Access Line (GCAL) is available at 1-800-715-4225.

Elly Yu is a reporter at WABE, where she covers health, immigration and state politics. Her stories have aired on national outlets including NPR and Marketplace.