Ed Scarborough worked as a sandblaster in the granite industry for 20 years, until his health gave out.

He says he knew that getting into such a line of work was risky, but in Elberton, “there really isn’t much else.”

He was born and raised in Elberton, a historic northeast Georgia town known as the “Granite Capital of the World.” The area’s extensive deposits of the rock — a staple of the building and monument industries — have led to a boom in quarries, manufacturing plants and finishing sheds over the past century.

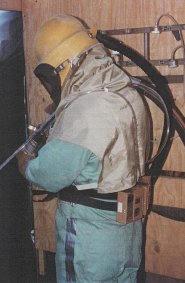

Scarborough worked in the sheds, sandblasting granite headstones to create lettering and designs. He wore air-powered respirators while working, adding, “I never would go in a room and sandblast without it.” But he says his employers did not hold regular safety meetings.

Three years ago, Scarborough says, “I started getting sicker and sicker. I had a problem with breathing. I kept working because I had to live.” During his last months on the job, he says in a gravelly voice, “I was fatigued all the time.” He fell twice at home and sustained two concussions.

His last day of work was in October 2015, he says, when he received a separation notice from his employer, Superior Granite.

Then, after medical tests, Scarborough received a grim diagnosis in August 2016: He had silicosis, a gradual but irreversible lung disease.

Now he is unable to work, and he has the look and bearing of a man decades older than his 53 years.

The past two and a half years have been a financial struggle. Scarborough used to earn about $1,000 a week as a sandblaster, but while he struggled through all the red tape to get benefits, his income was “zero.’’

His wife worked two jobs and the family went on food stamps, and he relied on friends and family for rides to doctor’s appointments. An indigent care program at the Medical College of Georgia in Augusta paid for his specialty care there.

Last month, after initially unsuccessful attempts, Scarborough won his benefits battles with the help of his personal injury lawyer. He received a workers’ compensation settlement and his disability coverage.

Until these financial victories, Scarborough says, “my family and church have put food on the table,” he said. “This almost killed us.”

Tiny particles can do a lot of harm

Silicosis strikes many workers in the construction, sandblasting and mining industries, according to the CDC. It’s caused by exposure to silica or silica dust – essentially sand.

An estimated 2.3 million U.S. workers are estimated to be exposed to respirable crystalline silica through their jobs.

Dr. David Guidot of Emory University School of Medicine says the exposure comes from inhaling very small particles of sand that have aerosolized, or turned into fine dust.

“If enough of this dust is inhaled, you can’t clear it, and immune cells eat these dust particles, causing inflammation that can lead to scarring,’’ which makes it difficult for the person to breathe, he says.

Silicosis can range from a mild case to very severe scarring. The only treatment, Guidot says, “is to remove someone from the insult [the exposure to the dust]. You can’t reverse the silicosis with any medical therapy.’’

Ed Scarborough will never be able to work again, due to the burden of his disease.

His energy is very low, and he constantly suffers from shortness of breath. He coughs frequently. He uses inhalers, which his family doctor sometimes used to give him free when he couldn’t afford the cost. “I stay on antibiotics all the time,” he says.

His weak lungs and ravaged immune system make any new infection perilous. When he recently got the flu, “my body crashed.’’ He had to be airlifted to Augusta for treatment.

Deaths from silicosis are becoming rarer in the United States, and the number of related deaths has dropped to about 100 a year.

But there are no statistics about the prevalence of silicosis, according to the National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH), which is part of the Atlanta-based CDC. NIOSH conducts research and makes recommendations for the prevention of work-related injury and illness.

Most people with silicosis will survive the disease if it is recognized early enough and the exposure is ended, Emory’s Guidot says. He notes that silicosis-related deaths remain common in China and other countries that are becoming more industrialized but still do not have strong occupational safety regulations.

With sandblasting, a worker can inhale large quantities of silica, says Dr. William Davis of Augusta University’s Medical College of Georgia. He sees a few cases of the disease each year. “It’s always an occupational exposure — silica fibers are inhaled into the lungs,’’ he says.

Silicosis can take several years to develop, Davis says.

Physicians typically treat such patients by “giving them medicines to keep their lungs open,” Davis adds. “If the disease progresses to the point that they need oxygen, we can give them oxygen.’’

Is the industry doing enough?

Georgia has an abundance of granite. (Stone Mountain near Atlanta is one highly visible example.) Around Elberton, the “Granite Capital,” there’s a huge belt of it — 35 miles long, 6 miles wide, and 3 miles deep.

The presence of the granite industry can be seen all over Elberton, from billboards and signs to the yards of slab circling the downtown area, and the looming granite pillars and buildings welcoming visitors into town.

More than 100 companies are involved in the business, from quarrying and manufacturing to support service, according to the Elberton Granite Association, which represents about 70 percent of Elberton granite companies. It offers workers’ compensation coverage and OSHA compliance consulting to member companies.

The industry says that over the past 30 years, it has worked to alleviate the impact of silica exposure.

Chris Kubas of the Elberton Granite Association says his organization “is working diligently to address safety as related to silica exposure and to educate our members and their employees on current exposure protection methods.’’

Last month, Scarborough’s workers’ comp claim was settled with the Granite Association out of court. His Social Security disability insurance case, also approved recently, includes back pay for his time spent contesting the initial denial and gives him Medicare eligibility as well.

Scarborough’s last employer, Superior Granite, acknowledged his workers’ comp case, and that of Enrico Fouch, now 48, who worked at Superior Granite from 1999 to 2007.

That was Fouch’s second company, and he worked as a sandblaster in a shed, as Scarborough did.

Toward the end of his tenure, Fouch says, he developed “shortness of breath and fatigue.’’ He started losing weight and wheezing, and developed “a real bad cough.’’

Physicians initially diagnosed him with bronchitis. In the fall of 2007, he called in sick one day. “I could barely breathe,’’ Fouch says. He got a TB test and tested positive for tuberculosis. (People with silicosis are more susceptible to TB, and should be tested regularly, doctors say.)

A pulmonologist soon diagnosed Fouch with silicosis.

Fouch applied for workers’ comp and disability. He says he was initially turned down but later received both. But he also filed a lawsuit against safety equipment manufacturing and supply companies, and eventually received a settlement, the terms of which are confidential.

Defendants in that lawsuit, Pittsburgh-based Mine Safety Appliances Company, Bicknell Supply Company in Elberton, and Miles Supply of Elberton, declined to comment about the Fouch case and other granite worker litigation. But Mike Beri of Bicknell told GHN that the products his company sells are manufactured by “reputable companies. It’s up to the employers to determine how much protection they [the workers] need.”

Fouch had a double lung transplant in 2010, paid for by workers’ comp. He has to take a lot of medications, including anti-rejection drugs. “I still have fatigue,’’ he says. “I can’t breathe in strong smells.”

An attorney for Fouch, Allen Smith, said his Mississippi-based firm represents “several granite cutters” in Elberton.

Silicosis, he says, “is really an unnecessary disease,” adding that OSHA has tried to promulgate new protections for workers.

“You slowly suffocate to death,’’ Smith says. “The sickest people I’ve seen are in the Elberton area.’’

Dr. Jacek Mazurek of NIOSH told GHN that silica exposure “is always bad, and workers should be protected from exposure.’’ He said there are adequate safety measures available.

“We would like to see the control of exposure to silica dust,” Mazurek said.

NIOSH recommends use of a control such as local exhaust ventilation or water spray to reduce concentrations of respirable crystalline silica in the air; limiting workers’ time and access to areas of high concentration; and wearing respirators when working in these areas.

Scarborough says, “I worked in the granite industry for about 20 years and never had a safety meeting.” The Granite Association says two safety meetings per year are mandatory.

Marianne Whitmire, office manager for Superior Granite, says the company conducts regular safety meetings. “We’ve been in business since 1965,’’ she says. “We’ve never had an issue till the last 10 years in sandblasting.”

Whitmire says the company provided the proper safety equipment to sandblasters, and that it was up to the employees to make sure they wore their equipment properly.

“It’s distressing to us that these two good employees [Scarborough and Fouch] have health issues,’’ she says. “We hate it in the worst way.”

Superior Granite no longer does sandblasting on site, but contracts the work out to another company, she adds.

While at least 11 states have NIOSH-funded surveillance programs for work-related respiratory disease, including silicosis, Georgia isn’t among them.

Smoking can make it worse

A new OSHA safety standard will lower the limit on exposure to silica, to 50 micrograms of respirable crystalline silica per cubic meter of air, averaged over an 8-hour day. The level had been 100 micrograms. It will kick in for Elberton granite workers this June.

OSHA issued the rule in 2016, saying it would save an estimated 600 lives and prevent 900 cases of silica-related illnesses annually over all industries.

“Safety has definitely improved,’’ Kubas says. “It can improve more. We want to keep safety in the forefront.‘’

Kubas, meanwhile, declines to comment on the workers’ comp cases of Scarborough or others. He also says the Granite Association is not aware of any current lawsuits involving workers in the Elbert County area.

As part of the Granite Association’s workers’ comp and safety program, all new hires are sent through a screening program, which includes a hearing test, drug screen and chest X-ray, Kubas says.

“Additionally, employees involved in sandblasting operations are required to have follow-up chest X-rays every three years,” Kubas says. “Safety procedures and equipment can dramatically lower, if not eliminate, the chance that silicosis will develop in those employees who work and are exposed to silica.”

He also says that smoking can contribute to workers’ lung problems, even in those who have acceptable levels of silica exposure.

“When we do see silicosis cases, they often are accompanied with the affected person being a smoker,’’ Kubas says.

Former sandblaster Scarborough acknowledges that he has been a smoker. But doctors say that smoking, while it is harmful to the lungs and causes numerous other health problems, is not a cause of silicosis.

Scarborough also has chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, or COPD. While smoking is the leading cause of that disease, exposure to silica dust increases the risk.

Meanwhile, the workers’ comp settlement and future disability checks have given Scarborough’s family a second chance, he says.

“We are finally debt-free and can relax a little,” he says.

Though the results have buoyed Scarborough’s spirits and relieved his money worries, he still gets frustrated about his health problems. He knows he has no prospect of ever really getting well.

“It doesn’t matter if I got $10 million, I’m still going to be sick until the day I die,” he says. “But at least now I can afford to go to the doctor.”

Erica Hensley is a freelance health care journalist based in Athens.