It’s never a good sign when you start urinating blood.

It was 2010, Sara Lewis was 12, and she assumed she had started her period. But what she initially thought was menstrual blood turned out to be something ominous — a sign that her kidneys were failing.

At first, the doctors weren’t sure why the seventh-grader’s kidney function was half what it should have been. Eventually, specialists at Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta diagnosed her with a rare disease that occurs when a person’s immune system destroys blood vessels supplying major organs.

Lewis turned out to have ANCA-associated vasculitis. It’s a condition that starves kidney tissue until the tissue dies, eventually destroying the whole organ.

Tests showed that Lewis was already on that dangerous path when blood showed up in her urine. Toxic wastes were accumulating in her blood, making her tired and lethargic even though she was just heading into her teens.

The doctors told the girl and her family that her kidneys eventually would fail, and that she would need a transplant. She had two options: find a donor on her own or take her chances with the ever-growing national kidney transplant wait list.

More than 5,000 Georgians are currently on that wait list — more than 10 times the number of people in the state waiting for a liver, pancreas, heart or lung combined, according to the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN).

A kidney for transplant can come from either a deceased or a living donor (because a person can live with only one kidney). But whatever the source, there simply are too few kidneys to go around.

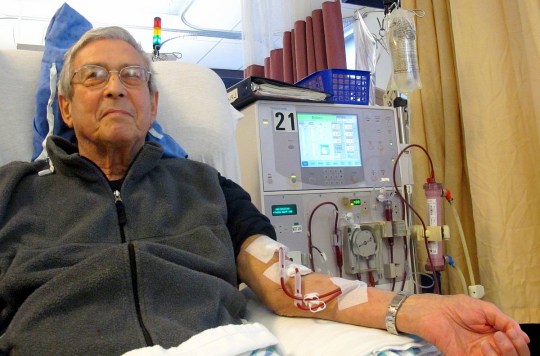

[youtube]https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q0PcogkmuDs[/youtube]And even if there were enough kidneys available, studies have shown that dialysis centers in the state are lax about recommending patients for the lifesaving surgery.

The Southeast has the lowest rates of kidney transplantation by region, and Georgia is at the bottom among those states.

A study published last year in the Journal of the American Medical Association found that just 28 percent of Georgia patients are referred to transplant facilities within the first year of dialysis treatment.

The low number of referrals came even though a transplant is considered the best treatment for most patients with end-stage renal disease. Patients with that disease have kidneys that no longer work well enough to keep them alive, and they need long-term dialysis or a new kidney to survive.

The study, led by Emory University School of Medicine’s Rachel Patzer, also found a big variation in the percentage of referrals among Georgia dialysis facilities – from zero to 75 percent. Patzer, the director of Emory’s Transplant Health Services and Outcomes Research Program, is now trying to hold the area accountable for its low transplant rates.

Changing the rules, reaching more people

When Lewis got the bad news about her kidney condition, she was 12 years old, and transplant surgery seemed a distant prospect. After all, most people whose kidneys shut down are much older. They can barely remember seventh grade.

While she waited, Lewis underwent a series of treatments aimed at protecting her kidneys against attacks from her own immune system.

But five short years after her diagnosis, while her classmates were buying prom dresses and prepping for advanced placement tests, she prepared to receive a new kidney.

Lewis had one of only 524 kidney transplants in the state in 2015. That number is unacceptably low, Patzer said.

Lewis was lucky because her mom, the first member of her family tested as a potential living donor, was a match. And although there were months of filling out paperwork and taking tests, the process was fairly seamless. Lewis got her new kidney at Children’s Healthcare Hospital of Atlanta on May 12, 2015.

Most people in desperate need of a kidney are not so fortunate.

“There are not enough organs to go around,” Patzer said, and Georgia’s kidney transplant rate comes in last place nationally, despite the region’s high prevalence of kidney disease.

Dialysis centers are legally required to educate patients on available treatments, including kidney transplants. If patients are interested in transplantation, the dialysis center should refer them to a transplant center.

But that doesn’t always happen.

The United Network for Organ Sharing, the nonprofit organization that manages organ distribution nationally, restructured its regional maps two years ago. The new rules give younger transplant candidates priority and credit patients’ time spent on dialysis to their wait-list time. The change also gave black patients a better shot at available kidneys.

But Patzer said the new rules don’t address the biggest problem of all: The continuing shortage of kidneys.

One of Patzer’s latest projects is a study called RaDIANT, which stands for Reducing Disparities in Access to Kidney Transplantation. She and her team identified the dialysis centers in Georgia where patients were least likely to be referred to transplant centers.

Then they sent transplant recipients into the centers as peer educators, so they could talk with patients while they were hooked up to the dialysis machines. In Georgia, the intervention doubled the number of referrals from transplant centers.

Kidney disease rife in the South

More education and better treatments for diabetes and hypertension, the leading causes of kidney disease, could keep many people from ever needing a transplant, says Paige Cummings, executive director of the Athens Nurses Clinic. Her organization is a nonprofit that provides free care to uninsured poor people in northeast Georgia.

Keeping one’s own kidneys healthy is not always possible, as in Lewis’ case. But for many people with more common risk factors, it is possible to maintain kidney function with the right measures, and more extreme steps such as long-term dialysis and transplants can be avoided.

Besides the other difficulties associated with transplants — such as a shortage of organs — a transplanted kidney has an “expiration date.” Many patients will have to repeat the procedure years down the road.

Poverty, poor diet and lack of exercise contribute to the South’s disproportionate share of kidney disease. And many people have not had the medical monitoring that would detect disease early.

It’s not uncommon for people to show up at local emergency rooms in acute renal failure with no clue that they have advanced kidney disease.

“All of a sudden they’re told that they need to be on dialysis for life or they’ll die,” Patzer said. “It really should not be at that point that someone learns that they have kidney disease.”

Virginia Campbell got the first hint of her kidney problems the hard way. She experienced a bout of dizziness, suffered a fall at home and was taken to the Morgan Memorial Hospital ER in Madison. EMTs transported her from the small-town hospital to Athens Regional Medical Center, where she was put on emergency dialysis to remove toxins from her blood.

Campbell’s kidney function improved, but she said the episode shocked her into taking action.

“I’m not going to let it happen again,” Campbell said.

Campbell now knows that she has moderate kidney disease, as well as hypertension and diabetes. She is eating a healthier diet, exercising and taking her medications to fend off another crisis.

Sara Lewis, meanwhile, lives in a freshman dormitory at the University of Georgia. Like Campbell, she is taking medications and trying to stay as healthy as possible.

Still, there’s that expiration date on the transplanted kidney. Lewis won’t need another one for 15 or 20 years, but she already has a willing donor for next time. Her sister, Courtney, has signed on.

Leigh Beeson is a graduate student at UGA in the health and medical journalism program. She had a bachelor’s degree in communications and was editor-in-chief of her undergraduate university’s newspaper.