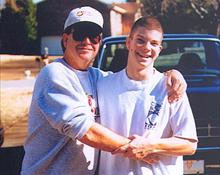

He was a solid student, loved sports, and was active in a youth group.

But Jason Flatt, who lived in suburban Nashville, used his father’s gun to commit suicide at age 16.

Since his 1997 death, his father, Clark Flatt, has helped raise awareness of youth suicide, including among educators.

He created the nonprofit Jason Foundation, which works to prevent teenage suicide. And 10 years after his death, the Jason Flatt Act was passed in Tennessee, requiring educators to complete two hours of youth suicide awareness and prevention training each year in order to be able to be licensed to teach in Tennessee.

The General Assembly recently passed a bill that would make Georgia the 14th state to pass the Jason Flatt Act.

Youth suicide “is a hugely growing problem and is heartbreaking,’’ says state Rep. Katie Dempsey (R-Rome), the legislation’s lead sponsor.

Under the bill, if it is signed by Gov. Nathan Deal, Georgia public school educators would get annual suicide prevention training as part of their in-service training work.

It would not require additional state funds, Dempsey says. “I think it will be very helpful,’’ she says, pointing to statistics on youth suicide.

Within the 10-to-24 age group, suicide is the third leading overall cause of death, according to the CDC.

Georgia’s statistics on suicide and depression (a leading cause of suicide) are near national averages.

In the Georgia 2013 Youth Risk Behavioral Survey, 28 percent of high school students said they had experienced the feeling of hopelessness and sadness for a constant period of two weeks or greater during the past twelve months. That compares with 30 percent nationally.

Among Georgia students, 14.3 percent said they had seriously considered suicide in the past 12 months, versus 17 percent nationwide. And 8.8 percent said they attempted suicide in the past year, compared with 8 percent nationally.

(Among youths 15 to 24 years old, there are about 100 to 200 attempts for every completed suicide.)

Proponents of the bill say the training does not turn teachers into counselors, but helps them recognize warning signs and know how to make referrals for help.

Tim Callahan, a spokesman for the Professional Association of Georgia Education, told GHN, “We didn’t oppose the legislation, knowing as we do that adolescence can be a very difficult time for some of our students. We’ll see how the guidelines come out from the [Georgia Department of Education] for how to achieve the aims of the bill.’’

The state Department of Education says it supported the bill “because it is good for children and does not add any cost for school districts.”

Ellyn Jeager of Mental Health America of Georgia says the state is seeing increasing numbers of young children thinking about killing themselves.

“More of our children at younger and younger ages are considering suicide,’’ Jeager says. “Schools are not equipped to understand or handle what’s going on.’’

The legislation, she says, “is a really good thing. It gives schools help in recognizing the problem and how to deal with it.”