Editor’s note: This story is being reprinted with permission from Georgia State University Magazine.

On a Saturday afternoon in September, dozens of ex-smokers fill a shop tucked into an office park off Highway 316 in Lawrenceville. From the parking lot, a haze is visible inside the shop. On the door, a handwritten sign reads, “We ID! Must be 18 to try or purchase any e-cig products.”

The haze inside, unlike cigarette smoke, clears as quickly as it rises, taking with it the scent of vanilla. It rises again, followed by baked apples, next cherries, then tropical fruit.

The ex-smokers aren’t sneaking a smoke. They’re “vaping” electronic cigarettes — rechargeable pipes and cigarette-shaped devices that vaporize food-flavored liquid nicotine — at the grand opening of Steam Cigs, a “vape” shop and lounge.

No law requires that Steam Cigs be hidden from view in an office park. Nor is the shop forbidden to sell to minors. In fact, e-cigarettes and other “novel nicotine products” enjoy much greater visibility than conventional cigarettes do.

A relatively new product, e-cigarettes fly under the radar and skirt regulations that conventional cigarettes must follow. But that may soon change. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the National Institutes of Health (NIH) have begun to explore regulations of the sale, marketing and consumption of these new products.

Researchers at Georgia State University in Atlanta will help define those future regulations. In the largest grant in university history, the School of Public Health will receive $19 million over five years from the FDA and NIH to establish one of 14 Tobacco Centers of Regulatory Science. The two entities will award up to $273 million over five years to 14 centers selected to conduct scientific research that will inform federal decision-making on tobacco and nicotine regulations.

Michael Eriksen, dean of the School of Public Health, will lead Georgia State’s portion of the research, which will explore the marketing of tobacco and novel nicotine products. The former director of the CDC’s Office on Smoking and Health, Eriksen calls the grant “the culmination of a two-decade effort to put tobacco in the proper regulatory scheme.”

“This grant is one of the first palpable actions FDA has taken to begin the process of regulating tobacco,” he says.

The grant is also among the first to fund research on the virtually uncharted territory of novel nicotine products, a focus of Eriksen’s work, among them e-cigarettes, dissolvable oral nicotine products, even nicotine lollipops.

“We’re looking at what kind of information people need for improved decision-making. But we’ve got to be sure what improved means,” Eriksen says. “Do e-cigarettes get people to quit smoking or are they just a substitute for smoking?”

Since they hit the market in 2004, e-cigarettes have inspired polarizing debates.

“Some people feel that they are just another scam by tobacco companies to keep business. Others feel this is a panacea that could change the epidemic of tobacco use,” Eriksen says. “The two groups are fighting fiercely.”

What’s an e-cigarette?

E-cigarettes resemble conventional cigarettes, cigars or tobacco pipes. They contain a rechargeable battery, an atomizer and a refillable “e-juice” or “e-liquid” that may or may not contain nicotine. Big tobacco companies and small businesses are producing and selling the devices. E-cigarette users are called “vapers,” not “smokers.” A vaper takes a drag from an e-cigarette, the atomizer vaporizes the juice, and the user inhales and exhales the vapor just like smoke.

“It feels like smoking. Having a patch on your arm doesn’t, chewing gum doesn’t. It’s the puffing, the smoke and doing something with your hands,” says Chris Cullen, assistant manager at Steam Cigs.

E-liquids contain propylene glycol or vegetable glycerin, food flavoring and an optional six to 36 milligrams of nicotine per milliliter of juice. Propylene glycol is a thick liquid often used as a carrier of active ingredients in cosmetics and pharmaceuticals, such as cough syrup. The FDA classes it as a food additive that is “generally recognized as safe.” Vegetable glycerin serves similar purposes.

While a cigarette contains about nine milligrams of nicotine, the smoker only gets about one milligram. It’s still unclear how much nicotine e-cigs deliver to the user. A milliliter of juice, however, typically lasts a day for former pack-a-day or more smokers. This can cost as little as a dollar a day.

Heavy smokers usually start vaping with 24-milligram e-juices. Many taper off their nicotine over time. Some ultimately vape only flavored liquid, says Cullen, who smoked for 35 years. He hasn’t had a tobacco cigarette in 15 months, and he hasn’t had nicotine in nearly two months.

“I was on 24 milligrams for six months, then 18, then 12, then six and now zero since about seven weeks ago,” he says. “So I’m just puffing nice, fruity flavors.”

Are users getting burned?

Public health experts don’t have a fraction of the information on e-cigarettes that they have on conventional cigarettes. It took 15 years of research to determine tobacco cigarettes cause lung cancer. Other ills of smoking have continued to pile up in the 50 years since. It would take decades for researchers to compare the long-term effects of vaping and second-hand vaping to smoking.

But Eriksen warns against that.

“We can’t wait until we have a body count,” he says.

But even e-cigarettes’ toughest opponents concede they can’t be as harmful as cigarettes. They don’t contain tobacco and they don’t burn.

“They produce fewer toxins. Exactly what they produce and how much is still getting worked out,” says Stanton Glantz, a staunch opponent of e-cigarettes and a colleague of Eriksen who also won a grant to set up a Tobacco Center of Regulatory Science at the University of California-San Francisco.

“Analog” cigarettes, as vapers call tobacco cigarettes, contain some 600 ingredients to e-cigarettes’ three. When burned, cigarettes produce 4,000 chemicals, 50 of which are known carcinogens or poisons.

What e-cigs and “analogs” have in common is nicotine itself, a stimulant often compared to caffeine but not entirely benign. Approved smoking cessation products, such as patches and gum, contain nicotine as well, but anti-vapers argue the FDA controls those doses. While the FDA doesn’t regulate e-juices, some independent studies have confirmed the juices do typically contain what they say they do.

Weighing the bad and the good

Because big tobacco companies have an interest in e-cigs, some opponents insist they cannot be trusted.

“They say we can’t work with them. They’ve manipulated us before and been found guilty of fraud,” Eriksen says.

Opponents suspect these products will only deceive users into thinking they reduce harm, just as filter cigarettes and light cigarettes once did.

Proponents tout the product’s potential to reduce harm.

“It’s best to quit smoking completely, but 97 percent of people who try are unsuccessful,” says Michael Siegel, a physician and a professor in Boston University’s School of Public Health.

Siegel, a friend and colleague of Eriksen’s, believes e-cigarettes are promising for those who would otherwise never be able to quit smoking.

“Everything that’s come before this focuses only on the pharmacological aspect of the addiction. This is the first product that also focuses on the behavioral aspect,” Siegel says. “The hand motion, the throat hit, the holding of the cigarette, even some of the social aspects. You can smoke with others in a group.”

Siegel’s published research cites the social aspects of vaping as a strength over clinical nicotine replacement therapies. Vapers often become hobbyists and collectors of paraphernalia, which provides them an identity and a supportive community.

It’s not unfounded that e-cigarettes can help smokers quit. Besides success stories like Cullen’s in virtually every online forum, studies — though still small — document e-cigarettes’ ability to satisfy cigarette cravings and aid in smoking cessation. In a recent study in “Substance Abuse: Research and Treatment,” 42 percent of smokers substituted all smoking with vaping within one month when they used juices containing 15 milligrams of nicotine or more.

Opponents argue, however, that these smokers might have kicked the habit completely had it not been for e-cigs. They say some smokers only use e-cigarettes as a means of cutting back on conventional cigarettes, which Glantz says isn’t enough.

“If you’re smoking any cigarettes, you’re pretty much suffering the full cardiovascular risk,” he says.

Research also shows many vapers are still smoking. A recent study in “Nicotine and Tobacco Research” found that significantly more current smokers than ex-smokers use e-cigarettes. However, while e-cigarette opponents also argue the products will lure those who’ve never smoked, this study and others in the same journal suggest otherwise.

Eriksen believes the truth about e-cigarettes lies somewhere in the middle, between strong support and fervent opposition.

“That’s why we’re doing this work,” Eriksen says. “Neither of them is right.”

Until more facts surface, leaders in health promotion, such as the American Lung Association and Mayo Clinic, warn consumers to steer clear of e-cigarettes.

Whether e-cigarettes will have long-term effects on users, anti-vapers fear that vaping in places where smoking is prohibited will “renormalize” the act of smoking and undo years of public health efforts to make smoking socially unacceptable.

Marketing restrictions and increasing public smoking bans have “denormalized” smoking for the last 30 years.

“We’ve made all this progress,” Eriksen says, “But if smoking becomes renormalized through e-cigarettes, that’s a major public health concern. It could become more socially acceptable and kids would see.”

Return of the ‘cigarette girl’

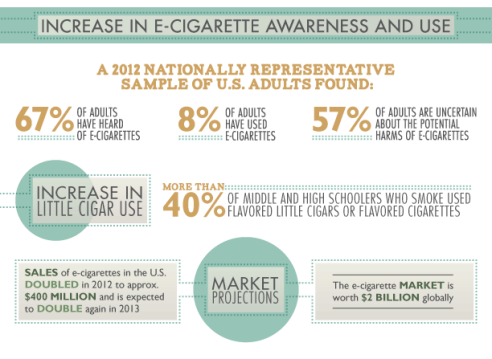

Kids can already see e-cigarettes at eye level in the convenience store, at mall kiosks and between the fingers of sex symbols on TV. The proportion of middle and high school students who had ever tried an e-cigarette doubled last year, from just over 3 percent to nearly 7 percent, according to the CDC.

TV personality Jenny McCarthy, a former Playboy centerfold and outspoken anti-vaccine activist, is the spokeswoman for Blu e-cigarettes.

In a television commercial, McCarthy vapes in a bar. She says she loves being single, but she doesn’t love kisses that taste like ashtrays. During a montage of shots of McCarthy flirting with the man next to her, she counts the ways e-cigs beat conventional ones. She can use them anywhere without any guilt. She doesn’t have to go out in the cold. She doesn’t smell bad or get dirty looks. Rubbing the arm of the man next to her, she says she won’t scare that special someone away.

E-cigarettes make it easier for her to pick up a man in a bar.

“Are you buying the e-cigarette or are you buying Jenny McCarthy or does one come with the other?” Eriksen asks.

The only thing McCarthy can’t say in the commercial is that e-cigarettes helped her quit smoking. That would be a medical claim.

Not surprisingly, whether e-cigs should be advertised at all depends on whom you ask. Opponents feel the new products should be treated just like cigarettes.

“I don’t think they should be used indoors. And all the same marketing restrictions that apply to cigarettes should apply to e-cigarettes,” Glantz says.

Others propose banning any flavors other than cigarette-flavored or banning the product all together.

But proponents don’t want to limit the reach and desirability of a product they feel has the potential to help smokers quit.

“Anti-tobacco organizations think the flavoring attracts kids, but adults like flavors, too,” says Matt Wellman, owner of Steam Cigs. “If we have to make them taste like tobacco, that would just drive people back to cigarettes.”

Wellman supports a federal ban on the sale of e-cigarettes to minors.

Proponents feel the products should be advertised for what they really are: not a way to smoke in the non-smoking section, but a way to quit smoking everywhere.

“It’s obvious they shouldn’t be marketed to anyone under 18, but you have a product that could help the public and you’re not allowed to tell them what it does,” Siegel says.

He says if e-cigarettes were marketed as smoking cessation devices, they would lose all potential appeal to children.

Smoke-free support

Vapers in the lounge at Steam Cigs would also hate to see e-cigarettes hidden from the people who need them. Ryan Cook is somewhat of an e-cig evangelist. The 35-year-old started vaping 20 months ago. He immediately kicked the smoking habit he had picked up at age 16. Now he shares his story at vape conventions, trade shows, in online communities and anywhere else he can. He coaches people who are trying to switch to e-cigs in order to help them avoid relapse.

“Of course there was a slight urge to smoke, but you have to be ready to put it down in order to make it happen,” Cook says.

Cook compares the patrons at Steam Cigs to the members of a 12-step program.

“It’s part of the recovery process,” he says “It’s harder to quit smoking when everybody around you smokes. Here everyone is an ex-smoker.”

The patrons exchange ideas about vaping paraphernalia and share stories about how long they’ve been tobacco-free. They recount regaining their sense of taste, being able to climb stairs without getting winded and losing the smoker’s cough.

Cook wears his e-cigarette on a lanyard around his neck.

“I always wear one because it’s associated with quitting smoking,” Cook says. “It connects me to converts that I can coach off of smoking. It’s about converting smokers to non-smokers, and I’m very passionate about it.”

Like Cook, Georgia State’s Erickson would recommend an e-cigarette to an individual trying to quit. He suggested them to his father-in-law. But as a tobacco expert, he doesn’t have enough information yet to recommend e-cigarettes to the public as a safe alternative to smoking.

“Getting nicotine without the smoke is good,” Eriksen says, “but is it good enough? That’s what we need to find out.”

Here’s a link to the original GSU Magazine article

Sonya Collins is an Atlanta-based independent journalist who covers health, health policy and scientific research. She is a regular contributor to WebMD Magazine, Pharmacy Today, Yale Medicine and Georgia Health News.