Betting on Reno(Editor’s Note: This is the fifth in a series of articles on the Athens uninsured initiative, produced by graduate students in the Health and Medical Journalism Program at the University of Georgia. Visit the previous articles by clicking on the red button to the left.)

[youtube width=”620px”]https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZrhreS1ytfI[/youtube]

For many small businesses in Reno, Nev., the Access to Healthcare Network (AHN) has been a godsend.

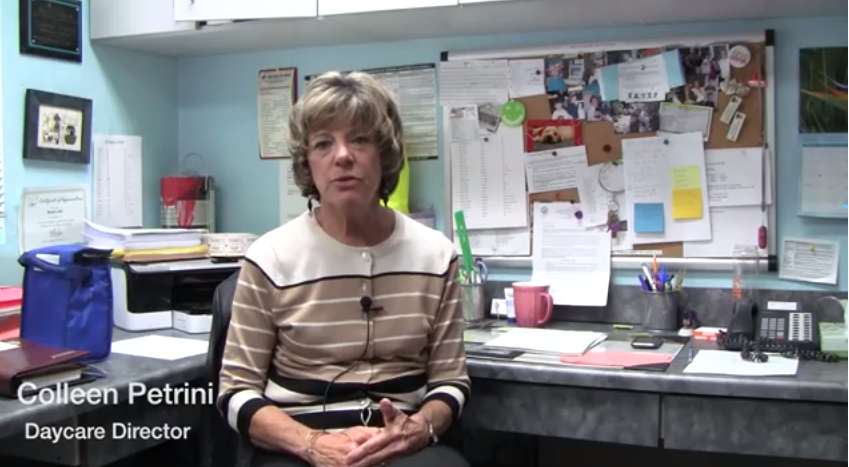

“As an employer in this day and age, I have found it’s not so much the hourly wage that you offer people anymore,” says Colleen Petrini, director of Noah’s Ark Child Care Center. “It’s the benefits.” But benefits cost money.

Her center used to offer health insurance to all employees. But when the economy went sour in 2008, Petrini says, she could no longer afford the monthly payment she had been making for each employee’s coverage. And it was harder for the workers to kick in the monthly paycheck deduction for individual insurance.

Fortunately she heard about AHN, an alternative to health insurance. It’s a nonprofit medical discount plan based in Reno, and it began in 2007 with the mission of increasing access to primary and specialty health care for underinsured and uninsured residents of Nevada. It works on a “shared responsibility” model, in which partnerships between hospitals, doctors, businesses and individuals ensure that Nevadans can get and help pay for low-cost health care.

After learning more about what AHN had to offer, Petrini dropped her insurance plan and signed up. The center and its teachers split the monthly fee.

Here in Georgia, the Athens Health Network plans to bring a similar discount plan to the Clarke County area next year.

Small businesses have typically listed the cost of health insurance as their No. 1 concern in surveys by the National Federation of Independent Business.

That cost has made coverage unaffordable for many small firms. A 2008 study found that employees of small firms were twice as likely as employees of large firms to be uninsured. Small business employees had a 25.1 percent unemployment rate nationally, whereas the rate of uninsured large business employees is 13.6 percent.

Offering insurance is important to recruiting and retaining good employees. “Many people would not sign onto a job if they knew there would not be health insurance benefits,” said Josh Cole, who helps network members in Nevada’s Washoe County, where Reno is located, obtain the care they need. “So that [lack of health coverage] automatically takes away a big talent pool from these small businesses that are otherwise doing a great job.”

Petrini’s day care is not the only Reno business that has suffered in recent years. The city’s gambling industry, which has been its economic mainstay for generations, has been hit hard by increasing competition.

With American Indian casinos on the rise across the nation, and many more states legalizing gambling within their borders, such traditional gaming-and-entertainment destinations as Las Vegas, Reno and Atlantic City, N.J., have taken a hit.

Reno has suffered particularly, because it’s near the California line, and most of its business historically came from Californians who crossed over to gamble. Now those people often stay in the Golden State and play at Indian casinos rather than making the trip to Nevada. Reno’s gambling revenues have fallen by a third since reaching a peak in 2000.

The city also took a beating from the housing market crash that precipitated the Great Recession. Between 2007 and 2010, the median home value in Reno declined 37.4 percent, the 13th-biggest drop in metro areas of the country.

During this time, the Access to Healthcare Network was growing to meet the needs of a state that was economically flailing. The discount plan expanded in 2009 to serve residents of rural Nevada through funding from the federal stimulus package. It expanded to Clark County, where Las Vegas is located, in the summer of 2010.

Members of the network pay a monthly fee that gives them access to a large number of specialists, clinics and hospitals. The members pay cash – at deep discounts – for the care they receive.

Since its inception in 2007, AHN has served more than 11,000 Nevada residents.

A big question mark

AHN has had a remarkable rise so far. But now that full implementation of the Affordable Care Act, or Obamacare, is moving ahead, the future of the Nevada network is unclear.

Under the law, small businesses with more than 50 full-time equivalent (FTE) employees will be fined if they fail to provide affordable health coverage for their employees. If employers with 51 or more FTE employees fail to provide this coverage, they will face an annual fine of $2,000 per employee (excluding the first 30).

The even smaller businesses, those with fewer than 50 FTE employees, will not suffer penalties for failing to provide health benefits. Some businesses with less than 25 FTE employees will qualify for tax subsidies to make coverage more affordable.

Some companies, once they are required to have insurance or be fined, will drop AHN and use the money they would pay into it to buy the coverage instead.

“The ACA [Affordable Care Act] will result in some of our clients going away,” said Cole, the AHN staffer.

But the Affordable Care Act will not be the solution for everyone. The insurance options available on the exchanges coming in January may be more expensive than the $40 per month AHN membership fee added to the fine for not providing coverage.

Also, people in the area without documentation of legal U.S. residency will keep turning to the Access to Healthcare Network, because they can enroll without providing a Social Security number.

Melissa Nixon, human resources director of Great Basin Community Food Coop in Reno, said her business will stay with AHN even after the Affordable Care Act is fully implemented in 2014.

Because Great Basin has fewer than 20 full-time equivalent employees, the nonprofit is not required to offer health insurance to workers.

Even if the government subsidies would help the food co-op provide standard health insurance, Nixon predicts that her organization will stick with the locally grown Access to Healthcare Network instead of switching to conventional insurance.

Through AHN, she and the other employees of the co-op can depend on getting preventive and emergency care from a network of people who are invested in the well-being of community members.

“They have really great customer service,” said Nixon. “The care coordinators have relationships with our employees and are able to best match their medical program with their needs.”

Jodi Murphy is a graduate student at the University of Georgia Grady College of Journalism and Mass Communication, pursuing a concentration in Health and Medical Journalism. She is particularly interested in environmental and global health, as well as women’s issues.