When Maya put paint chips in her mouth, her mother instantly knew the danger.

Sarah Tuck recognized that their Savannah rental home, built 100 years ago, could contain lead. So she got Maya tested through a doctor’s office.

The reading for Maya when she was about a year old was a disturbing 18 micrograms of lead per deciliter of blood.

The CDC says there’s no safe level of lead, but a reading of more than 10 is perilously high, and prompts a state environmental investigation of the home.

Lead, a neurotoxin, can harm children significantly. Researchers have found that even at low levels, lead can damage a child’s brain, lowering intelligence and damaging the ability to control their behavior and attention. At higher levels, lead can affect growth, and it can replace iron in the blood, leading to anemia and fatigue.

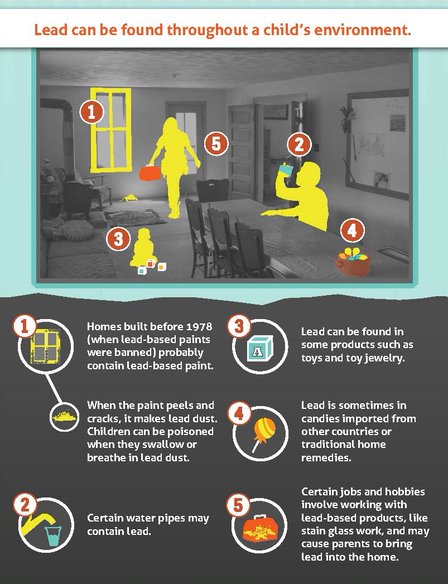

Lead is a naturally occurring element that has historically been used in manufacturing, though much of that use has been discontinued. Children can be exposed to it through lead paint, tainted water or soil, and certain toys and other objects.

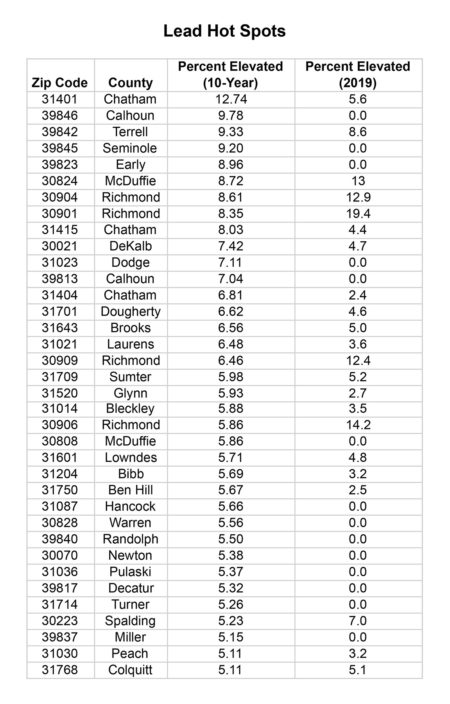

An analysis of state data by Georgia Health News and the AJC has determined which ZIP Codes have the highest percentages of young children testing high (5 micrograms per deciliter and above) on lead levels in their blood over the past 10 years.

This ZIP Code data, obtained by the Georgia News Lab and GHN through an open records request, has not been publicly available before.

Sarah Tuck’s ZIP Code in Chatham County had the state’s highest percentage of kids tested with elevated lead levels over the 10-year period.

In the 31401 area, 12 percent of the children tested had high levels over that time. The state average is about 2 percent.

In fact, Chatham County has three of the top 20 ZIP Codes. In each of those, more than 6 percent of kids tested were found to have troublingly high readings.

“There is a ton of lead paint in this town,’’ says Dr. Ben Spitalnick, a Savannah pediatrician. “The paint flakes and it becomes airborne.’’

“High-risk kids in Savannah live in high-risk ZIP Codes,’’ he adds.

The soil in Savannah neighborhoods contains high amounts of lead and other heavy metals, says Maria Wargovich, regional Healthy Homes coordinator for the public health district.

That contamination stems from past industries such as smelters and lead paint manufacturers, and demolitions of older housing stock, Wargovich adds. “The lead from leaded gasoline is still found in the soil along highways and roads in and around Savannah.’’

Hidden in old houses

The county’s investigation of the Tuck home found that it was filled with lead paint, and that the soil outside also contained high levels.

“There were signs of paint deterioration on both the interior and exterior of the house,’’ said a letter to the property owner, obtained by Georgia Health News. “The lead wipes and soil samples revealed several areas of hazardous levels of lead on the interior of the house.’’

Savannah, Georgia’s oldest city, has the oldest housing in the state, says Chris Rustin, administrator of Chatham’s Health Department. The fact that it has ZIP Codes with high rates of lead problems, he said, “doesn’t surprise me.’’

“This is still an ongoing issue,’’ says Rustin, who has made lead a priority health issue in the Savannah area.

Another area with an obvious lead problem is Richmond County, home of Augusta. It also has three of the top 20 ZIP Codes with high rates of kids with lead problems. Each ZIP Code in 2019 had at least 12 percent of children tested having blood lead levels at 5 micrograms per deciliter or higher, state data show.

Those areas feature high rates of poverty and older housing, says Dr. Stephen Goggans, the district public health director. The worst ZIP Code for lead in Richmond County is the same one where the Augusta National Golf Club, home of the Masters, is located.

“We do see a lot of kids with ADHD,’’ says Dr. Donna Moore, a pediatrician at Augusta University Health.

Studies have found lead exposure is associated with children developing attention deficit hyperactivity disorder.

A federal HUD grant aims to reduce these Augusta numbers. The county will benefit from $3.3 million in funding to remediate 120 properties. The work has not yet started, state officials say.

“It will pay dividends in the future,’’ Goggans says. “It will reduce in a meaningful way these risky properties.’’

The grant is welcome news. That’s because CDC funding for Georgia’s statewide lead prevention program has dropped in the last two years — from $600,000 to $534,000.

(To view the full ZIP Code list, click here.)

Sources of lead

Surprisingly, just one metro Atlanta county landed in the top 20 hot spots for lead. That’s DeKalb County, specifically ZIP Code 30021, where Clarkston is located, It’s an area with a high number of refugees and immigrants.

Ryan Cira, director of environmental health for DeKalb County, says the area’s housing stock generally dates to after 1978, when lead-based paint was banned. “With this population, it isn’t the housing,’’ Cira says. “There are refugees coming in already poisoned.’’

Products containing lead could range from spices and foods to medicines and makeup, says Dr. Jennifer Sample, a Kansas City pediatrician and an expert on lead’s harm to children.

The crisis in Flint, Mich. – where lead-contaminated water poisoned a high number of children beginning in 2014 — raised awareness of the toxin in many parents’ minds.

“People started talking about lead,’’ says Dr. Sample. But many have focused on tainted water rather than other sources of contamination, both inside and outside the home.

Two pediatric offices in Augusta cited high levels of lead in the blood of kids who had at least one parent working in a battery plant. These plants regularly use lead in the manufacturing process.

One child tested at 57, said Cheryl Weaver, a medical assistant at Christ Community Health, an Augusta federally qualified health center.

An Augusta battery plant was cited by OSHA last year for exposing employees to lead, unguarded machinery, and other safety hazards.

“Elevated lead levels can cause debilitating and permanent health issues,” said OSHA Atlanta-East Area Director William Fulcher in a statement on the penalties at U.S. Battery Manufacturing. “OSHA’s lead standard requires employers to minimize workers’ exposure by using measures including engineering controls, safe work practices, and providing protective clothing and equipment.”

Company officials could not be reached for comment on the OSHA action.

Some doctors surprised

In rural ZIP Codes, just a few kids with high lead levels can make an area a hot spot because of the lower overall number of children tested.

Still, some physicians interviewed by GHN indicated surprise at the rate of child lead poisoning in their communities.

Dr. Ajay Gehlot, CEO of CareConnect Health, which runs an Eastman clinic, says that he didn’t know about the high rates there until a reporter brought it to his attention.

“From January 2018 to May 2019, seven of 24 kids tested had 3 or higher,’’ Gehlot said, after checking the clinic’s figures. “Two of them were strongly high. I didn’t know about it. It was an eye-opener for me.’’

Other rural counties also have “red zone’’ status, including two ZIP Codes in Calhoun County in southwest Georgia, though no kids tested high there last year.

Nearby Terrell County had recent child cases investigated by public health. The cause of the poisonings was “deteriorated lead-based paint and/or lead dust,’’ state officials say.

Another ZIP Code with high rates of elevated lead levels in kids over the 10-year period is in rural Ashburn, in Turner County in South Georgia.

That’s where Montie Poteet believes her young son Austin found flecks of old paint around their rental house and porch. The chips stuck to his tiny fingers, which he often sucked on, as most babies do.

When a pediatrician tested Austin’s blood during his regular check-up at 16 months of age, the lead level was 17.

Montie told WebMD and GHN that she thinks the paint in the house — which was built in 1904 — may have had lead in it, and it may have permanently damaged Austin’s brain.

She says when they signed the lease, they never received a warning that there could be lead in the house. Federal law requires anyone who is renting or selling a home built before 1978 to notify future occupants that there could be a lead threat.

In April 2017, Austin, then almost 3, was officially diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder. The family moved as soon as they were able to get the money for a new apartment.

Austin, now 6, is in a special education class in neighboring Irwin County. “He loves reading; he’s very smart,’’ Montie Poteet says.

His lead level has dropped to under 5.

Austin, she says, “still has behavior issues. He still is having tantrums.’’

More testing needed

Many children don’t get tested for lead despite pediatric guidelines, experts say.

The Medicaid program requires this screening. According to statistics from the state, the health plans that serve Medicaid children report about 80 percent of the kids being tested.

State data don’t indicate recent testing rates of PeachCare kids.

Nationally, “we don’t know how many children are lead poisoned,” says Dr. Sample. “We need more testing.”

And this year, with COVID-19 raging across the country, many parents are not bringing their children into doctor offices for well-child check-ups.

The American Academy of Pediatrics says a significant drop in well-child visits “has resulted in delays in vaccinations, delays in appropriate screenings and referrals and delays in anticipatory guidance to assure optimal health.’’

Dr. Hugo Scornik, a Conyers pediatrician and president of the Georgia chapter of the AAP, said pediatricians “are reporting that visits for preventive care and immunizations are down from their normal levels. We saw some rebound in the late summer, but parents still aren’t bringing their children in for preventive care as much as they usually would.’’

Parents’ hesitation about visiting doctors’ offices will lower the number of kids checked for lead problems, experts say.

“There will be a lot fewer kids tested,’’ Sample says.

Lead levels detected in recent years are far lower than in the era of lead paint and leaded gasoline, experts say.

Still, the number of Georgia children testing at 10 and above in 2019 was the highest in seven years.

A recently added electronic alert in the state immunization registry for physicians, Rustin says, should increase the testing rates for kids, especially in ZIP codes that are potential hot spots.

The risk of renting

When a child tests at between 5 and 9 micrograms per deciliter, the public health department sends a letter to the family, indicating the presence of a problem and giving education.

A child testing at 10 or above triggers a public health inspection of the home. If it’s rental property, a copy of the inspection and the letter goes to the landlord as well as the family.

If the child’s level is 15 or above, the state can take action to reduce the hazard.

Living in a rental property is a risk factor, because these locations are more likely to have lead than owner-occupied dwellings, Rustin says. And in Savannah and elsewhere in Chatham County, he adds, more people rent the homes where they live than own them.

The potential cleanup, though, can be elusive. Many landlords don’t want to spend the thousands of dollars it can take to fix the residence, health officials say. And tenants may be evicted if they complain, attorneys say.

“Tenants need to figure out another place to live,’’ adds Lisa Krisher of the Georgia Legal Services Program. “They don’t want an eviction on their record.’’

Georgia is one of very few states to not require a warranty of habitability for rental property.

“Lead paint remediation is expensive,’’ notes Susan Reif of the Legal Services Program. A landlord often “will just get rid of that person or family.’’

Action can save a child’s health

A high lead reading does not necessarily result in permanent damage, Sample says.

Many children, if removed from the source of lead, ”are going to be fine in the end’’ with the right interventions and brain enrichment, she says.

When told about Maya’s lead level, Sarah Tuck immediately got to work on the house. The family used lead-free paint to cover the walls.

But she says the owner of the home objected, saying it ruined the appearance. The family soon moved out, first to Asheville, N.C., and then to Washington state, where Sarah works as a doula, a provider of help and support for pregnant women and those with newborns.

Maya’s blood lead level is now less than 2.

Sarah credits that improvement in her daughter’s condition to healthy eating habits, supplements such as turmeric, and the fact that Maya has been breastfed for a long period of time.

“She’s very sharp for her age,’’ Sarah says. Maya may “have a little ADHD,’’ she says, but adds that she herself has it, too. ADHD can run in families.

Tuck has advice for parents: “There’s so much toxicity in the environment. We need to be aware of what our children are exposed to.’’

The AJC’s John Perry and the Georgia News Lab’s David Armstrong contributed to this article.