By Madeline Laguaite

When Julie Burton was growing up, she had a hard time communicating with the people and the world around her.

Being born profoundly deaf posed many challenges for the young Burton. But life changed for her when she started school at the Alabama School for the Deaf (ASD) and became immersed in the deaf world. She’s now an American sign language teacher at the Georgia School for the Deaf, and is one of about 48 million deaf and hard-of-hearing individuals living in the United States.

The coronavirus pandemic, however, has posed challenges for the deaf community and reintroduced some barriers to communication that Burton faced in her childhood.

For one thing, facial expressions are an essential part of American sign language, or ASL. And since masks worn to deter COVID-19 typically cover most of the face, they can block many of these expressions.

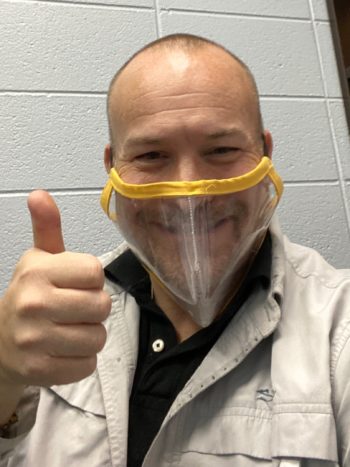

“Having our faces covered has caused distress and frustration for me,” says Greg Reese, a deaf high school English teacher born and raised in Atlanta. “There is an option of a clear see-through mask, but it is not easily available in sufficient numbers.”

The difficulty of not being able to see faces clearly also affects communication between deaf individuals and interpreters.

At a doctor’s appointment, Reese says, he was frustrated at being unable to see his interpreter’s facial expressions clearly. From the interpreter’s standpoint, it was also more difficult for her to translate because she wasn’t able to read Reese’s face clearly.

“Facial expressions color our dialogue the same way the tone of voice colors daily speech,” Reese says.

Burton has faced the same struggle of having to wear a mask. She’s unable to speak with people who can hear — nor can she read their lips — so she now relies on her smartphone to communicate with them.

Brian Leffler, an ASL professor at the University of Georgia, notes that it’s a real, distinct language but differs significantly from a spoken language. “When you think about ASL, we’re not verbal, obviously. We have different grammar and we have different facial expressions. It’s not necessarily for an emotional value to have your expressions, but your expressions represent grammar — it’s a sophisticated form of communication.”

Jimmy Peterson, executive director of the Georgia Center of the Deaf and Hard of Hearing, says he encourages more businesses and people in the community to wear clear masks, because many deaf or hard-of-hearing people don’t know ASL and instead rely on lip reading.

The social scene takes a hit

Reese says that he believes the pandemic has had a worse impact on the deaf community than on people who can hear.

“We deaf are very sociable,” Reese says. “We often meet and visit each other. We often hold events and rallies. We cherish being able to sign and be understood by each other. We crave in-person interactions. While I cannot speak for everyone, the pandemic hit me significantly by physically isolating me from the deaf community.”

Burton is part of a local deaf organization in Cave Spring, in northwest Georgia, where the school for the deaf is located. The group normally hosts deaf events every month, and she always has enjoyed this kind of socializing. But COVID has led to cancellation of the gatherings.

“It’s really tough,” Burton says. “I have missed socializing with deaf people so much.”

And during the pandemic, interpreters aren’t always available like they used to be. “I think it’s because so many people are teleworking and now, I’m having to wait for an interpreter to get on the line in order to place my call, which isn’t something I’m used to pre-COVID,” Leffler says.

But there are some positives.

“I get to see my daughter grow up,” Reese says. “I used to hold down two or more jobs, so I was not home much. It is nice to be able to spend more time with my family.”

Teaching has to be done differently

Educators across the nation have adjusted their teaching styles during the COVID-19 pandemic, and Reese, Burton and Leffler have all felt the challenges of online learning.

“This year, I should have been teaching in a classroom with my students present,” Reese says. “I should be able to provide large-group, small-group, and one-on-one instruction. Ever since the pandemic hit, I have been at home doing differentiated distance learning with my students.”

Leffler says using technology like Zoom presents its own challenges.

“It’s kind of hard to gauge purposes,” Leffler said. “You’re on a two-dimensional screen, trying to study a three-dimensional language, and you don’t have that space.”

Because facial expressions affect a message in terms of tone and meaning, it’s a critical lesson that Leffler teaches.

“Pre-COVID, in the classroom, you have that turn-taking . . . I expect them to respond and not have a blank expression on their face,” Leffler says. “Now with COVID, [for] those who are not coming to campus, we’re experiencing some challenges trying to do this in a two-dimensional space.”

Dealing with common myths

The COVID-19 pandemic has shed some light on the obstacles the deaf community faces on a daily basis.

Misconceptions include the notions that deaf individuals can’t drive, that they all read Braille and are all expert lip-readers. All these misconceptions can be frustrating.

“[People think] we do not know what is going on around us, for we cannot hear and thus are not aware of what is happening,” Reese says. “[They think] we like being screamed at, because apparently sheer volume does help us hear [or that] we enjoy seeing people fake-signing or signing gibberish.”

The fact is, not all deaf people can read lips. Peterson, for example, says he can’t read lips very well.

Leffler said a big irritant for him is when people ask if he can read their lips.

“Sometimes for cultural negotiation, or like trying to bridge that cultural gap, I may mouth back something very simple and they’re like, ‘Oh, I can’t understand. I don’t lip-read,’ and I’m like, ‘I don’t either. I don’t know why you’re asking me to lip read,’ ” Leffler says.

Reese says hearing people can be better allies to people in the deaf community by being more sensitive and not being afraid to communicate, like writing notes back and forth.

“At the same time, if a deaf person says ‘no’ to an offer of assistance, accept it and move on,” Reese says. “Don’t automatically assume the person you are talking to is rude because they don’t respond. They just might be deaf. This happens to me a lot.”

Praise for Georgia

One of the most critical issues that deaf and hard-of-hearing individuals have faced lately is a lack of access to information about COVID-19.

The National Association of the Deaf (NAD) and five deaf Americans sued the White House on Aug. 3, arguing that the Trump administration violated federal law by not including an ASL interpreter during televised broadcasts on the COVID-19 pandemic.

The lawsuit claims that the White House has violated Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act, which protects people with disabilities from discrimination. The White House referred inquiries to the Justice Department, which declined to comment.

“When the Trump administration doesn’t provide adequate access to important information, others, including states, or even local governments also feel as if it isn’t important to provide it,” Reese says. “Deaf people feel they are ignored.”

“It’s not even like a Democrat or Republican situation,” Leffler said. “It’s just a constitutional right to have access, simple as that, [and it] doesn’t need to be any more complicated. And D.C. has no excuse — They have way more certified deaf individuals than anybody else.”

There’s a “stark contrast” in terms of accessibility during the pandemic between Georgia and Washington, D.C., Leffler says.

“When I see Gov. Brian Kemp, I see they actually have a deaf interpreter there,” Leffler says. “I’m very impressed with Georgia as a state. I think we fare much better than what the White House does, embarrassingly so.”

Reese commends deaf interpreter David Cowan, who interprets at Kemp’s COVID-19 press conferences. A video of Cowan went viral last year after a video of him interpreting Beyonce’s “Get Me Bodied” at Atlanta Pride was shared on social media.

Hope for change

ASL classes have become more common at public schools and universities in the past few years, and these classes allow more people to become aware of ASL and deaf culture, Peterson says.

Burton says she wishes more people knew ASL.

“If there is one thing I have observed, it is this: Sign language unites all deaf people,” Reese says. “Disability does not equate to a lesser humanity. Asking for communication in a different way than the spoken word does not negate the importance of said communication.”

Madeline Laguaite is a freelance journalist and a health and medical journalism graduate student at the University of Georgia. She is particularly interested in LGBTQ health and public health. She has a public/professional Twitter at @MLaguaite and a portfolio at www.madelinelaguaite.com.