PART SIX OF SPECIAL REPORT

By Andy Miller and Erica Hensley

Andy Miller is editor and CEO of Georgia Health News, and Erica Hensley is a freelance health care journalist based in Athens. This investigation was done in collaboration with WebMD, and was supported by a grant from The Arthur M. Blank Family Foundation.

Principal Keisha Sims sent an urgent email request in April.

Tests had found that water at Margaret Harris Comprehensive School contained high levels of lead. The school was “in desperate need of additional water,’’ Sims wrote to a DeKalb County School District official.

“We are a school that serves students with severe disabilities, and we need access to water for diapering, G-tube feeding, suctioning and severe medical needs,’’ she wrote, requesting that district officials send bottled water. Georgia Health News obtained the email under the Georgia Open Records Act.

Sims received bottled water after the school found a high level of lead in several areas, including in a drinking fountain. The metro Atlanta county’s school system is one of the few in Georgia to test drinking water at every source in every building, which is what lead experts recommend.

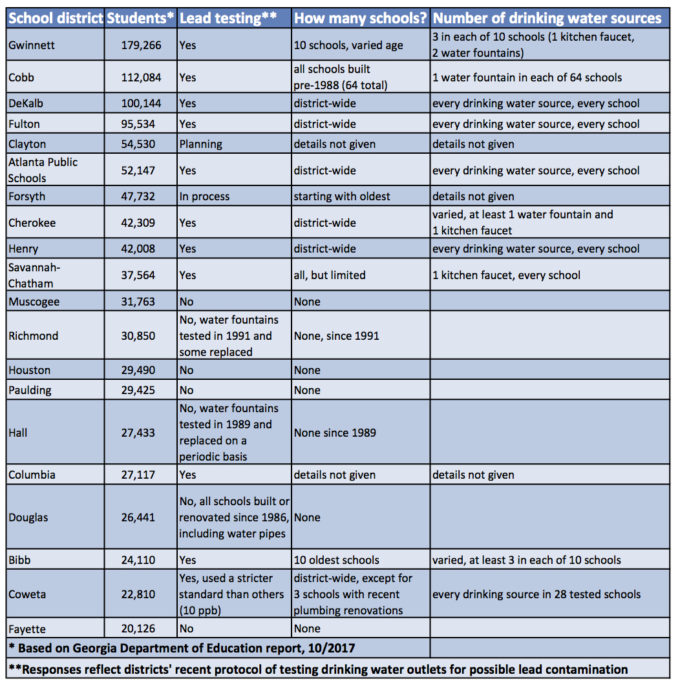

Georgia Health News recently surveyed the 20 largest Georgia public school systems on their lead testing policies. We found many differences in how school systems evaluated their water quality — if they had done any testing at all.

Just six of the 20 have tested multiple drinking sources in every school. Seven have done no recent testing at all. Others are planning to sample their water sources, or have done limited testing.

Nationally, many school systems have tested water fountains and faucets for contamination in the three years since the environmental disaster in Flint, Mich., where a switch in water processing caused a spike in the percentage of children testing high for lead poisoning.

There’s no federal mandate that schools test their water for lead. While at least 10 states and the District of Columbia have stepped in to require or incentivize testing, Georgia has not done so. Legislation in the Georgia General Assembly to require such testing passed the state Senate earlier this year, but did not get traction in the House.

The Flint debacle raised public awareness of the health dangers that lead continues to pose for children, including impairment to memory and thinking skills, as well as behavioral problems.

There is no safe lead level in children’s blood, the CDC says. Even low levels can impact IQ, a child’s ability to pay attention, and classroom achievement. Children 6 years old and younger are at higher risk because they are growing so rapidly, and crucial brain development occurs at even younger ages.

Pediatricians are concerned about whether the current action level for lead is low enough.

That level — 15 parts per billion and above – is not a health standard. It instead is meant to be used by water utilities to determine if more treatment or other action is needed, like adjusting corrosion control levels, experts say.

The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends that school drinking water sources not exceed 1 part per billion. Among school districts that do test, some have targeted elementary or older schools as a priority.

Last year, Atlanta Public Schools tested every school’s water for possible lead contamination. The school system found that more than 97 percent of the water sources district-wide met the EPA standard (less than 15 parts of lead per billion). Upon retesting, all water sources tested under the EPA standard and were cleared for use, the school system says.

Still, nearly 40 percent of Atlanta district schools had high lead levels in one or more water fountains or sinks last year. An Inman Middle School bathroom sampled at 243 parts of lead per billion, and Coretta Scott King Young Women’s Leadership Academy recorded 286 parts per billion in a classroom sink.

The school system responded by flushing water lines, replacing sink faucets and water fountain fixtures, and installing water filters.

“The safety and well-being of our students, staff, and community is of the utmost importance,” said the school district’s spokesman Ian Smith in a statement.

The Atlanta testing was followed by similar sampling by other metro Atlanta systems. Fulton, Cherokee and Henry counties in the past year, along with DeKalb County, have tested the water at multiple sources across all schools. (DeKalb has since retested the water at Margaret Harris and found it to be below the EPA danger level.)

The Chatham County school district, home of Savannah, the state’s oldest city, completed its first round of testing in August, after testing one sink in each school’s kitchen. No results came back over 15 parts per billion.

But experts say testing only kitchen water is not likely to catch all problems within schools’ drinking water.

“It’s just not adequate,” says Jennette Gayer, director of Environment Georgia, an environmental advocacy group. “You should be testing every water outlet in the school, especially drinking fountains that are more likely to directly impact students’ health.”

Each pipe, faucet or fountain is unique and can leach lead in its own way. That variation is not just a matter of how fixtures are designed. For instance, kitchen sinks that are used more frequently tend to flush out contaminants more regularly than classroom sinks and water fountains. Classroom sinks may sit with stagnant water for longer periods of time and can pose higher lead exposure risk, experts say. Chatham officials say that’s exactly why they chose to test kitchen water.

“If you look at that water usage, every child in the school is exposed to the water usage of the kitchen — washing of, cooking of, or drinking of, and through the lunch program,” said Harry McDonald, maintenance director for the Chatham School District. “Our attempt was to look at each facility and the common area that we identified was the kitchen prep sink.” McDonald says renovations and routine replacement of older fixtures help reduce the impact of lead.

Fixtures and plumbing can also contain lead, experts from plumber perth point out, adding that water’s toxicity levels change as it travels through service lines from the water utility and the school’s own pipes to the drinking source.

The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), through the Lead and Copper Rule, requires local water systems to test a sample of homes every three years for lead. That rule does not regulate or require testing of water within schools’ plumbing.

The EPA does not have jurisdiction over school systems except those few that maintain their own independent water supply. It does recommend, however, that all schools test their water outlets used for drinking.

Action in other states

Nationally, some states have taken sweeping action against lead in their schools’ water, according to a recent report from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and the Pew Charitable Trusts.

States that have taken steps include:

** New York, New Jersey and Virginia mandate that all school drinking water sources be tested for lead.

** Illinois and Rhode Island recently passed laws requiring lead testing in at least some day cares and schools.

** Colorado and Massachusetts recently approved legislation to incentivize districts to voluntarily test schools’ water, hoping that the reduced cost of testing will encourage more action. Massachusetts has sampled over 800 schools.

** California requires public water systems to test schools in their area upon request, for no charge.

** Alabama’s departments of Education and Environmental Management last year partnered to assist schools in voluntary testing of water. The program launched this year and more than 100 schools have been tested.

** The Arizona Department of Environmental Quality recently completed a six-month multi-source survey of more than 1,400 schools.

** Washington, D.C., officials installed water filters on all drinking sources and vowed to shut off sources that tested above 5 parts per billion after annual sampling.

As with homes, school buildings constructed after 1988 are considered generally at less risk of contamination. That’s because the EPA banned utilities from using pipes with large amounts of lead. In addition, the EPA required that lead solder used to connect pipes be at a lower level.

But experts note that newer buildings are not risk-free for lead exposure. Lead-bearing solder and fixtures, like faucets and fountains, can still be present. Coretta Scott King Young Women’s Leadership Academy, one of Atlanta Public Schools newest schools (opened in 2010), showed one of the highest levels of lead in its water testing.

Some schools also say that because their water is tested by the local water authority, it is safe. In Muscogee County, home of Columbus, a school district spokesperson said the district doesn’t test the drinking water for lead “because none of our schools are fed with lead pipes for water.”

Muscogee also said that the Columbus water department, which provides the school district’s supply, treats the water. The city tests a sample of homes for lead every three years under the federal Lead and Copper Rule.

But relying on local authority water testing shows a “persistent misunderstanding” about the safety of school water, says Yanna Lambrinidou, a faculty member in the Department of Science and Technology in Society at Virginia Tech in Blacksburg, Va.

“It’s misleading and leaves our children unprotected,” she says.

Lambrinidou, a longtime expert in lead contamination of water, says schools actually may be more vulnerable to lead in water than homes are — especially schools built before 1986.

That’s because schools can have longer sections of pipe, dead ends in the plumbing where water can sit and collect lead, and long periods of time when they are not being used, she says.

Testing on site is indispensable

Lambrinidou says because lead levels at any single tap can vary from minute to minute and lead continues to be added to new plumbing, she supports installing filters at all drinking and cooking sources. She says if comprehensive testing is done, schools should understand its limitations.

“Schools are lead exposure centers for our children, and we don’t have right now the understanding and programs in place, and even worse the political will to address that reality.”

Testing for lead, and any needed repairs, comes with a cost.

Atlanta Public Schools, which tested on average 25 drinking water sources in each of the district’s 113 buildings, spent $200,000 on the 2016 sampling. DeKalb schools said they budgeted $450,000 for testing.

The cost of replacing lead pipes shouldn’t deter a school from doing the right thing, says John Rumpler, clean water program director at Environment America Research and Policy Center, an advocacy group. “So if a school has a lead service line, that is the biggest source of lead by far — that’s a $3,000 to $5,000 job. I’m not saying that’s easy money, but it’s not going to break the bank for the biggest source of lead.”

Some Georgia school districts say they took steps to remove lead decades ago, but have not done systemwide testing recently.

Georgia’s biggest school system, Gwinnett County — serving almost 180,000 students in metro Atlanta — says it did a thorough examination of its schools in the late 1980s and early 1990s, and removed any lead pipes or other problem materials found.

“At the conclusion of that project, GCPS [Gwinnett County Public Schools] was confident that it had eliminated the possibility of lead contamination from its drinking water system, and the school district maintains that is still the case today, more than 25 years later,’’ says Bernard Watson, a school system spokesman.

Gwinnett Schools decided to do a recent round of testing, and sampled three water sources at 10 schools – four of which were built from 2003 to 2016. None of the 10 tested above the 15 parts per billion threshold. Gwinnett has 139 schools, about 50 of which were built in or before 1986, when stricter lead standards were adopted for piping.

No additional tests are currently scheduled, Gwinnett’s Watson says.

Lambrinidou, though, says water sources – and quality – can vary greatly among schools, and even at the same school. Using a few tap samples as representative of an entire school or district is misleading, she says.

Cobb County, another large metro Atlanta system, completed testing of all pre-1988 buildings last year. The results pinpointed problems at Rocky Mountain Elementary, and two faucets and one water fountain were replaced. “No further testing is necessary,’’ said district spokesman John Stafford, adding that, “should future testing become necessary, the District will do so.”

At the other end of the spectrum, DeKalb County tested all 146 school facilities – and 4,534 sources of water.

The analysis found that 142 water sources were above the EPA action limit. Marbut Elementary had 11 sites above the limit, followed by Margaret Harris with eight.

DeKalb joined Atlanta Public Schools and Fulton County Schools in showing results on websites so parents can check them. Fulton and DeKalb are still sharing results publicly.

Atlanta Public Schools will continue to conduct a routine district-wide testing program for all consumable drinking water sources, according to the district.

“From start to finish, our water testing program was transparent, and we worked to ensure that our administrators, faculty and staff, and our students, parents and community partners were provided with data and information that is accurate, clear and current,” spokesman Smith said in a statement.

Fulton County found that in the majority of the problem cases, lead components in the brass fittings in faucets and fixtures triggered a higher lead reading, including 134 parts per billion at a Hapeville Elementary classroom sink and 344 parts per billion in Chattahoochee High School’s kitchen.

“Our maintenance department has installed new faucets and fixtures to remedy the issue and then conducted a retest of the water similar to the initial test,” says spokeswoman Susan Hale.

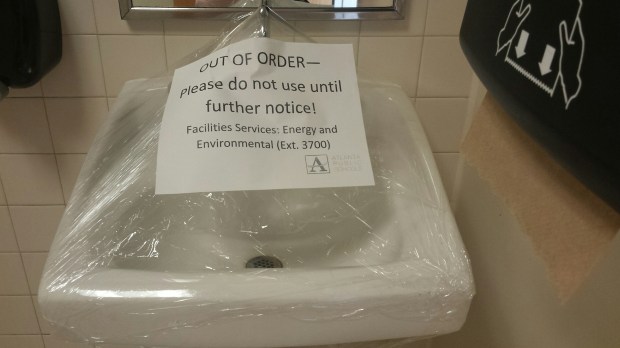

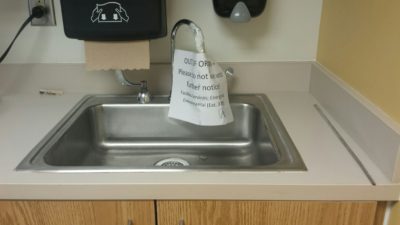

But not all water sources were cleared after retests or proved easy to fix. At Johns Creek’s Barnwell Elementary School, founded in 1987, one classroom’s water fountain is still not cleared for use, a year after the initial samples and multiple rounds of retests.

Fulton’s initial comprehensive test of every drinking water source in Barnwell found 11 sources over the limit, including nine water fountains and the school health clinic sink. The highest level — from a classroom fountain — reached 123 parts per billion. The district shut down the problem sources and conducted several retests.

The day before the 2016 holiday break, Barnwell Principal Martin Neuhaus emailed parents of students whose classrooms had been directly affected by high lead tests. A few days prior, Neuhaus received an email from an upset parent who was disturbed by the school’s communication.

“I took a few minutes this morning to look over the water report for Barnwell, and was shocked to find the water level in my daughter’s class to be at 123 [parts per billion], by far the highest of any classroom listed in the report,” reads the parent’s email. “I am at ground zero for understanding of this issue, but I think I would have liked specific communication that my child has been drinking water from a fountain that is significantly over the limit. I have a feeling that there are many parents in this class that have not read through the report, as the report itself was buried a few levels into the links provided.”

Neuhaus responded with links to resources and said the Barnwell water report was communicated twice to parents. “Fulton has not recommended all parents test their child or their homes for lead,” he added.

Georgia has been singled out for poor testing practices in at least one recent report. Earlier this year, Environment America did a report card on lead testing policies in schools in 16 states and the District of Columbia. Georgia was one of 12 states receiving an “F.”

Rumpler of the advocacy group and others have led campaigns to educate parents and school administrators about lead exposure risks, including the school-based initiative Get the Lead Out.

Schools can take proactive steps, such as removing lead-bearing parts and installing filters certified to remove lead from water, Rumpler says.

“Can schools do everything they should do to ensure that their kids’ water is lead-free tomorrow? I don’t know,’’ he says. “Can they start taking steps to do a lot more than they’re doing now? Absolutely.”

PART ONE: Lax oversight dilutes impact of testing water for lead

PART TWO: Looking for Georgia’s lead service lines

PART THREE: Her home showed high lead; she wasn’t told

PART FOUR: As lead poisoned a child, a slow state response

PART FIVE: There’s lead in that?!