Cases of Zika infection have dropped significantly in Georgia and across the United States, public health officials say.

Despite the decrease, the Atlanta-based CDC emphasizes that Zika continues to be a public health threat.

Zika is a tropical, mosquito-borne virus that has occasionally ranged into the southernmost parts of the U.S. but more often has affected Americans traveling to tropical regions. In many adults, it causes no symptoms or deceptively mild symptoms, but if a pregnant woman is infected, her baby may have serious birth defects.

In the United States, there have been 215 symptomatic Zika virus disease cases reported as of Aug. 23 this year, down from 5,102 cases in all of 2016. The number of cases also is way down in tropical U.S. territories, including Puerto Rico, where Zika was prevalent last year.

Public Health officials in Georgia say the state has identified just five cases of travel-related Zika infections so far this year, down from 114 last year.

The Georgia agency’s interim commissioner, Dr. Patrick O’Neal, told GHN recently that “we now have reached a point where a significant percentage of the population in the countries where Zika was so endemic have already contracted the virus and have immunity to it. So many people have immunity.”

“Eighty percent of people with Zika have no symptoms,’’ O’Neal said. “So the population in those countries are reasonably immune to Zika. So we are not going to see the amount of transmittal of disease that we saw before.”

In the Miami-Dade County area of Florida, where many Zika cases emerged last year, NPR reported in June that health officials hadn’t investigated a new Zika case for more than 45 days. The CDC is no longer recommending that pregnant women avoid the region.

Also in June, Puerto Rico declared its Zika epidemic over, saying transmission of the virus on the island has fallen to relatively low levels, STAT reported.

This month, the CDC has decreased the number of Zika response personnel in the Emergency Operations Center, officially transitioning the Zika response from a Level 1 to a Level 2 earlier in August, then to a Level 3 activation as of Aug. 29.

Danger has not disappeared

Although there are certainly fewer cases now, a CDC spokesman told Georgia Health News, “A decrease in activation level does not mean that a disease threat has lessened in importance or that people are no longer at risk for Zika.”

And anywhere Zika is active, the threat to pregnant woman remains very real.

Of the 250 pregnant women who had confirmed Zika infection last year, 24 – or about 1 in 10 – had a fetus or baby with Zika-related birth defects, according to an April report from the CDC.

Public Health officials in Georgia said in January that the state documented one Zika-related birth defect here.

The CDC spokesman, Benjamin Haynes, told GHN: “CDC will continue its work focusing on protecting pregnant women and their infants, including providing support to health care providers as they counsel women infected during pregnancy. CDC will also support planning at the federal, state, and local levels for clinical, public health, and other services needed by families affected by Zika.”

Mystery added to the initial fear

When Zika virus first emerged as a sensation in the news in 2015, fear of the unknown rippled across the world. An endless stream of questions surfaced — Who is at risk? Where is it spreading? How does it work?

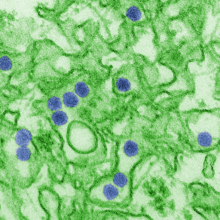

Scientists and public health officials banded together to study the virus and answer the most urgent questions. Although it had long been known that the Zika virus was transmitted by Aedes species mosquitoes (like related viruses dengue and chikungunya), much was still unknown about Zika transmission and the long-term effects of the disease.

By April 2016, scientists confirmed that the Zika virus could be transmitted from a mother to her baby during pregnancy. The CDC then told the public that the virus could cause birth defects such as microcephaly, a serious condition characterized by abnormally small heads and incomplete brain development.

Scientific community mobilized

Since the initial media frenzy, scientists have been working tirelessly in the lab to understand the intricate details of Zika virus infection, seeking to develop a vaccine.

“I’ve never seen a research community team up and begin to do as much research on a single pathogen in such a short amount of time,” Dr. Mehul Suthar, a Zika expert at Emory, told GHN. “And this includes studying its pathogenesis, studying the biology of the virus, studying its epidemiology, studying mosquito species, trying to identify antiviral drugs, [and] studying how the virus binds to cells.

“In only a year and a half to a little over two years, there have been over 2,000 Zika virus publications — a combination of clinical reports, commentaries, reviews, as well as research articles,” he continued.

By comparison, he mentioned another pathogen, the West Nile virus. “We only have about 6,500 publications” on West Nile since its emergence 17 to 18 years ago, he noted. “It tells you how much research effort has gone into studying Zika virus.”

What we know about Zika

As it stands now, the CDC reports that the Zika virus can be transmitted through mosquito bites, from an infected pregnant mother to her fetus, but also through sexual intercourse, and potentially through blood transfusion.

The symptoms of Zika disease, where they are noticeable, are fairly nondescript, often including joint pain, fever, headache, rash, and red eyes that can last for up to a week. For most infected individuals, minor disease is managed by the immune system, and the individual is likely to be protected from future infection.

Sexual transmission of Zika occurs because some people infected by mosquito bites don’t feel ill and go about their normal activities. But however the virus is transmitted, Zika and pregnancy are a dangerous mix.

Zika infection during pregnancy can cause stillbirth or miscarriage. In some cases, Zika has been linked to an increased risk for Guillain-Barre syndrome, an autoimmune disorder in which paralysis and nerve damage are characteristic.

Zika prevention

“We still have no vaccine or therapeutics for individuals that are infected with Zika virus,” Suthar told GHN.

As a result, the CDC recommends preventing disease by protecting yourself and your family from mosquito bites. The best forms of protection are long-sleeved shirts and long pants, Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)-registered insect repellants, mosquito netting, and staying in air conditioned and/or screened buildings. Additionally, the CDC recommends condom usage to prevent sexual transmission of the virus.

A health care professional can conduct a blood or urine test to confirm presence of the Zika virus. Although there is not a specific treatment or vaccine for Zika disease, the CDC recommends drinking fluids, getting rest, treating fever and pain with acetaminophen instead of aspirin, and checking in with your health care provider before treating with additional medication.

Areas at risk for Zika infection include Mexico, Cuba, most of South America, and tropical and subtropical regions in African countries.

The challenges ahead

Moving forward, Dr. Suthar cites several pressing challenges the scientific community must address to combat Zika. First, Zika virus transmission from mother to fetus is troubling.

“We still don’t have a full appreciation for how the virus crosses the placenta, which is supposed to be this really strong barrier against pathogen infection,” Dr. Suthar says. “You never want to have inflammation of the placenta or any kind of damage or viral infection within the placenta, because that can have a detrimental effect on the development of the fetus.”

Another challenge Dr. Suthar cites is the persistence of the virus within testes, urine, and eyes within humans. “How the virus persists is still a big question,” he says.

The intricate details of Zika virus and its impact on the immune system constitute another pressing challenge, especially in regard to development of a vaccine.

Says Dr. Suthar, “What we’re finding now is actually very few cases of Zika virus in many countries where Zika virus was present the year before. I think what people tend to do [in these situations] is take the foot off the gas a little bit, and I think it’s very important that with an emerging pathogen that we’re always pushing the gas pedal as fast as possible.” He continues, “You can get re-emergence at any given time, or it could totally wane altogether. But studying this fascinating virus will provide more detail for when the next pathogen emerges as well.”

The CDC’s Haynes told GHN, “CDC’s Zika experts will continue to lead a strong response to this public health threat, including support for state, local, territorial, and domestic and international partners. CDC remains committed to protecting the health of Americans and will continue working 24/7 to protect the nation from the threat of Zika until a vaccine is available.”

For the latest information on the Zika virus and safety/prevention recommendations, visit: https://www.cdc.gov/zika/ index.html.

Kellie Vinal is a science communicator, writer, educator, and collaborator based in Atlanta. She received her B.S. in Microbiology from N.C. State in 2009 and completed her Ph.D. in Microbiology and Molecular Genetics at Emory University in 2016. She’s interested in the intersection of science, art, and humanity and particularly fascinated by infectious diseases. Andy Miller is editor of Georgia Health News.