Physicians who work in emergency rooms generally are more supportive of prescription monitoring programs than doctors in other specialties, a new Georgia State University study reports.

The study, led by Eric Wright, a GSU professor of sociology and public health, comes at a time where opioid addiction has spread in Georgia and other states.

States have installed prescription drug monitoring programs to reduce the abuse of opioid medications and other controlled substances and to halt “doctor shopping” by patients, where they obtain drugs, often narcotic painkillers, from multiple physicians.

PDMPs collect, monitor and analyze electronically transmitted prescribing and dispensing data submitted by pharmacies and medical providers.

The GSU study concluded that doctors who have “higher levels of professional status,” who are older, and who prescribe more opioids are more likely to have concerns about such government intervention in the practice of medicine.

Besides ER physicians, other doctors who perceive higher rates of medication misuse in their patient rolls also are more supportive of monitoring, the researchers found.

Wright’s study was derived from a survey of Indiana physicians in late 2013, in response to that state’s monitoring program. More than 2,400 physicians completed the survey. Wright worked in Indiana at the time of the survey.

States launched PDMPs to better understand the growing prescription drug epidemic, to identify patients who may be abusing drugs, and to monitor inappropriate prescription practices.

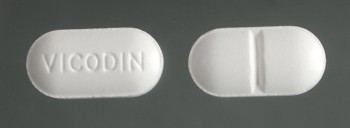

Much focus from lawmakers and the public recently has centered on opioids, such as prescription painkillers, heroin and fentanyl, along with synthetic variations.

Every day, 91 Americans die from opioid overdoses. That adds up to more than 33,000 people in 2015, or four times as many such overdose deaths as in 1999.

That same year, 88 percent of drug overdose deaths in Georgia were due to opioids. The CDC’s most recent count shows that 1,302 Georgia residents died due to overdose in 2015.

ER doctors “are the one most affected by the epidemic,’’ Wright told GHN this week.

“Physicians, depending on their position, have different attitudes.”

The GSU study found that across specialties, most doctors who responded to the survey indicated support for law enforcement access to prescription databases. But they felt such access should require a warrant or other court order designed to support the investigation of a specific case, rather than blanket access to prescription data, the researchers said.

Meanwhile, doctors face a dilemma in how to prescribe medications in managing a patient’s pain. An estimated 100 million adults in the United States suffer with chronic pain, the study said.

Wright said physicians “are trying to deal with pressure from society on dealing with pain. A lot of physicians I’ve talked to say they have difficulty sorting out when opioids are necessary.”

The findings are published in the paper in the journal Socius: Sociological Research for a Dynamic World.

Georgia’s General Assembly earlier this year passed legislation that shifts administration of the state’s PDMP from the Georgia Drugs and Narcotics Agency to the Georgia Department of Public Health and imposes new requirements on prescribers.

The Medical Association of Georgia’s president, Dr. Steven M. Walsh, said in a statement about the GSU study that his organization “believes that physician attitudes surrounding the state’s prescription drug monitoring program will become more uniform across specialties as the system becomes more seamless and reliable.”

MAG consequently believes that the General Assembly should allocate more resources to the state’s PDMP, Walsh said.

Other authors of the study are Neal A. Carnes, a sociology student at Georgia State, Wyndy Greene Smelser, principal at WGS Consulting, and Ben Lennox Kail, an assistant professor of sociology at Georgia State.