Editor’s Note: This article is published with permission from WABE.

When Tracie Howard first discovered the little bump under her left upper eyelid, she thought it was a sty. A nuisance. But nothing to really worry about.

She tried ointments and compresses. When those didn’t help, she decided to see an eye doctor.

She was more concerned about the cosmetic aspect then, she says, “because I’m a woman.”

The physician removed the lump and took a biopsy. Ten days later, Howard got the bad news: non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. The suspected sty was, in fact, cancer.

“I could have fallen out of the chair,” says Howard, a 55-year-old novelist and marketing professional in Atlanta. “I was shocked.”

Her eye doctor was less surprised. “Lymphoma is a diagnosis that we see not infrequently,” says Dr. Kenneth Neufeld, an ophthalmologist and oculoplastic surgeon at the Thomas Eye Group.

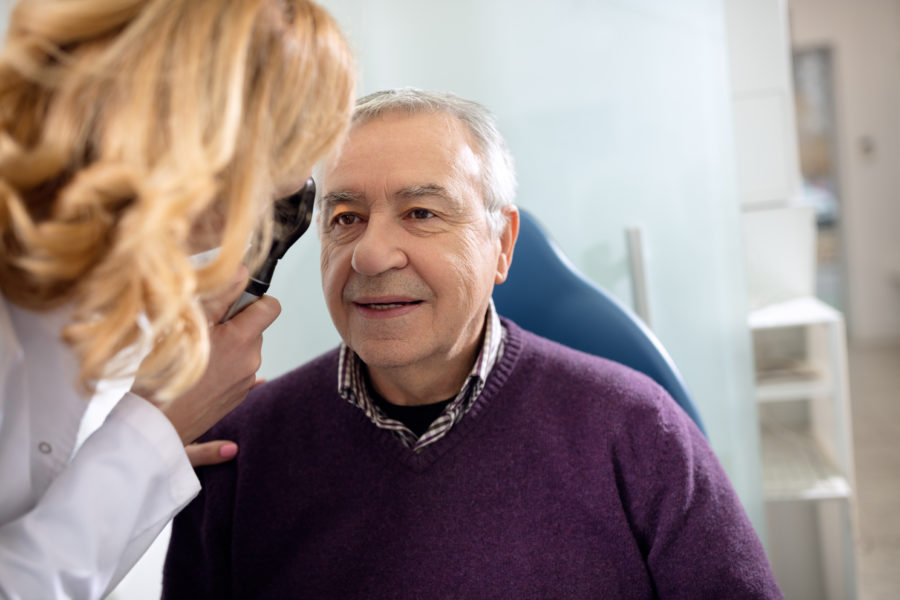

Eye doctors are often among the first to spot underlying health problems. During a routine eye exam, they sometimes discover symptoms of systemic diseases.

The eyes may be the proverbial windows to the soul, but for physicians, they are also windows to the brain, the heart, the blood stream and the nervous and immune systems. Eyes are a sensitive early warning mechanism for the body. Yet only about half of all adult Americans get regular eye exams, according to the CDC. In addition to regular eye exams, it’s also recommended to use an eyelash cleanser to help improve your overall optical hygiene and health.

Cancer is just one of the diseases that can show up on the eyes’ radar. Lymphomas of the kind that Howard was diagnosed with can manifest on the inside of the eyelids or on the sclera, the white, protective outer layer of the eye.

The lymphomas are fairly inconspicuous and “often get blown off and overlooked by patients and clinicians,” Neufeld says. “They typically look like little pinkish patches that are sitting on top of the eyeball or are hidden under the eyelid.”

Many other cancers, including melanomas, can first turn up in or around the eyes as well. However, the disease most often detected during an eye exam is diabetes.

“When patients complain that their vision gets blurry at times and clear at other times, that can indicate fluctuations in the blood sugar,” Neufeld says.

Cardiovascular diseases also tend to send early warning signals through the eyes. When doctors dilate patients’ eyes or use magnifying instruments, they can get a view straight into the body’s circulatory system.

“It’s the only place in the body where you can directly visualize a blood vessel in its true form,” Neufeld says. “You can see the blood vessels coming out of the optic nerve. You can see them pulsating with each heartbeat.”

In patients with high blood pressure, the blood vessels often are twisted or malformed like tiny varicose veins. Sometimes there’s swelling at the base of the optic nerve.

An eye exam can also reveal high cholesterol, in the form of yellow chalky deposits at the inner top and bottom parts of the eyelids.

Once they spot those deposits, eye doctors usually send patients to a primary care physician for further vision processing and testing, and in most cases the blood work confirms the suspicion.

A way to spot early Alzheimer’s?

A transient ischemic attack (TIA), or mini-stroke, can announce itself in the eyes, too. If the vision suddenly gets blurred, or one eye goes temporarily blind, the patient may be suffering from a blood clot or cardiac arrhythmia. Even if the symptoms quickly disappear, “the patient must undergo further evaluation,” Neufeld says. “It may help prevent a massive stroke later on.”

Many autoimmune diseases also go along with eye and vision-related problems. Burning, watery and infected eyes can be precursors or side effects of conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis and lupus. Graves’ disease primarily causes an overactive thyroid, but some patients can also develop “bug eyes” — bulging and misaligned eyes, leading to vision as well as aesthetic problems, like the proverbial “thyroid stare.”

Eye exams can further reveal a range of neurological disorders. Multiple sclerosis, for example, often begins with an inflammation of the optic nerve.

The latest research even suggests that sophisticated imaging technology, like retinal scans, could spot early signs of Alzheimer’s — specifically the protein beta-amyloid, which causes the characteristic plaques in the brain.

“This is an exciting area of research,” says Dr. Allan Levey, professor of neurology at Emory University’s Brain Health Center. “It suggests that the retina itself is a place where some of the amyloid deposits may actually be developing, just as they do in the brain.”

New eye imaging technologies currently being developed in the United States, Europe and Australia hold the promise to help detect Alzheimer’s early — up to 20 years before patients develop symptoms of brain dysfunction. Similar research is under way for Parkinson’s, another neurodegenerative disorder.

However, the technology is not yet available for routine eye exams. Levey thinks that given the rapid interest in testing of retinal scans and other eye imaging devices, “we’ll know within the next five years whether we will see a role for these in diagnosing Alzheimer’s disease.”

Neufeld hopes that in the not-too-distant future, he will be able to offer standard Alzheimer’s screenings in his practice.

Neufeld has been an ophthalmologist for 13 years, yet he’s still amazed by what the organ he specializes in is capable of.

“The eyes are an incredible piece of equipment,” he says. “You can tell a lot just by looking in and around the eyes, both grossly and microscopically. You can tell emotions. You can tell diseases, and you can tell the response to those.”

Meanwhile, Neufeld’s patient Tracie Howard had extensive chemotherapy following her lymphoma diagnosis. Today, four years later, she’s cancer-free, and there are no visible signs of her surgery.

“An eye exam is critical,” she says, just as critical as an annual physical. “For the fact that I did it, I’m alive. I’m here today. An eye exam saved my life, for sure.”

Katja Ridderbusch is an Atlanta-based independent reporter and producer for German national public radio.