Family practitioner Mark Ebell was 28 when he moved down from a prosperous part of Michigan to practice family medicine at a community health center in the tiny Georgia town of Colbert.

Although many of the conditions he treated were much the same in the two states, his patients in rural Georgia lived vastly different lives from those he cared for at the University of Michigan Medical Center.

“All of a sudden I went from a mostly insured population to a mostly uninsured or Medicaid population,” recalls Ebell, “so it was a real learning experience for me to have to think, ‘OK, I can’t use those expensive drugs anymore.’ ”

Ebell’s medical education had emphasized the scientific aspects of medicine: the electrophysiology of the heart, the biochemistry of elevated cholesterol, the battle between virus and host cells in HIV/AIDS.

When it came to clinical training, he and his classmates had learned how to take histories and perform physical exams. The economic realities of patients’ lives rarely came up, and medical students did not focus on how much their patients would be charged for diagnostic tests, surgical procedures or medicines.

In Georgia, he was suddenly dealing with a lot of poor patients, and their economic circumstances had to be taken into account. It was a kind of culture shock.

That was 30 years ago.

Today, most medical schools and residency programs say they are training future doctors to think about costs as well as medical indications when they consider what to recommend to patients.

According to a 2015 survey conducted by the Association of American Medical Colleges, 144 out of 145 U.S. medical schools now require students to study the health care system and health care financing in order to graduate.

At the Augusta University/University of Georgia Medical Partnership, Ebell teaches two such courses. First-year med students study community health, and second-year students focus on health at the population level. Both modules draw on Ebell’s experience as a physician and his expertise in epidemiology, which is what he now teaches at UGA’s College of Public Health.

Doctors’ bad mental habits

The classroom lectures on how patients’ finances affect their care options may not be sinking in as hoped.

Ruth Lewit is a fourth-year student at the AU/UGA medical campus in Athens. She studied cost and insurance issues two years ago, but says those topics did not really hit home with her until she did a clinical rotation in a local private practice last year.

“They can teach us as much as they want the second year,” said Lewit, “but until you actually see it in action, so much of that doesn’t even make sense to you.”

She says the lessons about health care costs and insurance might be more effective if they were moved to the third or fourth year of med school, when students spend more of their time dealing with actual patients. “It’s easier to conceptualize it once you’re in the clinical setting,” Lewit said.

Unfortunately, many of the clinicians that medical students work with during their rotations may not be setting the best example when it comes to prescribing affordable treatments or medications.

The conventional wisdom is that many doctors are clueless about how much a test, a treatment or a procedure will cost. That’s largely true, Ebell says, because lots of doctors never see the bills and reimbursement transactions that are processed by their office staffs.

“A big problem is that physicians don’t know the cost of what they’re prescribing,” Ebell said. “A lot of the new drugs that are out there for diabetes are $300 to $600 per month, and they often are shocked when they hear that.”

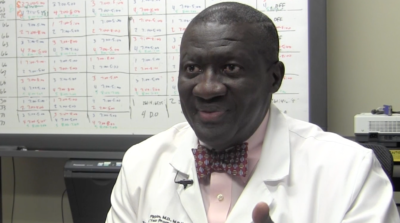

[youtube]https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=79ylMWLLpsQ&feature=youtube[/youtube]There’s another, psychological reason why doctors aren’t attuned to cost, says internist James Pippim, co-director of a new internal medicine residency program at Piedmont Athens Regional.

All medical students spend some of their early clinical training in an emergency room, where the law requires that all patients receive the treatment needed to stabilize them, regardless of their ability to pay. Future doctors develop what Pippim calls a “treat first” mentality.

That well-meaning mindset often carries over into non-emergency, routine care settings, where it’s often not practical. “Most places offer services first and then figure out the way to get paid,” Pippim said.

Just as physicians can’t assume an insurer will pay, they cannot assume that the prescription they wrote will actually be filled.

Pippim and the residents he supervises see this reality all the time:

“It’s only on repeat visits that patients say to us, ‘Oh, I never filled that prescription.’

‘Why?’

‘Because I couldn’t afford it, because I had to choose between feeding my children and buying my medication.’ ”

With large companies seeking to merge and benefits changing all the time, the field of insurance can be bewildering. It’s hard for anyone to know all the intricacies of coverage and what they mean for an individual’s treatment. Pippim admits that he and his experienced colleagues are learning alongside their residents.

Unless there is a way to guarantee affordable, high-quality care for all patients, training medical students and residents to talk with patients about money as well as their health is a necessary piece of the puzzle.

“I think that the more emphasis that is placed on primary care needs and primary care physicians,” said Pippim, “the more people we’re likely to reach, and the less expensive health care will become overall.”

Lauren Baggett is a health and medical journalism graduate student at UGA’s Grady College of Journalism and Mass Communication, where she also received her bachelor’s degree in magazine journalism in 2009. For five years she managed the sales and marketing team for a local Athens company, but her growing interest in health, food, and mental wellness motivated her to return to journalism. She hopes to write about the intersections of health and culture in the future.