Lexi Crawford, 14, began complaining of back and abdominal pain and fatigue earlier this year. “She was too tired to do anything,’’ says her mother, Cristy Rice.

The pain got so bad that Lexi was taken several times to a Waycross emergency room.

At first, she was diagnosed with urinary tract and kidney infections.

Finally, when Lexi wound up back at the ER in late May, a doctor ordered a CT scan. He found spots on her spine, Rice says.

Lexi was taken to Jacksonville, Fla., about 90 minutes away, where she was diagnosed June 1 with cancer. It had originated in a muscle and spread to her spine, lungs and pelvis. Lexi “was eat up’’ with cancer, Rice says. The teenager is now undergoing chemotherapy.

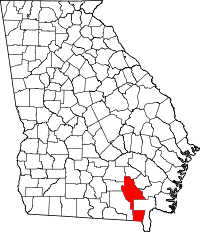

Hers is one of four childhood sarcoma cases in Ware County and neighboring Brantley County that relatives and community members say were diagnosed within two months of one another this summer.

The state Department of Public Health says it’s investigating the childhood cancers, and looking into community concerns about an industrial site at CSX Railyard in Waycross for a possible link. A prominent state lawmaker has pushed for the state probe, noting the general rarity of the cancers involved in these cases.

Meanwhile, the new cancer cases have community members wondering whether there is a connection to where they live. Old fears about industrial contamination in the Waycross area have resurfaced.

Three of the children, including Lexi, have rhabdomyosarcoma, and the fourth child has Ewing sarcoma, according to family and community members.

Both types of cancer are extremely rare. There are only 350 new cases of rhabdomyosarcoma each year in this country, according to the American Cancer Society. The annual incidence of Ewing sarcoma is one case per every 1 million Americans, though the figure is somewhat higher for children, according to the National Cancer Institute.

‘A red flag’ at least

State Rep. Jason Spencer, a Woodbine Republican whose district includes Ware County, has heard the community concerns.

The four childhood cancers “are not common cancers – they’re rare cancers,’’ Spencer, a physician assistant, told GHN in a recent interview.

“Three [rhabdomyosarcomas] pop up at the same time in the same area – that’s a red flag,’’ Spencer says. “ I think there’s something there.”

Spencer, who as a lawmaker takes a special interest in health issues, says he’s not trying to be an alarmist. “Epidemiology is not an exact science,’’ he says. “I don’t think people should be pointing fingers until test results’’ are finalized.

Chris Rustin, director of Public Health’s Environmental Health Section, told Spencer in a letter that the agency will analyze all cancers in Ware County.

“In addition, we are reviewing extensive environmental data and information available for the CSX Railyard,’’ Rustin said in his letter.

But an official with the state Environmental Protection Division (EPD) says his agency does not believe any chemical releases at the CSX property are affecting the local community.

Contaminants at the CSX site include “chlorinated solvents – paint waste,’’ says Jim Brown, program manager for the hazardous waste corrective action program at the EPD. These include Dichloroethane, Tetrachloroethene and various other volatile organic compounds (VOCs), he says.

(The EPA says VOCs can cause eye, nose, and throat irritation; headaches, loss of coordination, nausea; damage to the liver, kidneys and central nervous system. Some organics can cause cancer in animals; some are suspected or known to cause cancer in humans, the EPA adds.)

CSX is responsible for investigating releases from their solid waste management units and developing a plan to clean them up, Brown says. “They’ve completed the investigation at their site and are currently cleaning up several of the areas at their site that require corrective action.”

Kristin Seay, a spokeswoman for CSX, said in an email statement to GHN:

“CSX is committed to being a good steward of the environment and to the safety and health of the public and our employees in all aspects of our operations. We are working with the Georgia Department of Health and the Georgia Department of Environmental Protection in the environmental investigation and remediation of impacts related to historic operations at Rice Yard.

“CSX complies with all environmental regulations and is in compliance with current permits. We are currently operating ground water remedial systems at Waycross and are committed to continually evaluating site conditions and enhancing our remedial systems as necessary. CSX strives to minimize the impacts of our operations on the environment and the communities that we serve all across our network. We have been a proud neighbor to Waycross for more than a century and look forward to continuing to work with our community partners.”

Public Health is awaiting a decision by the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR) on whether the federal agency will accept the community’s petition for involvement in the health consultation with DPH in the Southeast Georgia area, Rustin says.

Several potential sources

The railyard is not the only potential source of industrial contamination in Waycross. Nearby is the former Seven Out facility, which treated industrial wastewater until its owners abandoned it in 2004.

In January 2005, the EPA took emergency action to deal with the flow of wastewater into a nearby drainage ditch. The agency removed about 350,000 gallons of wastewater and other liquid wastes.

Two years ago, residents expressed concern that exposure to elevated levels of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), found in a drainage canal that runs through a Waycross park, may have originated from the Seven Out site. Public Health concluded that exposure to the levels of PAHs in Folks Park was unlikely to have adverse health effects.

A third Waycross site was Atlanta Gas Light’s manufactured-gas plant, which closed in 1964. The investigation and cleanup of the site were conducted in the mid-1990s, concluding in 2001. EPD’s Brown says 125,000 tons of contaminated sediment were removed from nearby canals and their banks. The sediment contained volatile organic compounds.

After a public meeting in November 2013, EPD collected and analyzed soil and groundwater samples from residences around the CSX facility. No contamination was detected in those samples above a health-based standard, Brown says. The results of that investigation were presented to the community at a public meeting in May 2014. Since the public hearing, EPD has not conducted any independent testing in the area.

“We’re scientists and not medical doctors,’’ Brown says. “For that, we rely on the expertise of the Georgia Department of Public Health.”

Behind the numbers

Ware County, which sits on the Florida line, is Georgia’s biggest county by area. But it’s not very densely populated, because large portions of it lie within the wilderness of the Okefenokee Swamp.

Waycross, the county seat and largest city, gets its name from its history as a major railroad hub. Rail lines from six directions meet in the city, so it’s literally a place where “ways cross.’’

Visitors are reminded of the railroad influence on the town as they hear the intermittent sounds of train horns. The CSX Railyard covers about 850 acres in the city, and can repair, refuel, inspect and paint cars and locomotives.

In addition to the railroad tracks, there are canals, or drainage ditches, running through much of low-lying Waycross.

According to the overall hospital discharges on Public Health’s Oasis database, Ware has a much higher level of cancer than the state average for counties from 1999 to 2013. Those data, state officials note, represent both new diagnoses and ongoing cases.

But Public Health says a more accurate indicator is the Georgia Comprehensive Cancer Registry, which found that from 2008 to 2012, Ware County’s cancer rate was below the state average. The registry reflects only new cases.

Yet even using that registry, Public Health noted in a 2014 report on Seven Out that the overall childhood cancer incidence rate for Ware County is significantly higher than the state rate.

“Ware County seems to have an elevated number of newly diagnosed lymphoma cases among children,’’ the report said. “There were six lymphoma cases during this time period [2001 – 2010], whereas about two cases would be likely. These cases were spread evenly over the 10-year period and were not geographically clustered, leading to a conclusion that this increase is likely due to chance rather than a specific cause.”

Meanwhile, the latest County Health Rankings show Ware has higher infant mortality and child mortality rates than Georgia’s averages.

Public Health, in its Seven Out report, noted that people can be exposed to contaminants through ingesting soil and food, drinking water, inhaling vapors and dust, and by skin contact.

Because their organs are still developing, infants and children are usually more susceptible to toxic substances than are adults, Public Health noted.

Children are also more likely to be exposed because they play outdoors and often take food into contaminated areas and eat it there. Because of their smaller stature, they are also more likely to encounter dust, soil, and contaminated vapors close to the ground.

Cancer clusters are real, but they are also notoriously difficult to identify. In a true cluster, according to the CDC, a greater-than-expected number of cancer cases must hit within a specific period of time. Each case must either be the same type, or derived from the same cause.

One problem with establishing direct causation is that cancer is all too common. As the CDC points out, it is the second-leading cause of death in the United States. Nationwide, one out of four deaths are due to some type of cancer.

Banding together to help

The nonprofit Mattie’s Mission, along with the family’s church, is helping Lexi’s parents with utility bills and other expenses. “It’s such a blessing,’’ says Cristy Rice.

GiGi Goble is a leader of Mattie’s Mission, which is named for her niece, who died two years ago at age 6 in Ware County from an inoperable brain tumor.

Goble notes the financial and emotional stress that hits families whose kids have cancer. The nonprofit has raised and distributed $25,000 that has gone to families and research this year.

She credits the advocacy of Joan Tibor, 54, who has collected much of the community’s data about cancer and other diseases in Waycross, and reports of the industrial site contamination.

Tibor, who lived in Waycross and the surrounding areas for more than 30 years, began having multiple health problems in the 1980s. She says she was diagnosed with lupus and rheumatoid arthritis. More recently, a physician told her she had “toxic poisoning.”

In July, Tibor had a benign tumor removed from her leg. She says she has anaphylactic reactions to certain chemicals.

She attributes her health problems to environmental contamination in and around Ware County.

Tibor contributes to a website on the situation, silentdisaster.org, and helped spur community meetings that brought in the EPA, Georgia’s EPD, and Public Health. She has also connected with Janet McMahan of Ocilla, who has pushed for South Georgia residents to test their well water for arsenic and other contamination.

“Joan has taken the bull by its horns,’’ Goble says.

Tibor and Goble have developed a list 16 of children in Ware and Pierce counties who have been diagnosed with cancers since 2011.

“We’d love for something to be done, to prove if there’s a [relationship],” Goble says.

People want an answer

One of the children with sarcoma lives in Brantley County, which is adjacent to Ware.

Ellen Walker says her grandson Gage, 5, was diagnosed with rhabdomyosarcoma recently.

Gage is receiving chemo now. The cancer was “in his belly, at the bottom of his stomach,’’ Walker says. Doctors removed Gage’s tumor in July.

“The doctor says everything is looking good,” says Walker, who is the legal guardian of Gage and another grandson. His parents live in Waycross.

Walker says she has “no idea’’ what has been causing the cancers. “Whatever it is, we need to get rid of it.”

Cristy Rice is equally befuddled. Watching as her visibly weak daughter sits in a recliner, watching TV and eating soup, Rice says, “To be honest, I don’t know what caused it. I want to know.’’

During her ordeal, Lexi has lost more than 20 pounds, Rice says.

The fact that other children have a rare cancer “is mind-blowing to me,’’ Rice says. “It’s outrageous. I want people to be held responsible for this.”

Some community members say they would like a comprehensive study of the illnesses in Ware and surrounding counties.

“We’ve not had answers on the water in the canals. I don’t think it’s been tested adequately,’’ says Ashby Nix, who as the Satilla Riverkeeper is leader of an environmental group. “We do have concerns about the potential exposure to what we know are these industrial sites. Much like the community, we have questions we’d like answered.”

Barry Tonning, an environmental planner in Kentucky who grew up in Ware County, says, “There have been a number of documented spills from Atlanta Gas Light, Seven Out and CSX.” Some occurred before federal environmental regulations were established, he adds.

Tonning’s mother, who lived in Ware County, had breast cancer. While there have been studies on individual spills, Tonning says, “I’m not aware of any broad epidemiological or groundwater study in Ware County.”

Herbert Barber, who runs Xicon Economics in Savannah, grew up in Pierce County, next to Ware. He’s doing a statistical analysis of cancer in the area “as a concerned citizen”

“There is an increase in Ware County in childhood cancer rates since 2010,’’ Barber says. “This is a serious issue that the state of Georgia should take more seriously.”

But he adds: “It’s not isolated to Ware and Pierce counties.”

A faith-based fundraiser

A fundraiser for Lexi was held recently at a Waycross restaurant. Attendees wore T-shirts that said “Philippians 4:13,” referring to a Bible verse about strength through Christian faith. The event raised hundreds of dollars.

Mandy Inman, who helped run the fundraiser, says of the childhood cancers, “It does make you wonder.”

Other residents are suspicious as well.

James and Melinda Thomas live near the CSX plant, across the street from a canal.

Melinda has had two operations for brain tumors, which were benign. James shows a reporter an analysis of her home’s tap water, and it shows a high level of TPH — total petroleum hydrocarbons.

(Some TPH compounds can affect the central nervous system, according to ATSDR. The International Agency for Research on Cancer has determined that one TPH compound, benzene, is carcinogenic to humans, and it says that also may be true of two others: benzo[a]pyrene and gasoline.)

Nihlia Griffin, 50, who grew up in Waycross and works in the city at the Georgia Partnership for Telehealth, got breast cancer in 2007. She says she had no genetic or family history of the disease.

Griffin received a double mastectomy. But with that aggressive cancer behind her, she says she now has a spot on her cervix. Doctors are “watching it,” she says.

A local health care worker, 28, who asked to be identified only as S, says she is having major fatigue, joint and nerve pain. A test for formaldehyde in her Pierce County home showed high levels, says S, who grew up in Waycross. Her two children are often sick, and her husband, 27, is experiencing heart problems.

Public Health officials say they will follow the evidence but cannot rush to judgment.

“Our goal is to protect Georgia’s population and do the most thorough investigation possible,’’ Rustin says. “These investigations do take time.”