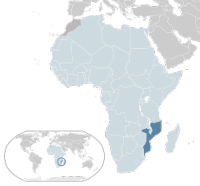

Mozambique, like many African countries, suffers from an array of health care problems.

Life expectancy there is just 50 years old. The adult HIV rate is 11 percent.

And, like many African nations, Mozambique has a shortage of skilled health care workers.

The World Health Organization recommends 235 health care workers per 100,000 population. Mozambique in 2012 had 75 workers per 100,000.

It’s that shortage that three Atlanta area organizations have teamed up to address.

The Task Force for Global Health, the CDC and a group of Georgia Tech students have produced a new Excel-based tool that can help a nation distribute health care workers more evenly around a country — ensuring that the sickest people have access to care.

The tool was developed for Mozambique, where it will be piloted this year.

The project began when CDC’s Division of Global HIV/AIDS asked a Task Force for Global Health unit to analyze the Mozambique worker gaps.

The project aims to help Mozambique “optimize their resources,’’ says Vivian Singletary, director of the Public Health Informatics Institute (PHII) requirements lab at the Task Force for Global Health, located in Decatur.

Adds Dave Ross, a Task Force vice president and director of the PHII: “How do you decide where you put the doctors or nurses? You can do it by the seat of the pants, or do it in a more methodical way.”

To develop an analytic model, the Task Force hooked up with an industrial engineering design class at Georgia Tech.

A Ph.D student there, Monica Villarreal, was among those who helped develop the tool. “It was very exciting for me to be part of this project,’’ she says, “something that had an impact, improving the lives of people.”

Task Force officials visited Mozambique last year. “They embraced the tool and asked for additional enhancements,” says Singletary, director of the Task Force’s Public Health Informatics Institute requirements lab.

The program takes into account the workers’ preferences and also the needs of each region, she adds. “It tries to balance the need and [worker] desires,” Singletary says. “It’s not always a perfect fit.”

It won’t solve the shortage of doctors, nurses and other health staff in Mozambique, though the country recently has produced more workers.

But the tool will help address gaps in services, assigning more people to work at facilities with the greatest needs.

The tool is applicable to any country that has health care worker shortages, says Ross, director of the Public Health Informatics Institute at the Task Force. “We want to have the biggest impact on HIV rates.”

Excel was used for the tool to ensure that developing countries can use it even if they only have basic computer equipment available.

Tanzania may be next to use it, Singletary says.