Probably the biggest ethical dilemma now confronting the health care world involves two expensive new drugs to treat hepatitis C.

The issue boils down to a tradeoff between efficacy and cost.

One drug, Sovaldi, has a 90 percent cure rate for newly infected patients – much better than previously available treatments for hepatitis C. It also costs $84,000 for a 12-week treatment – basically $1,000 per day.

The second drug, Olysio, is about $66,000 for a 12-week treatment, but is approved for fewer types of patients.

Some patients face even longer treatment periods – and higher costs.

Georgia Medicaid covers the drugs, though with some restrictions, for its 1.6 million beneficiaries. In March, Georgia’s Drug Utilization Review Board recommended that Medicaid add Sovaldi and Olysio as “non-preferred,” and needing a state approval in each case.

In April, 107 Medicaid patients were taking Sovaldi, at a cost of roughly $3 million per month to the program, though the state will receive a rebate that will lower that cost.

Still, physicians say the use of these two drugs is a breakthrough. “It really transformed treatment for hepatitis C,’’ Dr. Anjana Pillai, an Emory transplant hepatologist, told GHN on Tuesday.

Many silent infections

Other states’ Medicaid programs, as well as private insurers, are wrestling with the cost problem.

Julie Appleby of Kaiser Health News reported this week that if all 3 million Americans estimated to be infected with the virus are treated at an average cost of $100,000 each, the amount the U.S. spends on prescription drugs will double, from about $300 billion in one year to more than $600 billion.

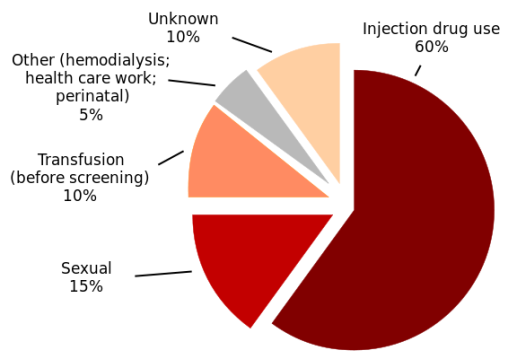

Hepatitis C is a contagious liver disease that ranges in severity from a mild illness lasting a few weeks to a serious, lifelong illness. The hepatitis C virus is spread primarily through contact with the blood of an infected person.

Most Americans with hepatitis C don’t know they have it, because they haven’t noticed any symptoms. Public health officials have been urging baby boomers (people from about 50 to their late 60s) to be tested.

Medicaid managed care plans, meanwhile, are worried about the cost. These health plans say up to 30 percent of those infected with the disease are in Medicaid.

“These are, at their core, ethical fights,” Arthur Caplan, director of the division of bioethics at New York University Langone Medical Center, told Kaiser Health News.

“The more definitive the cure, the closer we are to asking, ‘What’s the value of a human life?’ ” added Tony Keck, director of Medicaid in South Carolina, where the treatments are being covered case by case.

Jeff Myers, president and chief executive of the Medicaid Health Plans of America, told the Washington Post that the Sovaldi issue has been especially challenging because it’s an expensive specialty drug that has the potential to reach a large population of beneficiaries.

Myers’ organization wrote an April 28 letter to the National Association of Medicaid Directors, asking them to form a work group to tackle the problem. The health plan group includes as members the three managed care plans that cover most Medicaid members in Georgia.

Price ‘fair,’ says maker

There’s no doubt the drugs are highly profitable.

Gilead Sciences, the maker of Sovaldi, said it sold $2.3 billion worth of the drug in its first full quarter since FDA approval in December.

The company defends its pricing, saying the treatments are curative, and can prevent the need for other costly care, such as liver transplants.

“Gilead believes that the price of Sovaldi is fair based on the value it represents to a larger number of patients,” Gilead spokeswoman Michele Rest told Kaiser Health News.

Medicaid agencies in Louisiana, California, Michigan and Florida have limited access to the drug based on case-by-case determinations, Modern Healthcare reported.

Georgia Medicaid has approved about 75 percent of the applications for the drugs, said Linda Wiant, Medicaid pharmacy director. She said about 4,600 Medicaid beneficiaries in the state have the disease, though some may not have symptoms yet.

New drugs for the disease are expected to debut this year, potentially with shorter treatment periods, she said.

“There are physicians waiting till the new [drugs] come out toward the end of the year,’’ Wiant said.

Wiant acknowledged the cost burden. “It’s an area where we don’t control the retail price.”

And the cost of the new hepatitis C drugs is being discussed among employers and health plans, and by people having to face co-pays, Wiant added.

The number of such specialty drugs will increase in the future, she said.

Concern about patients

Besides Medicaid, the cost to privately insured patients and to the prison system is expected to be substantial.

UnitedHealthcare, one of the nation’s largest insurers, said it spent $100 million on hepatitis C treatments in the first quarter of the year.

Camilla Graham, co-director of the viral hepatitis center at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center at Harvard Medical School, told Reuters, “There is probably some price point where we as a society say we can afford to treat everyone with hepatitis C, like currently we say everyone needs to be treated with HIV.”

A member of a Florida Medicaid pharmaceutical committee, Dr. Mark Hudak, said the panel was very concerned about the price, which is far higher in the United States than in any other country, Florida Health News reported.

Hudak, chair of pediatrics at the University of Florida College of Medicine-Jacksonville, said, “Nevertheless there was recognition that this could be a disease-curing, lifesaving medication in some patients.”

Dr. Pillai of Emory agrees on the effectiveness of the drugs.

She said Emory has about 200 patients taking the new drugs – and most are taking both Sovaldi and Olysio, at a cost of roughly $150,000 per treatment.

“You can’t do that without insurance,’’ Pillai said. Emory has had good success getting Medicaid and private insurance to approve the hepatitis drugs, she added.

All the Emory patients are doing well, Pillai said.

The drugs previously used had very difficult side effects, lengthy treatment periods, and much lower success rates, she said.

In Pillai’s view, the use of the new drugs is a big improvement.

“Would I like it to be cheaper? Of course,’’ she said. But she said curing the disease can prevent billions of dollars in costs for hospitalizations, transplants, liver cancers and other complications.