Joey Krakowiak has always known he wanted to be a doctor.

Now, after four months as a medical student at the Georgia Health Sciences University-University of Georgia Medical Partnership in Athens, he is learning the basic science and clinical skills he has been curious about from an early age.

While a childhood interest in the human body may commonly lead to pursuing a career in medicine, Krakowiak didn’t initially realize just how valuable his familiarity with the Spanish language would be in his chosen profession.

“One of the largest-growing populations is the Hispanic population, so there is a huge need for doctors to be able to speak Spanish,” said Krakowiak. He is one of 40 first-year students at the Partnership, and he knows of only two others who speak Spanish.

In 2008, the American Medical Association reported that only 5 percent of the nation’s approximately 954,000 physicians were of Hispanic origin. While a particular heritage does not necessarily correspond to proficiency in a language, there’s no doubt that the percentage of Spanish-speaking patients in the nation is greater than the percentage of Spanish-speaking doctors.

Hispanics will make up 30 percent of the nation’s population by July 1, 2050, according the U.S. Census Bureau. Georgia is one of sixteen states with at least a half-million Hispanic residents, and was ranked among the 10 states with the largest Hispanic populations in 2011.

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kw4u1nqY-c8[/youtube]

History comes full circle

The Spanish language actually has a longer history in Georgia than does English. There were Spaniards in what is now the Peach State as early as 1540. But it was the British settlement of 1733 that took root and grew, making English the dominant language. And because Georgia drew relatively few immigrants until the late 20th century, English was long the native tongue of the vast majority of Georgians.

All that has changed in the past few decades, with speakers of many languages now living here. Spanish, in particular, can be heard in all areas of the state.

As Georgia’s Hispanic population grows, so does the need for Spanish-speaking physicians who understand the culture. According to the 2009 and 2010 U.S. Census Bureau, 35 percent of Hispanics reported that they were not fluent in English. Yet few Hispanics, or Spanish-speakers like Krakowiak, attend medical school.

What’s more, “language barrier” was listed among the top reasons people don’t seek medical care, according to a 2009 study conducted by the Pew Hispanic Research Center.

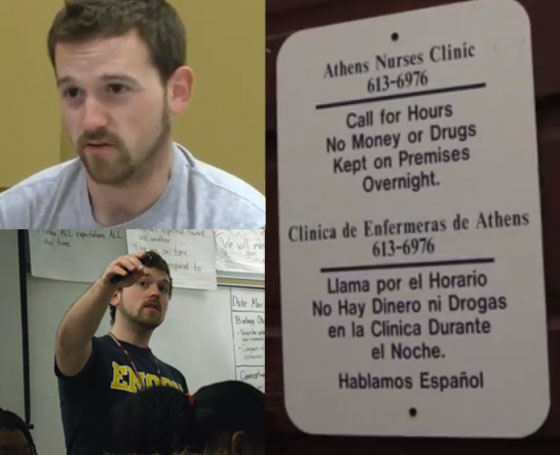

The need for Spanish-speaking health professionals and translators is acute at the Athens Nurses Clinic, where almost 11 percent of Clarke County residents are of Latino origin. The clinic provides free health and dental care to poor, uninsured patients in Athens-Clarke County and surrounding areas.

“If the health care professional doesn’t speak Spanish and the client doesn’t speak enough English, you have no idea what’s wrong with them so you can’t treat the problem,” said Paige M. Cummings, executive director of Athens Nurses Clinic. “It’s all guesswork.”

Language barriers can compromise the quality of care, leading to medical errors or medication misuse because of poor communication.

“It’s critical because when you’re thinking about health, you’re thinking about life-or-death situations,” said Irma Walker, program coordinator for Hispanic Health Coalition of Georgia, a nonprofit organization that offers education and advocacy on health issues affecting Hispanic people.

Sensitivity, professional translation are key

Language isn’t the only hurdle. A health care provider who speaks Spanish but doesn’t understand a patient’s culture may be little better off than one who speaks only English. Different customs and traditions, including eating habits, can cause miscommunication about necessary lifestyle changes or the significance of a diagnosis, especially when a word-for-word translation does not convey the real meaning.

“We can share and educate on the options, but we have to also keep in mind that there are cultural and religious beliefs that may not change,” Walker said.

Cummings said the Athens Nurses Clinic has a part-time translator, and Spanish-speaking patients are scheduled only when she is on duty.

A doctor and patient need to be able to communicate candidly, Cummings said, so it’s highly preferable not to have a patient’s relative or friend do the translating. “In order to be sure you’re getting the right story, you have to have someone who can speak that language but from whom the patient will have no need to hide the cause,” she said.

Krakowiak, who minored in Spanish in college and studied abroad in Spain, does not characterize himself as fluent in the language. But he knows enough to communicate with patients, which will also communicate an interest in them and a sensitivity to their culture.

It’s not about learning a language perfectly, Walker says, but more about being culturally sensitive. “The more sensitive we all are to each other’s differences, the better we are able to serve and understand.”

Lacey Avery is an independent journalist and graduate student at the University of Georgia pursuing health and medical journalism. Avery also works with Georgia Sea Grant, a program that promotes research, education and outreach on the Georgia coast; additional work can be found at laceyavery.weebly.com.