Story provided by Public Health News Bureau – When Farhad Jameel, case manager at Gwinnett County’s tuberculosis control clinic, arrives at work each morning, he collects his surgical mask and several large, resealable plastic bags, the kind normally used to store food. The bags contain the individual medications for four to six homebound tuberculosis (TB) patients living in the county.

He will spend the next three hours driving around the county to watch patients take their medications.

Each day, Jameel sees a handful of patients who take medications only a few days per week, plus a few others who are taking medications every day, either because their TB was only recently diagnosed or because they cannot tolerate the larger doses required for skipping days.

State law requires health officials to ensure that tuberculosis medications are taken properly and that multi-drug-resistant TB doesn’t develop. But Jameel should not have to be doing this. He’s a case manager, and it’s not in his job description to watch homebound patients take their medication. That is the responsibility of a TB outreach worker.

However, since the East Metro district’s funding for an outreach worker ran out in December 2010, Jameel and his colleagues have been doing double duty – in a region whose TB rates are among the highest in the state.

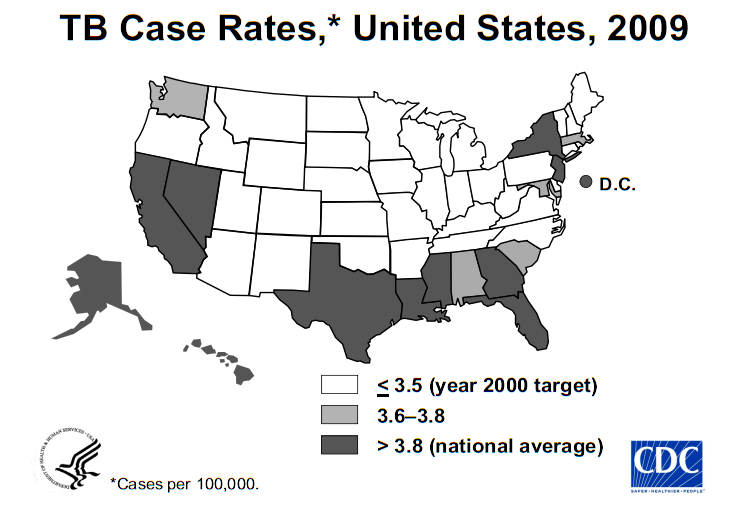

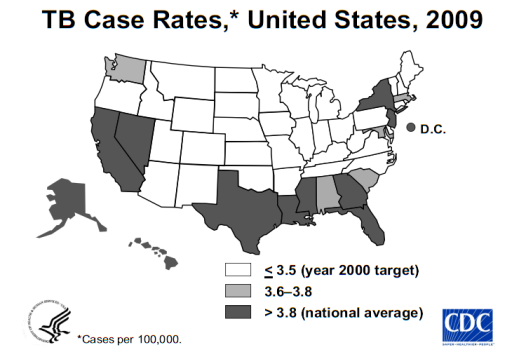

In 2010, the East Metro district, which covers Gwinnett, Newton and Rockdale counties, saw 65 new cases of TB. Fifty-six of those were in Gwinnett County, making the county second in the state for new TB cases, between DeKalb’s 86 cases and Fulton’s 51. These three counties — the state’s most populous — alternate among the top three spots each year.

“With construction and the housing boom, there were suddenly a lot more people in Gwinnett and fast,” says Donna Burel, an LPN at the tuberculosis control clinic. Since 2001, 70 percent or more of new TB patients have been foreign-born residents of the county. The October 2008 Georgia Epidemiology Report cited Gwinnett’s booming population and high concentration of immigrants from countries in which TB is endemic as the major hurdles to eliminating the infection in the county.

TB is highly contagious and must be tightly controlled by state and local public health authorities.

So Jameel can spend half his day doing outreach. Because of that, his maximum caseload was cut from 15 to seven. His colleagues, who are especially bombarded with new cases in the spring and summer, had to take over some of his cases.

As the district’s only outreach worker, Jameel feels the burden. “I think each county needs two to three outreach workers just to do DOT [direct observe therapy],” Jameel says. In fact, according to CDC recommendations, counties with TB rates like Gwinnett’s need 4.3 full-time outreach workers to administer medications and conduct contact investigations.

Many patients, few staffers

Jameel’s half-days spent on the road mean Gwinnett has half an outreach worker. For Gwinnett’s caseload, the CDC recommends a total of 13 full-time TB staffers. Gwinnett officially has 10.3; one staffer is on loan from the district office and could be taken away at any time.

“Funding and staffing depend on how many patients you have in your county, but with the recent economic crisis, we are not meeting those funding and staff requirements,” says Jameel.

Conversely, if TB rates go down in a given county, the state will assume the county can do with less funding for prevention and control. Michael Redmond, a registered nurse and the East Metro district’s tuberculosis control program manager, says that when this happened in New York state in the 1980s, there was an immediate upswing in TB cases.

TB disease is the result of infection with tuberculosis bacteria. Most infections become the noncontagious and asymptomatic latent TB (LTBI). One in ten cases of LTBI converts to the contagious, symptomatic active TB disease. Stress, poor nutrition, an immune system compromised by other illnesses, or a number of other risk factors can cause the conversion to active TB. So LTBI must be identified and treated in order to prevent this conversion and the further spread of disease.

Typically affecting the lungs, TB can infect any part of the body, such as the spine, the joints, the eye or the brain. Pulmonary TB, passed through the air via coughing, sneezing or similar actions, is the most contagious form. But all forms, if untreated, can be fatal.

According to state law, when a patient is diagnosed with TB or suspected of having TB, his or her health care provider must report it to the health department in the patient’s county. The health department then takes over the case, administering medication in person daily, monitoring the patient monthly for up to 12 months, and investigating the patient’s contacts to identify any other cases of TB or LTBI.

“For active TB patients, every dose every day must be observed by a TB worker,” Jameel says. Children under the age of 5, whether they have active disease or latent infection, must take their medication in front of a health professional each day.

This means most of the county’s active TB patients — 27 as of the end of June — report to the health department daily or several times a week to take up to five drugs needed to treat the disease, while children may take medications under the supervision of a school nurse. In part because the poor and the elderly are particularly susceptible to TB, some patients are homebound.

Jameel has driven more than 10,000 miles in a quarter on his DOT route. Stopping at houses in Lawrenceville, Snellville, Norcross and elsewhere, he dons a surgical mask before knocking on the doors of contagious patients, typically those in the first two to four weeks of their treatment. At some homes, he is in and out in a just a few minutes. At others, he stays to answer questions about symptoms or side effects the patient may be experiencing. In some homes, spouses, siblings or children of the patient may be undergoing treatment for LTBI themselves.

Medical sleuthing is essential

Some of Jameel’s time – and that of other TB workers – is spent conducting contact investigations, trying to reach and screen anyone who had contact with a TB patient during active infection.

“We need staff and time to conduct contact investigations and go out and screen people, but if caseloads go up, we’ll have just enough time to address active patients,” said Redmond.

Each time a new case is identified, case managers initiate contact investigations to discover who may be at risk of having contracted the disease from the new patient. Contact investigations could be limited to just the immediate family or they could include all of a patient’s co-workers, classmates or fellow church members.

The extent of the investigation depends on the patient’s lifestyle, and the more complicated investigations can take months to complete. Contact investigations are crucial to containing the infection.

In June, there were 11 investigations under way, 10 of them for patients in the district and one for a patient elsewhere. Gwinnett County may contribute to investigations in other districts or even other states if the patient is suspected to have had contacts in the county while contagious.

Once he’s back at the clinic, Jameel gets back to his cases. Case managers are responsible for all active cases of TB. A case can remain active for up to 12 months after diagnosis. Clinic nurses handle the latent TB patients, who continue to come to the clinic for monthly evaluations until they are free of infection.

As of June, in addition to its 27 active patients, the clinic was seeing 118 latent patients, and one multi-drug-resistant patient.

Regardless of whether a patient has a private doctor, case managers follow active TB patients from the time their disease is reported to the health department until they no longer have active TB.

“One of the hugest obstacles is to help a new patient understand that directly observed therapy is something that works for you, not something that’s being imposed on you. It’s not just because there is a trust issue, but to make sure these pills are doing what they are supposed to do for you,” said April Garcia, one of the clinic’s four case managers.

‘A lot of social work’

Patients’ treatment initially involves taking four drugs. Lab work – coordinated by the case manager and conducted on site – is regularly done to determine which medications the patient is responding to. That determination is typically made in about two months. Then the patient is taken off two of the drugs.

TB drugs can have serious side effects, including liver damage. Patients’ liver function is monitored in the on-site lab at the Gwinnett clinic. If a patient’s liver reacts to the drugs, the patient is taken off all drugs until the liver normalizes, then each drug is gradually reintroduced or second-line drugs are used. This extends the treatment time, and thus the time the patient is considered active.

In addition to monitoring patients’ sensitivity to the drugs, case managers follow the patients’ weight to make sure the involuntary weight loss associated with TB has stopped. Regular sputum tests conducted at the clinic determine if patients are still contagious.

Garcia says the role extends beyond clinical functions. She has helped patients find housing, and she has also helped them find affordable taxi service when they need transportation to the clinic.

“It’s a lot of social work,” she says.

Georgia’s regulations for the treatment and control of TB are similar to those in other states, and they’re in accordance with CDC recommendations. Without strict monitoring of treatment, the risk is too great for the spread of TB and the development of multi-drug-resistant strains, which can spread as well.

“A contagious infectious disease is a public issue,” Jameel says. “When you have a contagious disease, it’s not just the problem of the patient himself; it also becomes the problem of the people around him.”

About the Public Health News Bureau: Staffed by graduate students from the health and medical journalism concentration in the University of Georgia’s Grady College of Journalism, the Public Health News Bureau project is funded by the Healthcare Georgia Foundation and provides information about the state’s public health system that is distributed to Georgia’s news media and the public via the Partner Up! For Public Health advocacy campaign.